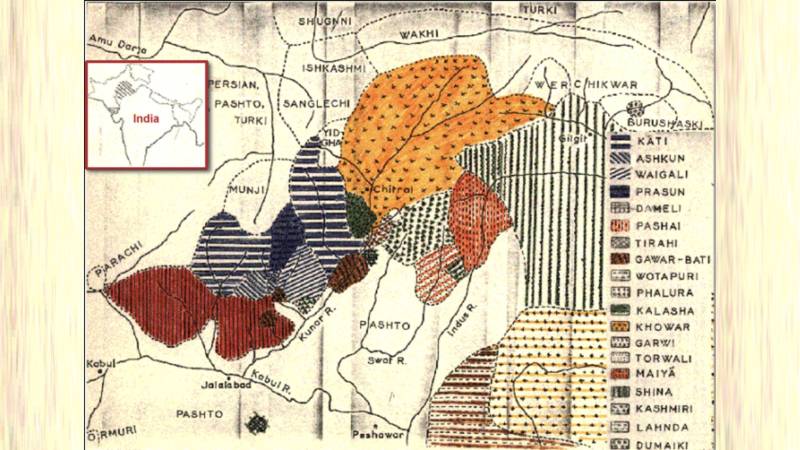

In the past, Dardistan was known for its unique Dardic customs, culture, and geographic boundaries. This region, diverse in linguistic and ethnic makeup, also served as a significant corridor for migrations between Central and South Asia. Influences from three major cultural zones—Persian, Indian, and Central Asian—along with Tibetan imprints, are evident in this region. This diversity, akin to the Caucasus, contributes to the area's remarkable linguistic variation. The Hindu Kush mountain range, referred to by the Greeks as Indicus Caucasus, is frequently mentioned in Dardic folklore as representing the mythical Caucasus.

The term Dardistan may seem burdensome to certain non-Dardic tribes and communities of this region. However, when we examine the pre-Islamic cultures of the area, they reveal a notable degree of similarity, albeit with some variations. These influences remain evident and would emerge prominently in a detailed study of the region. The term Dardistan is generally attributed to the renowned orientalist Dr Leitner, who referred to it as "Dardistan." However, the word Dārdistan (with an added "alif" after "daal") was used much earlier, in the 14th century, by Sang Muhammad Badakhshi in his book, Tarikh-e-Badakhshan to describe the region southeast of Badakhshan.

In Urdu, the English word "colonisation" is usually translated as Nauabadiyat, but this translation fails to fully capture its meaning. Nauabadiyat primarily pertains to the material aspects of colonisation, whereas the term encompasses non-material and often invisible processes that are its byproducts. These include subtler forms of colonisation that have emerged in modern times.

Internal colonisation, with its imposed notions of 'honour,' tribal and clan rivalries, and religious sectarianism, has deeply fragmented these communities

Another important aspect of colonisation is its timeline. It is generally linked to the British Raj, which was a particularly overt, organised, and brutal form of colonisation. However, the British colonisation is often criticised for three main reasons: its perpetrators were of a different religion and race, and it was a relatively recent phenomenon that remains vivid in collective memory. Secondly, internal collaborators played a significant role in perpetuating it; and thirdly, the Soviet Union, as a major adversary of British colonialism, had an influence on many who ideologically view the British colonisation through this lens, too.

In the Dardistani region—stretching from Laghman to Ladakh—colonisation began much earlier. Figures such as Alexander the Great and Emperor Ashoka implemented forms of colonisation. This intensified during the 8th to 10th centuries and reached a peak in the early 16th century. British colonisation, which followed, was more systematic, modern, and supported by institutions rooted in the Enlightenment. It also produced extensive documentation, leaving us with numerous accounts, writings, and tribal and military sketches from that period.

These waves of colonisation profoundly affected Dardistan. Massacres of local populations occurred, tribes and communities were displaced, and forced migrations within the region became commonplace. Consequently, linguistically and ethnically similar groups were separated and settled in different valleys, leading to significant changes in their languages and cultures. Encircled by harsh geographical barriers, many communities became isolated and unfamiliar with each other, gradually assimilating into the cultures of colonisers. Over time, the languages and memories of earlier generations vanished, replaced by the narratives, images, and cultures of the colonisers.

Some valleys, due to their inaccessibility, offered refuge to certain communities. However, regions south of this were particularly vulnerable, suffering severe consequences. The remnants of local languages in these areas largely survived due to limited mobility and the harsh geography.

Today, this region lives in obscurity and remains deeply affected by internal colonisation. For instance, the Pashai-speaking population north of Kabul and Laghman has either disappeared or been greatly diminished. In Nuristan, formerly known as "Kafiristan," colonisation was justified by labelling the local population as non-believers. After renaming it "Nuristan" and framing it under a single, homogenous identity, its internal diversity was overshadowed. Before this transformation, 64% of the so-called "Kafirs" were exterminated.

To the west of Nuristan lie Chitral, Dir, Swat, and Kohistan, whose identities are little known. For those with a religious lens, the 5,000 Kalasha community of Chitral is still perceived as "Kafiristan." This term has been used to rationalise discriminatory behaviour toward this minority. Across Malakand Division, Dardic communities lack significant political representation, cultural platforms, or a distinct voice. Many Dardic people and Gujjars align themselves with dominant ethnic groups, abandoning their native identities.

The vast cultural, administrative, and geographical divides within Dardistan have not only physically distanced these communities but also fostered prejudiced narratives about each other. For example, people from Gilgit, Hunza, and Chitral often view Swat as a hotbed of terrorism, while Kohistanis are considered backward. Conversely, the people of Swat, Dir, and Kohistan perceive Hunza, Gilgit, and Chitral communities as non-Muslims or, at best, not "good Muslims."

Internal colonisation, with its imposed notions of "honour," tribal and clan rivalries, and religious sectarianism, has deeply fragmented these communities.

Their indigenous social practices and institutions have largely disappeared. What remains are adaptations of colonisers' systems, which even the colonisers themselves may no longer practice.

Efforts to rescue these communities from internal colonisation require acknowledging the shared cultural elements among them, such as linguistic similarities and myths. Native intellectuals must play a crucial role, but they, too, are often complicit in perpetuating the dominance of external narratives. Pursuing state sponsored higher education often leads them to adopt the values and systems of the colonisers, abandoning their own culture and identity.

Is there a way forward? I am pessimistic but believe that efforts can still be made:

First, raising awareness about the region’s languages, cultures, and resources and conducting research to share these with others.

Second, politically mobilising for rights by breaking the elite monopoly over resources, though this should be seen as an ongoing struggle rather than a party-political effort.

Third, encouraging local intellectuals and activists to resist the dominant narratives and focus on ‘new localism’ in thought and practice.

While I have little hope that the current generation of local intellectuals can challenge dominant narratives, building their capacity for such a task remains vital.

One example of a positive effort is the book, Beyond the Mountains: Social and Political Imaginaries in Gilgit-Baltistan, edited by Dr Nosheen Ali and Aziz Ali Dad, featuring research by local writers and scholars. Published by Rachi Publications, its launch took place in Islamabad on 20 November 2014. Similarly, the Swat based organisation Idara Baraye Taleeem wa Taraqi (IBT) made a little effort through its Urdu publication Sarbuland with 40 papers by local writers from Dardistan.