I first read about the KonMari method several years ago in Marie Kondo’s book on the art of tidying up. Billed as a Japanese Super Organizer, she is the demure personification of my OCD compulsions, one who recently became a global phenomenon to non-readers when her Netflix show Tidying up with Marie Kondo went viral.

I don’t think of myself as a necessarily messy person, mainly because my apartment is the size of a teaspoon and there are only so many coffee mugs you can keep on shelves as “Objets d’art” before a reality television crew calls you a hoarder. But thought not messy, I love the act of purging belongings every few years. The catharsis of getting rid of possessions has a very real effect on the state of your surroundings and by extension, the state of you.

The state of me had reached slightly nuclear proportions two years ago: my cupboards full of unworn clothes and my shelves stocked with unnecessary receipts – so it was a fortuitous time to come across Kondo. Her KonMari method says that you are not deciding what to get rid of, but rather what to keep. This saves you the trauma of trying to see if a lovely but useless item belongs in the trash, but all you should ask yourself is: does this spark joy?

Kondo is big on sparking joy. It is the currency of her whole method, so that at the end all you’re left with is clothes you really love, shoes that make you happy, documents that you really need. A spare but joyful life. Everything else isn’t trash, per se – it’s just not joyful and so doesn’t belong with you anymore. The catch is that you cannot just scan a drawer to see what makes you giddy. You must pick up each item, consider it and then decide what stays and what goes. Once you’ve decided what to keep, you find a home for each possession, and ride that wave of organizational enlightenment to a celestial state of omni-tidiness – one where everything in your life clicks into tidy place.

She has a strict schedule on how to tackle items, in decreasing order of disposability: clothes, books, papers/documents, komono i.e. miscellaneous, and finally mementos.

My biggest problem was clothes. Kondo says objects are alive in a sense, a statement I didn’t disbelieve. I have an adversarial relationship with my closet, which is roughly divided amongst friends and foes, an ever changing list of what makes me look fat or not. In confronting the old shirts that no longer fit, her suggestion that I thank them for their service made me feel all sorts of things. I was mostly at ease for being both heavier than I was when I needed them and OK that this was the case. This got easier with the pants that were too loose, which sparked joy every time I flung them into the “donate” pile. But the exercise was more emotionally taxing than I had thought. It’s built to remind you that it’s not the possessions that you’re hoarding, it’s the memories. The reason you have that hoodie from college is not because it looks great, but because it represents something to you that you don’t want to let go. Acknowledging that emotional debt makes it easier to let it go without the fear of losing the memory with it.

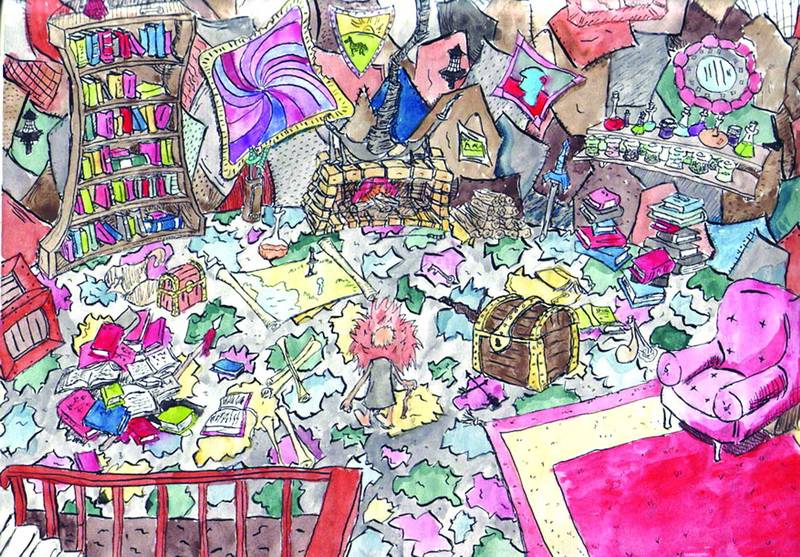

I tend to keep books, but even I had to admit that the college textbooks and cheap airport novels I had picked up over the year weren’t sparking joy. Documents were tricky because even I didn’t know why I was holding onto receipts from a Nando’s lunch from 2007. Much more difficult, though, was dreaded komono. I have way too much komono. Phantom plugs, old wires, defunct chargers, errant nail clippers, broken brushes, empty shoe boxes, used hotel key cards, old credit card statements, single socks, dried pens, broken pencils, unused calendars, bent safety pins, useless badges, apple stickers, a single chopstick, the list is as long as my drawers are full. Marie says you have to put everything into one pile, I suspect as a low-key shame tactic to get you to see how messy your secrets really are. It really works. Getting rid of most of that stuff - far more likely to spark a fire than joy - was the easiest part for me.

Next was mementos, things that hold sentimental value for you. These could be photos, old scarves, really anything that makes you feel weepy. Being an unsentimental person, I have always kept everything I hold dearest in a single shoe box. It doesn’t hold much: some old pictures, letters, a ticket stub, a tourist map, things like that. This was the only time I didn’t need Marie, because like her I believe that by the time you’re 105, three photos are more than enough as long as they make you look attractive.

The process was emotionally draining, because it’s not simple decluttering. By saying ‘thank you’ and ‘goodbye’ to each item, it brings life to the secret drawers we all hide in ourselves, the ones stuffed with resentments, grudges, hurts, joys and love. You may feel like a hippie the first time you whisper ‘thank you’ into a pair of suede trimmed jeans from 2002, but believe me, it helps.

By the end I had five suitcases of clothes to donate, three bags of paper to recycle, and a large black trash bag of things I didn’t know what to with. I let them all go joyfully , without fear that one day I’ll wake up and say “I made a huge mistake getting rid of those motorcycle boots” because a) we had the chance to say goodbye and b) getting rid of motorcycle boots is never a bad idea.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

I don’t think of myself as a necessarily messy person, mainly because my apartment is the size of a teaspoon and there are only so many coffee mugs you can keep on shelves as “Objets d’art” before a reality television crew calls you a hoarder. But thought not messy, I love the act of purging belongings every few years. The catharsis of getting rid of possessions has a very real effect on the state of your surroundings and by extension, the state of you.

The state of me had reached slightly nuclear proportions two years ago: my cupboards full of unworn clothes and my shelves stocked with unnecessary receipts – so it was a fortuitous time to come across Kondo. Her KonMari method says that you are not deciding what to get rid of, but rather what to keep. This saves you the trauma of trying to see if a lovely but useless item belongs in the trash, but all you should ask yourself is: does this spark joy?

Kondo is big on sparking joy. It is the currency of her whole method, so that at the end all you’re left with is clothes you really love, shoes that make you happy, documents that you really need. A spare but joyful life. Everything else isn’t trash, per se – it’s just not joyful and so doesn’t belong with you anymore. The catch is that you cannot just scan a drawer to see what makes you giddy. You must pick up each item, consider it and then decide what stays and what goes. Once you’ve decided what to keep, you find a home for each possession, and ride that wave of organizational enlightenment to a celestial state of omni-tidiness – one where everything in your life clicks into tidy place.

The reason you have that hoodie from college is not because it looks great, but because it represents something to you that you don’t want to let go. Acknowledging that emotional debt makes it easier to let it go without the fear of losing the memory with it

She has a strict schedule on how to tackle items, in decreasing order of disposability: clothes, books, papers/documents, komono i.e. miscellaneous, and finally mementos.

My biggest problem was clothes. Kondo says objects are alive in a sense, a statement I didn’t disbelieve. I have an adversarial relationship with my closet, which is roughly divided amongst friends and foes, an ever changing list of what makes me look fat or not. In confronting the old shirts that no longer fit, her suggestion that I thank them for their service made me feel all sorts of things. I was mostly at ease for being both heavier than I was when I needed them and OK that this was the case. This got easier with the pants that were too loose, which sparked joy every time I flung them into the “donate” pile. But the exercise was more emotionally taxing than I had thought. It’s built to remind you that it’s not the possessions that you’re hoarding, it’s the memories. The reason you have that hoodie from college is not because it looks great, but because it represents something to you that you don’t want to let go. Acknowledging that emotional debt makes it easier to let it go without the fear of losing the memory with it.

I tend to keep books, but even I had to admit that the college textbooks and cheap airport novels I had picked up over the year weren’t sparking joy. Documents were tricky because even I didn’t know why I was holding onto receipts from a Nando’s lunch from 2007. Much more difficult, though, was dreaded komono. I have way too much komono. Phantom plugs, old wires, defunct chargers, errant nail clippers, broken brushes, empty shoe boxes, used hotel key cards, old credit card statements, single socks, dried pens, broken pencils, unused calendars, bent safety pins, useless badges, apple stickers, a single chopstick, the list is as long as my drawers are full. Marie says you have to put everything into one pile, I suspect as a low-key shame tactic to get you to see how messy your secrets really are. It really works. Getting rid of most of that stuff - far more likely to spark a fire than joy - was the easiest part for me.

Next was mementos, things that hold sentimental value for you. These could be photos, old scarves, really anything that makes you feel weepy. Being an unsentimental person, I have always kept everything I hold dearest in a single shoe box. It doesn’t hold much: some old pictures, letters, a ticket stub, a tourist map, things like that. This was the only time I didn’t need Marie, because like her I believe that by the time you’re 105, three photos are more than enough as long as they make you look attractive.

The process was emotionally draining, because it’s not simple decluttering. By saying ‘thank you’ and ‘goodbye’ to each item, it brings life to the secret drawers we all hide in ourselves, the ones stuffed with resentments, grudges, hurts, joys and love. You may feel like a hippie the first time you whisper ‘thank you’ into a pair of suede trimmed jeans from 2002, but believe me, it helps.

By the end I had five suitcases of clothes to donate, three bags of paper to recycle, and a large black trash bag of things I didn’t know what to with. I let them all go joyfully , without fear that one day I’ll wake up and say “I made a huge mistake getting rid of those motorcycle boots” because a) we had the chance to say goodbye and b) getting rid of motorcycle boots is never a bad idea.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com