One of the inspirations for my recent move to Istanbul is the haunting lyricism of its writers, poets and artists. We were very fortunate to have the author Elif Shafak join us in a virtual women’s hour at work while live streaming from London.

For those who are not familiar with her work, she is a storyteller at heart. In a seemingly effortless way, she is able to weave narrative magic between the Istanbul of her childhood to her current life in London. She grew up with her maternal grandmother – while her mother went back to school after a divorce and qualified as a foreign diplomat. That changed the course of their lives and formed the basis for an international outlook and curious self-reflection that often comes when one steps away from one’s comfort zone.

Though naturalised as a UK citizen over time, Shafak’s affinity is with Turkey. She has lived in London since 2013, but she speaks of carrying Istanbul in her soul and reflects that “motherlands are castles made of glass. In order to leave them, you have to break something – a wall, a societal convention, a cultural norm, a psychological barrier, a heart. What you have broken will haunt you,” she writes.

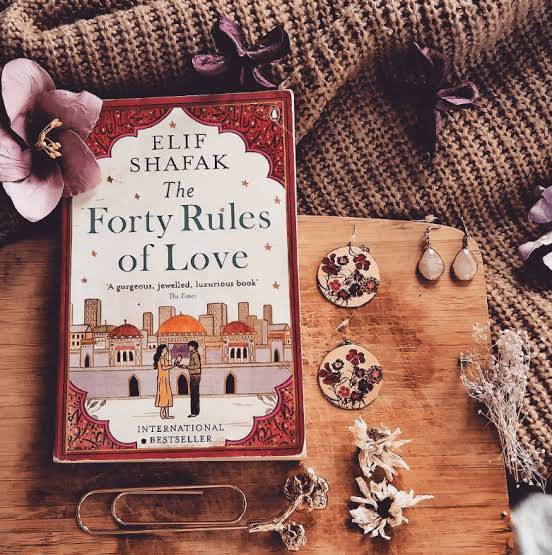

She explores such diverse subjects as Sufi mysticism and love in her Forty Rules of Love (2009), and her own post-partum depression in Black Milk (2007).

How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division (2020), a brief fifty-page treatise on her outlook on life seems to resonate these days. Many of you probably feel the same these days – how does one remain sane in a world that seems to be increasingly insane wherever you look?

It is hard to turn on the news or social media and not feel your heart break on a daily basis. Working on the Middle East brings the impact of the current crises home to me. I listen to stories from my colleagues in Jerusalem and our clients in the West Bank in Palestine. Equally poignant is the palpable unease of the Jewish community in Istanbul. Debate and dialogue seem impossible. Understanding the other side is a memory, buried in the past.

Shafak has a few lessons to share from her own experience and most profoundly, it was the sense of connection that centres her– that she looks at it in three dimensions.

The first is connection with self – and tending to her inner garden or sense of self and what gives her resilience. This involves the ability to look inward and draw strength, whether through reliance on God, mysticism or the world that cannot be seen, and what gives one sustenance each day.

Next is a connection with others, a sense of belonging to a community or whether through a sense of being to connect with others who are from different walks of life – whether income, religion, social strata – the ability to speak to them and truly connect as humans.

The third is the connection with nature – in its profound beauty whether a simple walk through a green space or time outdoors. According to her, these elements restore an optimism of hope which gives her strength to continue her storytelling journey.

Her attempt to do so is documented in her open online dialogue with others called Unmapped Storylands which is a collection of stories, anecdotes and thoughts, insights and musings centred around her personal unpublished notebooks on an open platform Substack.

As I read her musings, I think it important or perhaps even essential that one should have one’s own creative space like hers that allows her artistic and creative freedom.

Shafak has a PhD in Political Science. Therefore social issues are at the centre of what she does. She is not afraid of tackling controversial topics such as child abuse or the Armenian genocide, which prompted swift rebuke from authorities. Her non-fictional activism makes short shrift of democracy in Turkey where she is understandably less than popular with the authorities.

That did not change her sense of self or identity, which makes you think that one can carry oneself within one – in her words, “I hunt everywhere for a life worth living and a knowledge worth knowing. Having roots nowhere I have everywhere to go.”

Writers like Shafak live solitary lives in a way, removing themselves from the world in order to create magical worlds of their own, one word at a time. For her, as a woman, to do so seems even harder. Her gender is expected to comfort and be of service to others. Many women I have spoken to struggle with creativity and finding time to tend to themselves – their ‘inner gardens’ as Shafak refers to that neglected space, rather than ourselves.

One is reminded of the British novelist Virginia Woolf and her introspective essay A Room of One’s Own (1929). In it, Woolf uses metaphors to explore social injustices and comments on women's lack of free expression. Her metaphor of a fish explains her most essential point, "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction."

Shafak avoids such generalisations about gender when she speaks. In fact, she speaks about female energy and male energy – yin and yang – which exist in all of us and allow us to tap into the balance that we crave as humanity.

Her journey is an inspiration not only because they are well regarded in a literary manner but as they shed light on many socially important issues of our time – be it freedom of expression, mental health and depression, women’s empowerment and rights and political conflicts.

To do so is brave and requires an authenticity of character – a strong sense of self and self-expression. It requires a strength that though we are different, we can draw our strength from that otherness.

Without understanding one’s own stories, she argues, it is difficult to understand the stories of others, particularly those that are “systemically unheard.” Her thesis draws on channelling anger into productive focus, embracing multiple stories and identities and then being able to use storytelling as a way to draw yourself closer to others – rather than polarise them.

Listening to her in person was a beautiful experience. It served as a reminder of the optimism of will and hope – how not to feel disconnected or indifferent or atomised from the craziness of the world but to allow ourselves time and space to reflect, to empathise and understand the pain and suffering of others. In this day and age, a commitment to do that seems not a choice but a personal imperative.