Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for the second part

Just before I left, there was the disturbing news of the hijacking of a PIA plane. It was hijacked by youths who were diehard supporters of Bhutto and, to make matters worse, the leader of this gang of three was Tipu—the very same far-off relative (nephew as far as I could understand) of my mother whom I had met in Karachi earlier! When I heard Tipu’s name, I was worried though I had met him only briefly. Anyway, I was taken to the airport by the British Council and the plane stopped for refuelling in Damascus. On a winter day I landed at Islamabad airport and went home. There I almost broke down with relief. It was so good to be home. I gave Ahmad a tape recorder and all the others their gifts since, as usual, even in this crisis, I had bought gifts for everyone. Then I went to bed smelling the familiar smell of mother’s cooking, the familiar sounds of my country and knowing that I was not lonely. My heart stopped sinking and, though I still slept badly, I did not suffer as I had in England.

I returned to normal but my experience had made me apprehensive of my mental health. I now felt that I needed medical help. As Ahmad was a medical student, I asked him about his lecturers in psychiatry. He told me about his own professor who was the head of psychiatry in a hospital and an associate professor in that subject in the Rawalpindi Medical College. I went to him and told him that I suffered from anxiety and panic attacks. He asked me as to how I knew this. I had read so much about it that I was sure but he disagreed without, however, telling me what was wrong with me. He then gave me some medicines which I started using. I wish I had not taken those pills because very soon they made me ill. I became so depressed that I just sat on the chair and wept and did not feel like speaking at all. Again, we all hurried to the psychiatrist but he was away. His assistant doctor, however, assured Ahmad that I was suffering from a reaction of wrong drugs. His boss, despite his reputation, had given me wrong medicines. The assistant then gave me some dose of injections in my veins which sent me to sleep. When I got up, I was still agitated.

Then came the worse illness of my life. I was so agitated that I could not rest in my bed. I kept tossing and turning. I was in mental anguish imagining all kinds of fears. At night I could not sleep again. My mother was always with me and Ahmad only went to his classes in the Medical College. He dedicated himself to serving me with such devotion that I was put to shame for not having known about these character qualities in him. We also went to Major General Shoaib, an army psychiatrist. He too suggested that I had been given an overdose of the wrong drugs and gave me some medication which helped. But that June was hot and dry outside and my mind was agitated. Ahmad and Ammi would read Ibn-e-Insha and Patras Bukhari, two Urdu humourists I loved, by my bed and I would try to listen without twisting and rolling about in my bed. Ammi was distracted with worry and even Abba, who attributed all illnesses to stomach disorder, looked worried. Ahmad was the nursing attendant and people came to visit me but nobody was told what was wrong. Nobody actually knew, not even the doctors, what actually was wrong. Then, after a month, Shoaib’s medicines started working and the depression lifted and I became calm and even started sleeping. I was weak and, though I feared a relapse, the crisis was over.

Soon after this, my friend Tariq Ahsan faced the worse trauma of his life. He was arrested as an accomplice of Jamil and Saleem, both colleagues of Tariq’s at Quad-i-Azam University, who were accused of distributing pamphlets calling for a democratic Pakistan on Tariq Ahsan’s motorcycle. When the police raided their house, Aunty Ahsan actually swallowed the paper on which I had written a few lines in doggerel verse against the martial law. Also, Tariq told all his colleagues not even to mention me as one of his visitors or friends because I had passed through an illness. However, when I heard of Tariq’s predicament, I rushed to meet his parents. I also thought of meeting General Zia ul Haq. However, soon I realised that General Zia would not meet me but Ammi persuaded Ahmad to ask Zia’s daughter, who was a student in the Rawalpindi Medical College where he was studying, to plead with her father. Nothing came out of it. Shala also asked her father, General Rafi, to approach Zia but he did not as it was an exercise in futility. None of Uncle Ahsan’s bureaucratic and intellectual friends were of any help. The only one who did help was my friend Salty who, being an army officer, instructed the jailor to allow Aunty Ahsan to visit her son with me and he complied. Tariq Ahsan told me much later that though he had done his best not even to mention my name in any connection while he was being interrogated, the first persons he met when he was allowed to see visitors in the jail were his parents accompanied by myself and Shala.

In August 1981, for lack of anything better to do, I asked my parents to request Uncle Naseer to recommend me for an ad-hoc lectureship in the National Institute of Modern Languages. The head of English department, retired Lieutenant Colonel Quraishi, Naveed’s father and my head of the English department in PMA, came personally with my appointment letter and next day I joined the NIML. I settled down to a routine of teaching English. The other teachers were Rubina Kamran and Mumtaz. I believe both did not have MA degrees then. I once gave them a lecture on Chaucer because one, or both, wanted to prepare for the MA in English literature. The NIML’s director was Brigadier Khokhar, one of my father’s junior colleagues at PMA. The place was run somewhat on the lines of PMA and I did not think an educational institution should be so regimented. Indeed, I believed that an academic and a scholar should have been the head of NIML. Later I met the former director, Dr Laeeq Babri, who had a PhD in French. At that time, although I did not know Dr Babri, I thought he was the most appropriate choice for a director. Thus, I completely disagreed with my father when he said that his friend, Brigadier Naseer, had wisely got Babri removed and the army would run NIML better. My family was so pro-army that my criticism of Zia’s martial law, or even the fact that the military should not rule Pakistan and journalists should not be whipped, were red rags to the bull for them. I was articulate and argumentative and soon discussions turned to polemics on both sides. The bitterness of these arguments with my mother, Ahmad and my father – and latter in other contexts with Tayyaba and Azam – left me feeling bitter and besieged. I was told much later by Ahmad and Ammi that they contradicted me because they thought opposite views would be corrective and would reduce my anger. I was aghast at this view since anger would not have been my reaction at all had they agreed with me in the first place. For me certain facts spelled the doom of Pakistan as I knew it. These were: that Pakistan was being ruled by a right-wing military dictator who was changing the laws so that women were becoming second-rate citizens; raped women could be punished for fornication or adultery; people could take personal revenge from their opponents by accusing them of blasphemy; and religious minorities were in jeopardy. For my family it was just my way of arguing with them as they did not understand the pain I felt and the sense of foreboding which haunted me. As it happened all I had feared did come to pass but by that time I had given up hope.

One of the arguments my family had with me was about the power, political and economic clout and perquisites and privileges of military officers. While civilian officers of the elite civil service did have a lion’s share in the pie, other civilians did not. Academics, no matter how educated thy might be, made very little money. I thought it unjust and argued that, this being the case, competent people will never go into academia and we will never create new ideas. They disagreed with my basic premise that military officers were privileged. Azam and Ahmad were both junior army officers so they were very much against my view as was Musarrat (later brigadier), who was a family friend. It was fully thirty years later that they fully concurred with my view that lifelong medical care, flats and houses at subsidised rates and plots of land which could be sold at a profit were benefits. At that time, however, I must have appeared just wrong-headed, angry and resentful to them.

Meanwhile, my mother was looking around for a wife for me. If I had to return to England to complete my MA, I would have to be accompanied. Since I had always claimed that one should choose one’s own partner for life and that arranged marriages did not make sense to me, this was a comedown for me. My parents, despite being conservative Sunnis, had even reconciled to the idea that I would marry an English girl. In fact, I would tell me mother, much to her horror and my amusement, that I would first live with a girl and then both of us would decide whether we could get married or not. This she dismissed as utter nonsense but she did expect me to bring home an English wife. Now that I had arrived with, so to speak, tail firmly between my legs, she could have mocked me but refrained from doing so though Tayyaba was much amused. But she was also part of the game of selecting girls for me. Thus, some girls were seen and rejected by my parents though I myself did not mind them. One day, Mr Mohammed Ahmad, our neighbour who was a bank manager, told us about the daughter of Mr Tajuddin, the vice principal of Aitchison College, Lahore. I, Ammi and Abba went by railcar to Lahore and stayed with a friend of Abba’s. Next evening, we went for tea to the vice principal’s huge, sprawling bungalow. He was a tall, brownish–complexioned man with a kind smile which I liked. We talked of Bareilly and Pilibhit and Aligarh where Tajuddin Sahib had been my uncle Shafi Ullah’s class fellow. Abba knew of this and had called him a “good boy.” Now the “boy” was an old gentleman and Abba was even older. Then came tea and the girl who wheeled it in was fair but not beautiful. My heart sank. Later we learned that she was the maid who served in the kitchen. Apart from her the only lady who was present was the Naseema Khala. She was, we were told, the aunt (mother’s sister) of the girl whom we had come to see but who had never appeared before us. When we got up to leave, Naseema Khala said she would drop us. When we came out, she called out to a girl who had never entered the drawing room, and now seemed to be hiding away in the bushes, to join us. Then a petite girl with a delicate pretty face came and stood on one leg with supreme indifference towards me – this was Rehana called Hana at home – my future wife. I averted my eyes shyly and did not look at her again.

When we came home it appeared that everybody had liked the girl and Abba was full of the family – they were “from the ashraf,” he said. Ammi laughed about her way of standing on one leg to advertise her supreme indifference to suitors. I laughed about it. The proposal was sent and we waited. Then Uncle Tajuddin came to Pindi and stayed in a hotel. I was invited to meet the family. I went and talked to Hana’s Uncle – mother’s brother – Feroz Mamoon and Naseema Khala, Naseema Khala’s daughter Mehnaz, called Beeba, were also there. We talked a lot and Feroz Mamoon said I was very articulate and confident. When they went back, they sent word that they had agreed to the marriage proposal. However, as they say, there is many a slip between the cup and the lip so an unanticipated impediment came in the way.

If I was to marry Hana again knowing what a wonderful treasure she proved later for me, I would not take the risk of wrecking the chances of marrying her by any kind of confession at all. I would pretend to be an angel, and a healthy one at that, who had a very assured future ahead

I was invited to Lahore by her family for getting my clothes fitted and other such preparations. At night I stayed in Hana’s little room and read the Constitution of Pakistan (1973). Next evening, we went out for a coke and ice cream and there her cousin, Afraz (called Bubbu), asked her for her ice cream cone. She frowned and moved it away. I thought she was short-tempered and had such misgivings about her that by the time I reached Pindi, I was seriously contemplating wriggling out of our proposed marriage. But I was most averse to giving pain to anybody or to make her feel rejected so I thought I should write the truth about my life to her father and leave it to him to show it to her or not. I then wrote a detailed letter writing about my heterodox liberal views and the interlude of mental illness (anxiety and depression) I had passed through as well as some other wild oats I had sown. I attached my health certificates though and also wrote that if she accepted me with all my defects, I would try my best to cherish her. I meant every word I said and had resolved that if with all these self-confessed defects they still considered me worthy of her, then I would prove myself to be worthy of their trust. My parents were surprised when I told them of what I had done. I did not confide the details to them but they understood that I had made revelations which made rejection possible and also that I was backing out of the marriage for reasons which they did not understand. My father in his bitter dismay said he would swallow the bitter pill (darhi par kalak mal lenge=I will daub black colour on my [white] beard) as such a thing as not marrying a girl after her family had accepted the marriage proposal was not a gentlemanly (sharif) thing to do. However, I paid no heed to my parents though I did realise that what I was doing was not a gentlemanly thing to do. However, a bond for life with an angry person was not good for myself or her. So, despite my own misgivings, I did not do anything to change the course of events. After a day or two of this bomb shell, Uncle Tajuddin invited me to Lahore. My family thought they would only reproach me for having revealed aspects of my life after and not before they had accepted the proposal. However, in those days I looked at the world through a positive lens as, in fact, I do even now to the point of naivety. Thus, I was confident that they were not inviting me only to insult me.

So, with positive thoughts I travelled by bus – flying coaches was the name they gave to air-conditioned buses–-to Lahore. Uncle Tajuddin was quite welcoming though he did not quite approve of some of my ideas and other things. Hana seemed just as indifferent as ever. However, as we sat before the roaring fire, Hana sent me sweet tamarind. I looked at her and my eyes looked into a pair of mischievous brown eyes which she averted immediately. I ate the tamarind, something which I had never done before, and we talked of other things but not a word of marriage. Again, I was lodged in her room and this time I completed my reading of the constitution of Pakistan. I felt at ease now as all my misgivings about her had suddenly vanished. In fact, now I wanted very much to talk to her.

This wish came true the next morning as we sat in the lovely sunshine in her back garden. Uncle Tajuddin left us and went away. She was reading Camus’s The Stranger and laid the book down. She asked me a few things and I replied. Then she said that she had noted my views and that the children would be brought up according to conventional ideas of Islamic faith and social propriety. I assented with alacrity. I could have laughed at the idea of children coming from such an indifferent-looking, apparently strait-laced and completely nonchalant maiden. However, this would not do so I kept a straight face. The sun peeped out from between the foliage and I saw the light in her twinkling brown eyes. I did not want anything to prevent our marriage now. I was much relieved when Uncle Tajuddin also confirmed that the marriage was not off. Later Hana told me that she saw my letter only as an act of complete honesty. I did mention the doubts I had after the Bubbu incident and this surprised her but she did not probe much into my motives. In fact, she had made too much of a moral hero of me and I did not have the moral courage to shatter that image. What she considered an act of courage was actually an act of kindness. But, yes, it is also true that the things I wrote to her should always be confessed beforehand in all marriages but did I really have the moral greatness to do such an act? No! I know I do not. And if I was to marry Hana again knowing what a wonderful treasure she proved later for me, I would not take the risk of wrecking the chances of marrying her by any kind of confession at all. I would pretend to be an angel, and a healthy one at that, who had a very assured future ahead. Suppose she had rejected me for all my faults, I would have missed the best wife, friend and companion in the world. So, my much-vaunted honesty, I regret to say, is not the saintly virtue of honesty which many people credit me with. I myself, however, do not delude myself by assuming such virtues.

The marriage preparations were now in full swing. My parents said the exact sum of the dower (mehr) would have to be the same as that of my sister’s. Uncle Tajuddin wanted a higher amount. When I heard of this, I immediately told my parents that the amount he had suggested was the one I would accept. Just then I got an acute pain in my kidney and my parents agreed at once. They accepted Uncle Tajuddin’s terms. But he – the decent men that he was – sent a letter back saying that he accepted Abba’s figure. Later, Hana told me that my gesture was much appreciated by everybody and especially by her.

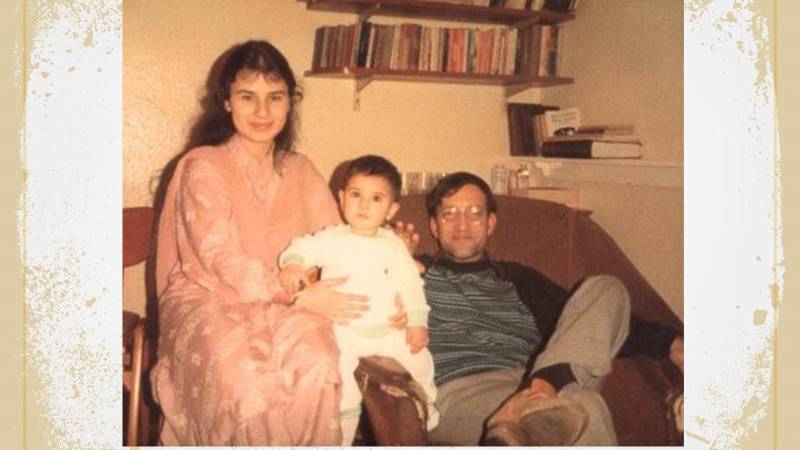

The marriage was on 18 February 1982 and that morning, soon after sunrise, we moved by cars towards Lahore. On the way we stopped at Military College Jhelum where Uncle Naseer, then the director of the Army Education Corps, had arranged an elaborate breakfast for us. We reached Lahore before midday and I sat in the principal’s house to rest and change. The principal was none other than Colonel N.D. Hassan, the father of Abid and Rashid, from our boyhood days in PMA. After sometime we went to the vice principal’s house and the maulvi sahib solemnised the marriage on the lawn of the house. After the lunch we had some tomfoolery in which I had to eat a spoonful of rice pudding. Then we went to the airport and when the Fokker took off and the air hostess announced to the passengers that they had a married couple on board, I told my wife that I already liked her. For me this was the biggest compliment I could pay. Later on, she told me that with such compliments she no longer wondered why I had had no success with women. The literal truth, it seems, is not a useful commodity in either love or war.

After a few days of songs and jokes the guests departed. I loved the songs (the tappas) which girls from the bride’s side, Beeba and Talat, sang. They were answered by songs in Urdu by our side. However, Beeba and Talat, who had been sent to keep the bride company, were more involved in eating, singing and fraternising with the enemy (girls of the groom’s side) than keeping the bride company. They were nicknamed by my mother as the dominis since dominis were used for that purpose in her family. However, these modern-day dominis did just as they pleased. But Hana was comfortable by their being around which, indeed, was their purpose. Anyway, the guests all departed and we were left on our own. Then, Ammi told me to take the car – we had a blue Suzuki van then – and go for the honeymoon. So off we went in high spirits. Our first stop was Hassan Abdal where we had fried fish. It was an emotionally heightened and happy event and I have never forgotten it. In Abbottabad my friend Salty, Major Sultan Mahmood (later brigadier), had arranged our stay in the Frontier Force Regiment’s officers’ mess. As it was cold his family sent us a heater and also invited us to their house for dinner. We went to the places I loved like Burn Hall and PMA. In the latter place we met Ashfaq and Annie who also invited us for dinner. I even ventured out towards Kala Pani. However, the narrow mountain road was blocked with snow and at one point the car started slipping down towards the abyss. I told Hana to get down but she refused. I was touched though I said this was foolish as she could help me more even if the van did go down. But the van revved itself back and we came away from the edge. I decided to give up adventures but could not bring myself to follow the straight and narrow path of caution till much later in life. Thus, when we were near Pindi I asked Hana whether she wanted to go to Murree. This was an adventure and she was delighted so we moved on to continue the idyll for yet another day.

(to be continued)