Although an unconventional read, I was surprised at the ambitions and imaginative force depicted by Shehan Karunatilaka – the float between life and death, vengeance and forgiveness, the power of journalism, political corruption in one of the most literate countries in the world, life and death, and reality and metaphysics.

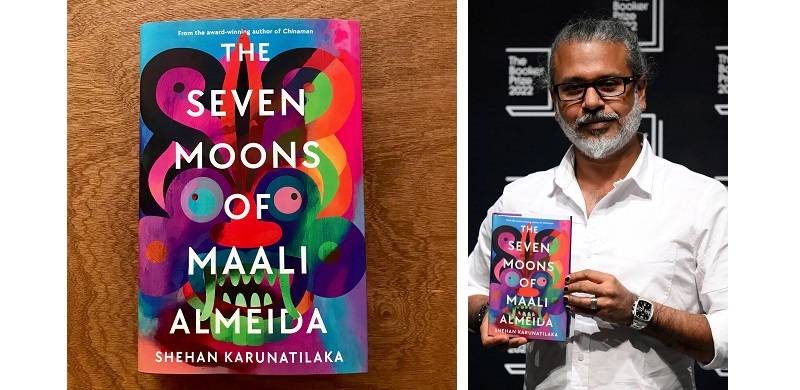

A photographer begins to bare the massacre of Sri Lanka’s civil wars in Colombo, 1990 – that is what The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is all about. The Booker win, Britain’s highest literary honour, is a story by Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka, brimming with humour and pathos, and the second win from the South Asian Subcontinent to have made the cut, the first one being Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree. A murder mystery and an unconventional comedy at heart, the book centers around the various military atrocities, an element that is quite relatable to Pakistan as well, what with all the Third World country vibes. Of course, it was all too familiar with its bureaucratic red tape and jaded workers.

A lot like Salman Rushdie who started his career in advertising, and was inspired by his own fiction, Karunatilaka has also worked with advertising, writing rock songs, screenplays and travel stories. He emerged onto the global literary stage in 2011, when he won the Commonwealth Book Prize, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, and Gratiaen Prize for his debut novel Chinaman.

Cracking the plot, the book is a narration in the second person (with a slightly distancing effect) by a dead man, Maali Almeida, a war photographer who loves his trusted Nikon camera, a gambler in high-stakes poker, and a closet queen who is an atheist. In the beginning of the book, he wakes up dead. He thinks he has swallowed some pills and is hallucinating. And he is locked in an underworld. It’s no Miltonian mayhem; for him, “the afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants their rebate.”

Other dead spirits surround him, with disjointed limbs and blood-stained clothes. They are unable to form a queue. Many of them he meets in the landscape are targets of the violence plaguing the country. One of them is a university professor who has been gunned down for speaking against the military group Tamil Tigers. There are also the victims of People’s Liberation Party, who spoke against the Sri Lankan government, along with many left-wing and working-class civilians.

A witness to the inhumanity of the uprisings in Sri Lanka, Maali is an itinerant photographer for newspapers and magazines with an ambition to “bring down governments.”

“Photos that could stop wars.”

He has captured “the government minister who looked on while the savages of 83 torched Tamil homes and slaughtered the occupants,” and taken “portraits of disappeared journalists and vanished activists, bound and gagged and dead in custody.”

All these pictures are piled beneath a bed in his family home. Now, he only has seven moons – one week – to reach out to his friend Jaki and her cousin, to discover how he died, reach out to them, and lead them to his tranche of secret photographs, to circulate them throughout Colombo, the largest city in Sri Lanka, and expose the violent conflict through them.

Maali is told that “every soul is allowed seven moons to wander the In Between. To recall past lives. And then, to forget. They want you to forget. Because, when you forget, nothing changes.”

And he doesn’t want to be another forgotten statistic. Those photos constitute his legacy, which, he believes, has the power to transform the country.

After seven moons, the door to 'The Light' – a heaven of sorts – will be closed forever.

The book dedicates one chapter to each of the seven moons, and we meet various characters and complex mythological references. Although an unconventional read, I was surprised at the ambitions and imaginative force that was depicted in it – the float between life and death, vengeance and forgiveness, the power of journalism, political corruption in one of the most literate countries in the world, life and death, and reality and metaphysics.

Some literary critics call it a dystopic satire. Others, an absurd comedy. Others still, a grotesque tragedy. For me, it is the best mix of all. It is witty, innovative, and heart-rending. Karunatilaka’s style is refreshingly free of cliché. It is a deserving winner of the Booker Prize.

And above it all, this book is not some easy fiction breeze-through. It requires time, patience, and undivided attention – unfurling, unlearning and becoming. And it is worth every minute.

A photographer begins to bare the massacre of Sri Lanka’s civil wars in Colombo, 1990 – that is what The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is all about. The Booker win, Britain’s highest literary honour, is a story by Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka, brimming with humour and pathos, and the second win from the South Asian Subcontinent to have made the cut, the first one being Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree. A murder mystery and an unconventional comedy at heart, the book centers around the various military atrocities, an element that is quite relatable to Pakistan as well, what with all the Third World country vibes. Of course, it was all too familiar with its bureaucratic red tape and jaded workers.

A lot like Salman Rushdie who started his career in advertising, and was inspired by his own fiction, Karunatilaka has also worked with advertising, writing rock songs, screenplays and travel stories. He emerged onto the global literary stage in 2011, when he won the Commonwealth Book Prize, the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, and Gratiaen Prize for his debut novel Chinaman.

Cracking the plot, the book is a narration in the second person (with a slightly distancing effect) by a dead man, Maali Almeida, a war photographer who loves his trusted Nikon camera, a gambler in high-stakes poker, and a closet queen who is an atheist. In the beginning of the book, he wakes up dead. He thinks he has swallowed some pills and is hallucinating. And he is locked in an underworld. It’s no Miltonian mayhem; for him, “the afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants their rebate.”

Other dead spirits surround him, with disjointed limbs and blood-stained clothes. They are unable to form a queue. Many of them he meets in the landscape are targets of the violence plaguing the country. One of them is a university professor who has been gunned down for speaking against the military group Tamil Tigers. There are also the victims of People’s Liberation Party, who spoke against the Sri Lankan government, along with many left-wing and working-class civilians.

A witness to the inhumanity of the uprisings in Sri Lanka, Maali is an itinerant photographer for newspapers and magazines with an ambition to “bring down governments.”

“Photos that could stop wars.”

Cracking the plot, the book is a narration in the second person (with a slightly distancing effect) by a dead man, Maali Almeida, a war photographer who loves his trusted Nikon camera, a gambler in high-stakes poker, and a closet queen who is an atheist

He has captured “the government minister who looked on while the savages of 83 torched Tamil homes and slaughtered the occupants,” and taken “portraits of disappeared journalists and vanished activists, bound and gagged and dead in custody.”

All these pictures are piled beneath a bed in his family home. Now, he only has seven moons – one week – to reach out to his friend Jaki and her cousin, to discover how he died, reach out to them, and lead them to his tranche of secret photographs, to circulate them throughout Colombo, the largest city in Sri Lanka, and expose the violent conflict through them.

Maali is told that “every soul is allowed seven moons to wander the In Between. To recall past lives. And then, to forget. They want you to forget. Because, when you forget, nothing changes.”

And he doesn’t want to be another forgotten statistic. Those photos constitute his legacy, which, he believes, has the power to transform the country.

After seven moons, the door to 'The Light' – a heaven of sorts – will be closed forever.

The book dedicates one chapter to each of the seven moons, and we meet various characters and complex mythological references. Although an unconventional read, I was surprised at the ambitions and imaginative force that was depicted in it – the float between life and death, vengeance and forgiveness, the power of journalism, political corruption in one of the most literate countries in the world, life and death, and reality and metaphysics.

Some literary critics call it a dystopic satire. Others, an absurd comedy. Others still, a grotesque tragedy. For me, it is the best mix of all. It is witty, innovative, and heart-rending. Karunatilaka’s style is refreshingly free of cliché. It is a deserving winner of the Booker Prize.

And above it all, this book is not some easy fiction breeze-through. It requires time, patience, and undivided attention – unfurling, unlearning and becoming. And it is worth every minute.