We cannot bask in the glory or ignominy of our ancestors. Those accolades and burdens are theirs to bear.

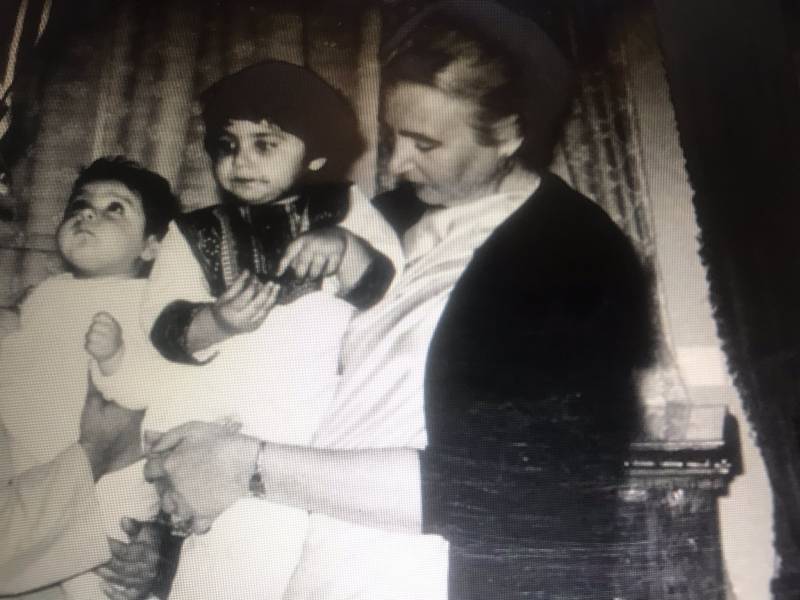

That said, my late grandmother Jennifer Musa Qazi remains a role model for my sister and I. She was born in Kerry, a county in Southern Ireland. After she married my grandfather Qazi Musa, she made her home in Pishin, Balochistan, from 1948 till her death in January 2008. She left behind a proud legacy of service.

On the Golden jubilee celebration of Pakistan’s 1973 Constitution, I write this piece, because Jennifer Musa Qazi was one of the 25 members of the Constituent Committee & Assembly that (eventually) signed the 1973 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

I grew up hearing stories about the chaos and thrill around the making of the document that encapsulates our social contract. I have remained fascinated with it, and what it stands for; perhaps also what it should stand for.

Jennifer Musa was a social democrat by political leaning. She believed in equity & fairness for all, irrespective of creed, gender, or any other distinction. These weren’t theories or platitudes, she lived by these principles in her everyday life and work. Although she married into a privileged family, that lifestyle did not endear her to extravagance or indulgence, quite the contrary. She preferred modesty in everything, we were drilled with these values and constantly reminded of standing on our own feet. Education is your wealth, hard work your status - these were her twin mantras to all of us. So many years later, the respect she is accorded in Pishin, and all those who were fortunate to have known her, is testament to her work ethic and worldview.

We are all products of our social environment and learning. Jennifer Musa experienced post World War 1 Ireland’s social economic hardships. The only way out of economic struggles was hard work. She knew what rationing of food felt like. With large families with lots of mouths to feed, the young had to become independent quickly. But no short cuts. Hard work. She was trained as a nurse before she met my grandfather and moved to Pakistan soon after it had become an independent country.

Standing on her own feet became a hallmark of hers. She was widowed very young in 1956. She chose to stay and raise her young son in Balochistan. She turned to what she knew best. Hard work.

It couldn’t have been easy living alone in Pishin, but she did and loved it. She set up the first ice factory in the province. She was involved in agriculture on the lands she inherited. She adopted local madrassas and introduced English and math to the students. Her life in Pishin was spent developing skills and finding solutions within the confines of local cultures. The Afghan war had spilled into Pishin and the refugees outnumbered the local residents for a long time; perhaps even now? Maha and I spent an enormous amount of time in the refugee camps where she worked with the women to teach them the value of income generation for themselves and lots of other life skills.

Always interested in public works, she joined the National Awami Party (NAP). It’s important to address an inaccurate assumption about Jennifer Musa also. She was not nominated to the Constitutional Committee in 1972 because she was a Qazi. She was in fact a member of NAP, a socialist party led by Sardar KB Marri and Sardar Jogazei et al. These were a different set of thinkers from the Pakistan Muslim League, of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who held quite different views from the Muslim League. NAP some would argue held fundamentally different political leaning from the Muslim League. I thought it important to state this fact once and for all. She had married into privilege, but spent her entire life dedicated in service to the people she had adopted. She carved her own political and social path, independently.

I was a toddler when Jennifer Musa was in Parliament and involved in shaping our Constitution. It was a decade or so later, when I began asking questions and paid attention to conversations around this subject. I have remained very curious about this period in our history - especially from Balochistan’s perspective. Yes, there is a provincial perspective because the Constitution has impacted citizens of Pakistan unequally.

I have sought to read the minutes of the 1973 constitutional committee many times, to better understand the recorded process of its development, but like many things in this country, it is not accessible. In fact, I have recently learned they are classified. Perhaps they have been lost or burned in the 1996 fires in the National Assembly. The audio tapes of the 1972-1973 debates on the floor, have been burnt and lost forever. The Committee Minutes probably have survived but are ‘unavailable’; even the Secretary of the National Assembly has no access to these historic documents.

Naturally, I am devastated to learned this.

The lack of respect and importance we give to precious histories is heart wrenching. The managers of the state are hell bent on erasing and manipulating what is our history and any memory of it. Nevertheless, there are three volumes of the debates on the floor of the National Assembly between the opposition and government of the time, surrounding the formation of the 1973 Constitution. These need to be studied and commented upon more frequently and discussed in light of our perpetual crisis in Pakistan.

In the absence of the detailed accounts of what was stated and debated between the 25 members formally in the Constituent Committee meetings (36 days), there remains a vast memory of knowledge around this constitution making, which is unrecorded. I have read the ‘Report of the Constituent Committee’ dated 3rd December 1972, which is a sanitized summation of the 25 members, after the draft 1973 Constitution was presented as a Bill in December 1972.

I hope other Pakistanis who have inherited information from reservoirs of memories regarding the making of the 1973 Constitution step forward and share them in print. Many of those stories need to be shared and understood, however uncomfortable and disquieting.

One of two women in the constituent committee, Jennifer Musa represented the largest province of the federating units of Pakistan - Balochistan. She was a nominee of the National Awami Party (NAP), as a member of the opposition, but led two governments in the NWFP and Balochistan. She joined the Constitutional Committee late, after her colleague on the Committee resigned in protest. The first question that comes to my mind was, why did he resign? What were the issues that forced such a drastic response? These are important matters to deliberate upon even today because those very issues continue to shape our disquiet with the center and governors of Pakistan.

I believe there were 8 demands NAP wanted incorporated in the draft Constitution in 1972. There was a Draft Constitution shared in December 1972 in the form of a Bill. The final was formalized in April of 1973. What were the clauses and ideas NAP lobbied for in 1972? What were incorporated and what were rejected and why?

I believe the following issues dominated NAP’s demands; the recognition and protecting the interests of minority ethnonational groups. The recognition of the multiethnic character of Pakistani society, and protecting languages and cultures was another. The establishment of a strong upper chamber in the federal legislature, and the adoption of a non-majoritarian framework of constitution making process, based on the equality of all four ethnonational groups from Punjab, Sindh, NWFP and Balochistan. All these demands would have ensured a more inclusive Pakistan and a broader understanding of the diversity that makes this country beautiful. Population alone could not determine the nature of our federation.

Z.A. Bhutto, the President of the time, was rigidly against devolving powers to the provinces. The hesitance to accommodate these demands had already led to NAP’s boycott of the constitution making proceedings at a time when the assembly had only approved one-third of the provisions of the draft Constitution. Out of the 400 amendments proposed by the opposition, only one was accepted during their stay in the assembly.

Which one?

The remaining two-thirds of the draft constitution was adopted in the absence of opposition members, leading to the lapse of sixteen hundred amendments moved by the opposition members in the draft constitution.

We need more information to understand this process.

It seems the Constitution making process continued, without much input from the opposition - more accurately, Balochistan and NWFP’s inputs. Once NAP realized Bhutto was happy to fashion a social contract document without the input from the federating units, they had two choices; boycott and move in a direction they had recently seen unfold or come to the table again and see what they could salvage.

For reasons I am unaware of, they chose the latter option, and nominated Jennifer Musa to join the Constituent Committee to ensure Balochistan’s voice and interests were not completely absent in the shaping of the National Framework of Principles. Too many of the opposition’s amendments and suggestions had been rejected by Z.A. Bhutto. At the core of the dispute between NAP & PPP was that Balochistan wanted the provinces that were not as populous to have a more equitable share in governing their own destiny. PPP and Mr. Bhutto did not. In 2023, the irony isn’t lost.

Bhutto controlled Punjab then, and perhaps thought he would forever. From NAP’s perspective, Balochistan was the largest province of the federation of Pakistan. It may have the smallest population but remains 44% of the country’s landmass. It is vast, rich, and bountiful. It is not a land without people. Today, 50 years on, it continues to be exploited, and its people overlooked in all Constitutional responsibilities; promises of rights, welfare, and development opportunities, all enshrined and aspired through the 1973 Constitution.

The subpar governors of Balochistan which followed are reasons for the province's malaise, but poor governance is not the only cause of Balochistan’s current disquiet with the Constitution of Pakistan and the managers of the state. No doubt, the regular interruption of formal democracy in Pakistan’s history has had a negative role in exacerbating vulnerabilities in Balochistan.

Little security in a security state

It is also important to recognize that the Constitution failed its people. First, it was Z.A. Bhutto, a civilian democratically elected Prime Minister, who invaded Balochistan, and removed an elected government from Quetta, soon after the Constitution was put into force. Bhutto faced no consequences or charges for his actions.

The 1973 Constitution was signed in April, and the ink had barely dried when Bhutto sent in the army to remove the elected government in Quetta. Disenfranchising Balochistan was first done by a PPP civilian government. The Constitution of 1973 could not, or did not protect its citizens in Balochistan.

No one was ever punished for this treasonous act. To the contrary, Pakistanis in Balochistan have not benefited from the constitutionally enshrined promises of welfare, security, and dignity since.

50 years of neglect and abuse

Zulifqar Ali Bhutto, the President of Pakistan during this period, was a devious man. He would promise and renege without blinking. The largest number of amendments to the 1973 Constitution were made immediately after it was signed, by him alone. 50 years on, it is time, when two thirds of the country’s population were born a generation after the 1973 Constitution was formulated, to take another look at the social contract’s track record.

Why is Pakistan on this perpetual cycle of self-destruction. Why are democracy and human rights not taking root? These are the questions we need to address publicly. Five decades of denial can only lead to more pain. It is time. Let us make promises we plan on keeping. Let us revisit our social contract with clean hands.

That said, my late grandmother Jennifer Musa Qazi remains a role model for my sister and I. She was born in Kerry, a county in Southern Ireland. After she married my grandfather Qazi Musa, she made her home in Pishin, Balochistan, from 1948 till her death in January 2008. She left behind a proud legacy of service.

On the Golden jubilee celebration of Pakistan’s 1973 Constitution, I write this piece, because Jennifer Musa Qazi was one of the 25 members of the Constituent Committee & Assembly that (eventually) signed the 1973 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

I grew up hearing stories about the chaos and thrill around the making of the document that encapsulates our social contract. I have remained fascinated with it, and what it stands for; perhaps also what it should stand for.

Jennifer Musa was a social democrat by political leaning. She believed in equity & fairness for all, irrespective of creed, gender, or any other distinction. These weren’t theories or platitudes, she lived by these principles in her everyday life and work. Although she married into a privileged family, that lifestyle did not endear her to extravagance or indulgence, quite the contrary. She preferred modesty in everything, we were drilled with these values and constantly reminded of standing on our own feet. Education is your wealth, hard work your status - these were her twin mantras to all of us. So many years later, the respect she is accorded in Pishin, and all those who were fortunate to have known her, is testament to her work ethic and worldview.

We are all products of our social environment and learning. Jennifer Musa experienced post World War 1 Ireland’s social economic hardships. The only way out of economic struggles was hard work. She knew what rationing of food felt like. With large families with lots of mouths to feed, the young had to become independent quickly. But no short cuts. Hard work. She was trained as a nurse before she met my grandfather and moved to Pakistan soon after it had become an independent country.

Standing on her own feet became a hallmark of hers. She was widowed very young in 1956. She chose to stay and raise her young son in Balochistan. She turned to what she knew best. Hard work.

It couldn’t have been easy living alone in Pishin, but she did and loved it. She set up the first ice factory in the province. She was involved in agriculture on the lands she inherited. She adopted local madrassas and introduced English and math to the students. Her life in Pishin was spent developing skills and finding solutions within the confines of local cultures. The Afghan war had spilled into Pishin and the refugees outnumbered the local residents for a long time; perhaps even now? Maha and I spent an enormous amount of time in the refugee camps where she worked with the women to teach them the value of income generation for themselves and lots of other life skills.

Always interested in public works, she joined the National Awami Party (NAP). It’s important to address an inaccurate assumption about Jennifer Musa also. She was not nominated to the Constitutional Committee in 1972 because she was a Qazi. She was in fact a member of NAP, a socialist party led by Sardar KB Marri and Sardar Jogazei et al. These were a different set of thinkers from the Pakistan Muslim League, of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who held quite different views from the Muslim League. NAP some would argue held fundamentally different political leaning from the Muslim League. I thought it important to state this fact once and for all. She had married into privilege, but spent her entire life dedicated in service to the people she had adopted. She carved her own political and social path, independently.

I was a toddler when Jennifer Musa was in Parliament and involved in shaping our Constitution. It was a decade or so later, when I began asking questions and paid attention to conversations around this subject. I have remained very curious about this period in our history - especially from Balochistan’s perspective. Yes, there is a provincial perspective because the Constitution has impacted citizens of Pakistan unequally.

I have sought to read the minutes of the 1973 constitutional committee many times, to better understand the recorded process of its development, but like many things in this country, it is not accessible. In fact, I have recently learned they are classified. Perhaps they have been lost or burned in the 1996 fires in the National Assembly. The audio tapes of the 1972-1973 debates on the floor, have been burnt and lost forever. The Committee Minutes probably have survived but are ‘unavailable’; even the Secretary of the National Assembly has no access to these historic documents.

Naturally, I am devastated to learned this.

The lack of respect and importance we give to precious histories is heart wrenching. The managers of the state are hell bent on erasing and manipulating what is our history and any memory of it. Nevertheless, there are three volumes of the debates on the floor of the National Assembly between the opposition and government of the time, surrounding the formation of the 1973 Constitution. These need to be studied and commented upon more frequently and discussed in light of our perpetual crisis in Pakistan.

In the absence of the detailed accounts of what was stated and debated between the 25 members formally in the Constituent Committee meetings (36 days), there remains a vast memory of knowledge around this constitution making, which is unrecorded. I have read the ‘Report of the Constituent Committee’ dated 3rd December 1972, which is a sanitized summation of the 25 members, after the draft 1973 Constitution was presented as a Bill in December 1972.

I hope other Pakistanis who have inherited information from reservoirs of memories regarding the making of the 1973 Constitution step forward and share them in print. Many of those stories need to be shared and understood, however uncomfortable and disquieting.

One of two women in the constituent committee, Jennifer Musa represented the largest province of the federating units of Pakistan - Balochistan. She was a nominee of the National Awami Party (NAP), as a member of the opposition, but led two governments in the NWFP and Balochistan. She joined the Constitutional Committee late, after her colleague on the Committee resigned in protest. The first question that comes to my mind was, why did he resign? What were the issues that forced such a drastic response? These are important matters to deliberate upon even today because those very issues continue to shape our disquiet with the center and governors of Pakistan.

I believe there were 8 demands NAP wanted incorporated in the draft Constitution in 1972. There was a Draft Constitution shared in December 1972 in the form of a Bill. The final was formalized in April of 1973. What were the clauses and ideas NAP lobbied for in 1972? What were incorporated and what were rejected and why?

I believe the following issues dominated NAP’s demands; the recognition and protecting the interests of minority ethnonational groups. The recognition of the multiethnic character of Pakistani society, and protecting languages and cultures was another. The establishment of a strong upper chamber in the federal legislature, and the adoption of a non-majoritarian framework of constitution making process, based on the equality of all four ethnonational groups from Punjab, Sindh, NWFP and Balochistan. All these demands would have ensured a more inclusive Pakistan and a broader understanding of the diversity that makes this country beautiful. Population alone could not determine the nature of our federation.

Z.A. Bhutto, the President of the time, was rigidly against devolving powers to the provinces. The hesitance to accommodate these demands had already led to NAP’s boycott of the constitution making proceedings at a time when the assembly had only approved one-third of the provisions of the draft Constitution. Out of the 400 amendments proposed by the opposition, only one was accepted during their stay in the assembly.

Which one?

The remaining two-thirds of the draft constitution was adopted in the absence of opposition members, leading to the lapse of sixteen hundred amendments moved by the opposition members in the draft constitution.

We need more information to understand this process.

It seems the Constitution making process continued, without much input from the opposition - more accurately, Balochistan and NWFP’s inputs. Once NAP realized Bhutto was happy to fashion a social contract document without the input from the federating units, they had two choices; boycott and move in a direction they had recently seen unfold or come to the table again and see what they could salvage.

For reasons I am unaware of, they chose the latter option, and nominated Jennifer Musa to join the Constituent Committee to ensure Balochistan’s voice and interests were not completely absent in the shaping of the National Framework of Principles. Too many of the opposition’s amendments and suggestions had been rejected by Z.A. Bhutto. At the core of the dispute between NAP & PPP was that Balochistan wanted the provinces that were not as populous to have a more equitable share in governing their own destiny. PPP and Mr. Bhutto did not. In 2023, the irony isn’t lost.

Bhutto controlled Punjab then, and perhaps thought he would forever. From NAP’s perspective, Balochistan was the largest province of the federation of Pakistan. It may have the smallest population but remains 44% of the country’s landmass. It is vast, rich, and bountiful. It is not a land without people. Today, 50 years on, it continues to be exploited, and its people overlooked in all Constitutional responsibilities; promises of rights, welfare, and development opportunities, all enshrined and aspired through the 1973 Constitution.

The subpar governors of Balochistan which followed are reasons for the province's malaise, but poor governance is not the only cause of Balochistan’s current disquiet with the Constitution of Pakistan and the managers of the state. No doubt, the regular interruption of formal democracy in Pakistan’s history has had a negative role in exacerbating vulnerabilities in Balochistan.

Little security in a security state

It is also important to recognize that the Constitution failed its people. First, it was Z.A. Bhutto, a civilian democratically elected Prime Minister, who invaded Balochistan, and removed an elected government from Quetta, soon after the Constitution was put into force. Bhutto faced no consequences or charges for his actions.

The 1973 Constitution was signed in April, and the ink had barely dried when Bhutto sent in the army to remove the elected government in Quetta. Disenfranchising Balochistan was first done by a PPP civilian government. The Constitution of 1973 could not, or did not protect its citizens in Balochistan.

No one was ever punished for this treasonous act. To the contrary, Pakistanis in Balochistan have not benefited from the constitutionally enshrined promises of welfare, security, and dignity since.

50 years of neglect and abuse

Zulifqar Ali Bhutto, the President of Pakistan during this period, was a devious man. He would promise and renege without blinking. The largest number of amendments to the 1973 Constitution were made immediately after it was signed, by him alone. 50 years on, it is time, when two thirds of the country’s population were born a generation after the 1973 Constitution was formulated, to take another look at the social contract’s track record.

Why is Pakistan on this perpetual cycle of self-destruction. Why are democracy and human rights not taking root? These are the questions we need to address publicly. Five decades of denial can only lead to more pain. It is time. Let us make promises we plan on keeping. Let us revisit our social contract with clean hands.