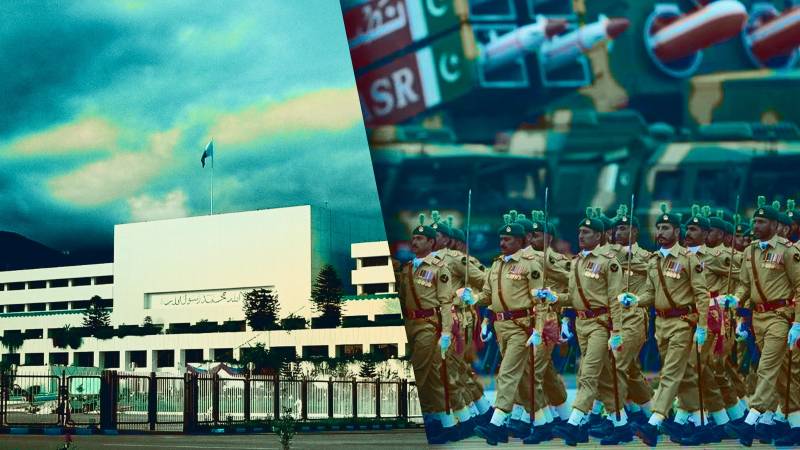

As we are subjected to the ignominious spectacle of the elections, the military’s attempt to control the outcome and the collusion of the various parties with the military in yet another desperate bid for power, we might think of what is tediously familiar and what might be new. PML-N and PPP willing to collude with the military to keep Imran Khan out merely repeats Khan’s own earlier collaborations. And yet, stunningly, the military has managed to hand over a significant segment of the population to Khan, regardless of who “wins,” even as it is unclear what exactly is being “won.” The country’s situation in what is being called a polycrisis is appalling: the rupee has been in freefall, the economy is a catastrophe, food insecurity (that euphemism for borderline starvation) is rampant, climate change promises ever more dire conditions.

As political parties vie for the status of first wife in a structure that looks like a dysfunctional marriage between codependent spouses, underpinned by occasional spousal abuse, the population at large and these issues remain outside the vision and discourse of the political establishment. The marital analogy is not frivolous. It is merited on the one hand by the absurd attempt to dissolve Khan’s marriage by invoking a violation of iddat—a move cynical, but more importantly, impressively stupid, which appears to have handed over women to PTI and its independent allies.

Whenever confronted with crisis, we return to some version of the question “can Pakistan survive?”, construed as a problem of territorial integrity, which then justifies yet another violent project of state centralization and a permanent stance of counterinsurgency towards the entire civilian population.

Tragically, one can imagine that someone somewhere thought they were being terribly clever. On the other hand, the marital analogy is elicited by the intimacy and symbiosis between civilian and military failure, which is hard to overstate, so, too, is the function each performs as alibi for the other. The oscillation between civilian and military power allows each side to blame the other for what is fundamentally a hybrid failure that goes back, pretty much, to the founding of the nation. One might think of the collusion between Sikander Mirza and Ayub Khan.

Whenever confronted with crisis, we return to some version of the question “can Pakistan survive?”, construed as a problem of territorial integrity, which then justifies yet another violent project of state centralization and a permanent stance of counterinsurgency towards the entire civilian population. This is not surprising; for when all legitimate political claims are perceived as insurgent and made so by the military stance toward democracy, counterinsurgency is a structural feature of the system and likely to be repeatedly operationalized by recourse to the imminent threat to the nation's territorial integrity.

At the same time, this is the moment to remember that the most dramatic compromise of the nation's territorial integrity was the rupture of 1971. That was the result of a civil-military alliance between Z.A. Bhutto and Yahya Khan, and of an unwillingness to accept election results which would have granted the then East wing the leadership. The question is not: can Pakistan survive as a territorial entity, but what form that survival will and ought to take as a political, civil and social entity? Indeed, as a viable political space.

Given our demographic transformations and the attendant transformation of the political sphere, which are happening regardless of the entrenchments in the political establishment, it is time to start shifting our focus from the contentless formalism of the civil versus military blame game. No one is clean in that game.

The military's current desperation is economic, but it is also prompted by the complete transformation of the population, 66% of which is under 35—young, social media savvy, rightly insistent upon their right to a future. These are not the Zia years, which continue to supply the political frame and a horizon of sorts for political thinking. Political silence is harder to generate. The neoliberalization of both the news media, as well as of social media has had the paradoxical effect of producing a population connected, and with access, to the rest of the world. Internet blackouts notwithstanding, this is unlikely to change.

As we lurch from (mostly self-induced) crisis to crisis, which, entirely paradoxically, has become a way to sustain stasis, can we pause for a moment and simply ask: what do we want this country to be in 50 years? In other words, what is the vision for the future? Do we have such a vision? More to the point, do we think we have a future? Given our demographic transformations and the attendant transformation of the political sphere, which are happening regardless of the entrenchments in the political establishment, it is time to start shifting our focus from the contentless formalism of the civil versus military blame game. No one is clean in that game.

Recourse to the United States may help stave off IMF and World Bank predation temporarily, but the US has its own crisis and nothing to offer by way of political ideas. What we need to do is reimagine the political space and the polity, and that reimagination has been stalled, interrupted, and outright assaulted since the inception of the nation by both military and civilian governments.

The crisis facing the nation right now cannot be addressed by a political class that is fundamentally out of touch with the changes within the population and in the global environment, not to mention the planetary one of climate change, which latter needs to be treated not merely as a conduit to gaining handouts that are not equitably distributed while environmental laws and urgencies continue to be ignored or actively violated. There is no rescue from outside. Short term political maneuvering masquerading as deep strategic thinking has been the military and civil national norm.

We need to change our political habits, revitalize our political imagination and discourse, and rethink our relation with the future. Given what is new, the demographic shift and the climate crisis, we can only maintain the status quo ante through profound state violence and an immiseration that has already crossed class lines.