“It is better to live your own destiny imperfectly, than to live an imitation of someone else’s life with perfection.” Bhagavad Gita 18.47

At first glance, this seemingly colloquial phrase seems to fit in perfectly with what your run of the mill self-proclaimed (mostly Western) influencer ‘gurus’ would style their social media feeds with under the repulsively trite guise of being spiritual guidance from the mystical realms of the east. But setting our own prejudicial Pakistaniyat aside for a second needs to be considered a mandatory necessity rather than a choice, as it is only through the objective lens of almost fervent candour that we can truly begin to comprehend the absolute marvel that is the Bhagavat Gita. Withstanding the relentless test of time, the scripture has served as a means of enlightenment, healing, teaching but perhaps most importantly; the role it has served as a source of inspiration for billions across millennia through the contextualization of its abstract to a more tangible reality.

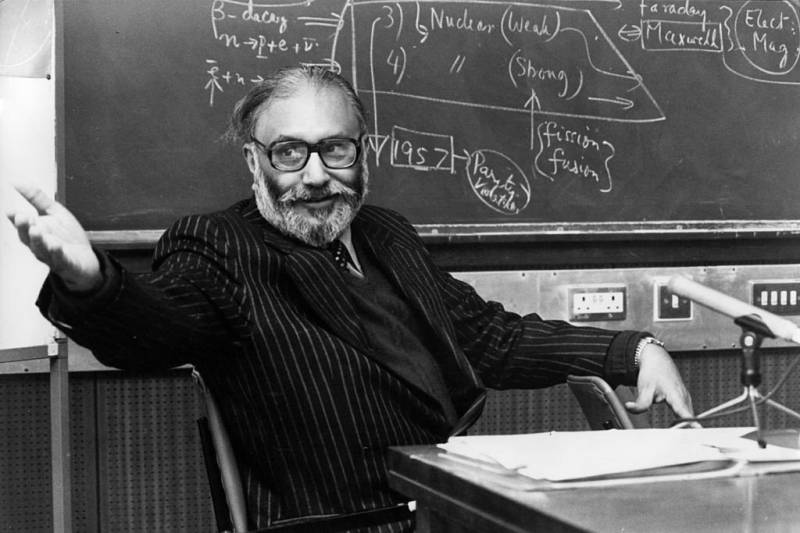

One such inspired soul was that of J. Robert Oppenheimer, whose rather astute quotation from the Gita has forever been etched into the annuls of history – always to be ushered in the same breath as the most destructive force ever to be harnessed by mankind, garnering gravitas that transcends its original source. But as Oppenheimer finds himself re-popularized around the world due to last summer’s blockbuster bearing his name, we turn to our own scientific promethean in Dr. Abdus Salam. Pictures and videos of Salam alongside the father of the atomic bomb had flooded social networks all over the country, only to serve as a bleak reminder of the eternal torture Prometheus was subjugated to for stealing fire from the Gods and giving it to mankind. Alas, the treatment of the undeniable figurehead of Pakistan’s scientific pantheon (measly as it may be) draws attention not to the quote uttered by Dr. Oppenheimer but rather to 18.47, and how it delineates the tale of a country which lost its identity – and by extension itself.

Be it the Quaid’s infamous Dhaka address mandating the use of Urdu as the national language or the abhorrent replacement of the term “states” with “state” in the Lahore Resolution of 1940 - a bitter lesson Pakistan has had to learn through a journey marred by a desire for unity at the expense of its own diverse identities is false constructs are nothing more than feeble houses of cards. A naive pursuit, reminiscing us of the ill-fated "One Unit" policy of 1955, that put into motion the reduction of the distinctive regional, cultural, and social identities of the nation into a monolithic, uniform mould. A futile effort, akin to suppressing the manifold voices of a choir in favour of a monotonous single tone.

As history has shown, a nation's strength lies in the harmonious unity of its diverse parts. Take, for example, the United States, a country thriving with diversity, where each state holds its unique attributes and autonomy, and it is this very construct that allows for the space for them to come together and form a robust union.

Yet, Pakistan, in its misguided attempt to imitate such models, ignored its own realities. These regions, with their distinct languages, cultures, and traditions, were forcefully homogenized, resulting in the loss of a rich tapestry of identities – a loss which resonates inexorably in our national conscience amplifying the sentiment of a Pakistan truly and agonizingly lost.

The halls of historical interpretation don’t offer much better, as we are confronted with an even more disconcerting picture. The late K.K. Aziz, in his seminal work "The Murder of History," paints a definitive picture of how historical facts in Pakistan have been distorted and moulded to fit the state's narrative. Textbooks, instead of promoting inquiry, critical thinking, and nuanced understanding of the past, became instruments of state propaganda. The 1971 Fall of Dhaka, a painful chapter in our history, has been minimized to a mere footnote, its painful truths omitted or twisted to suit the national narrative.

Such historical revisionism echoes loudly in the tale of Dr. Abdus Salam. Despite becoming the first and only Pakistani to win a Nobel Prize in the sciences and having served as the most instrumental figure in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, his achievements were overshadowed in the public discourse due to his faith. An entire generation grew up largely unaware of his monumental contribution to the field of theoretical physics and his role in promoting science in Pakistan. Our quintessential Pakistani Prometheus.

This saga, reminiscent of 18.47 yet again is a bleak mirror of our country's narrative. Instead of embracing our imperfections and differences, we have sought what can only be termed as a perfected illusion - a decision that has amounted to nothing more than a continuing, ever-present mass identity crisis.

However, history, as we know, is not just a chronicle of failures but also a testament to the resilience of nations. Pakistan stands at a crossroads, its future waiting to be written. The 18th Amendment provided us with a glimmer of hope of a much-needed devolution of power, yet the question remains - will we continue down the path of distorted history and forced homogeneity, or will we embrace our diverse heritage, and strive for a more authentic and inclusive national identity? An identity hinged not on uniformity, but collective progress through our own unique differences serving as our strength.

The answer lies in our actions. Yet again the Gita serves its infallible purpose by advising: "You have the right to work, but never to the fruit of work." The journey to rediscover our past may be fraught with discomfort and revelations, but it is only through this process that we can reconnect with our diverse identities, learn from our mistakes, and strive for a more truthful, inclusive future.