October this year is special for those in the Indian Subcontinent who profess to be on the Left and have dedicated their lives for the emancipation of the poor and oppressed against the curses of imperialism, capitalism, feudalism and religious fundamentalism. October 17 next week will mark the end of the centenary celebrations of the historic Communist Party of India (CPI) in Tashkent; while October 10 today marks the finale of the otherwise-muted birth centenary commemorations of Abdullah Malik, one of the pioneering stalwarts of the CPI from Punjab.

Malik was born in Kucha Chabuksavaraan, a historic mohalla of old Lahore. He was educated at Lahore’s Government College and Islamia College and became active on literary, journalistic and political fronts from his college days. On one hand, he remained the editor of the Islamia College magazine The Crescent and on the other, he also remained active in the Majlis-e-Ahrar youth for a while and then the president of its annual conference. Then he joined the CPI as a fulltime member in 1942 and remained at the forefront of its magazines in Lahore and Bombay. He also continued working with Sajjad Zaheer, Syed Sibte Hasan and Sardar Jafri in Qaumi Jang, the party paper from Bombay. After the creation of Pakistan, he remained attached with the Pakistan Times and Imroz for 30 years. He had to endure the hardships of jail and the Lahore Fort multiple times in united India and Pakistan because of his progressive and left-wing views. He wrote almost 35 books based on educational, literary, political and travel topics. Among them the quartet of books on the army and higher power are a unique example of its genre, which till now has not been researched upon. For 12 years continuously, Malik wrote a column with the title of Hadees-e-Dil (Hadith of the Heart), first for daily Pakistan and then for the daily Nava-e-Vaqt until the last days of his life. One finds the fountains of movement and history issuing out of his columns. He held a deep observation of the activities of the opposition and ruling parties in Pakistan in the last six decades. Not only this, he also deeply studied the changes occurring in the world political landscape. Eventually the Progressive intellectual and researcher who had spread the rays of consciousness in the pages of history offered himself up to the following couplet of his comrade Faiz Ahmad Faiz on April 10 2003:

Pal bhar ke liye yoon hi aankh lagi thi

So kar hi na uthen ge yeh iraada toa nahi tha

(The eyes had closed merely for a moment of hibernation

That we would never wake up was not our inclination)

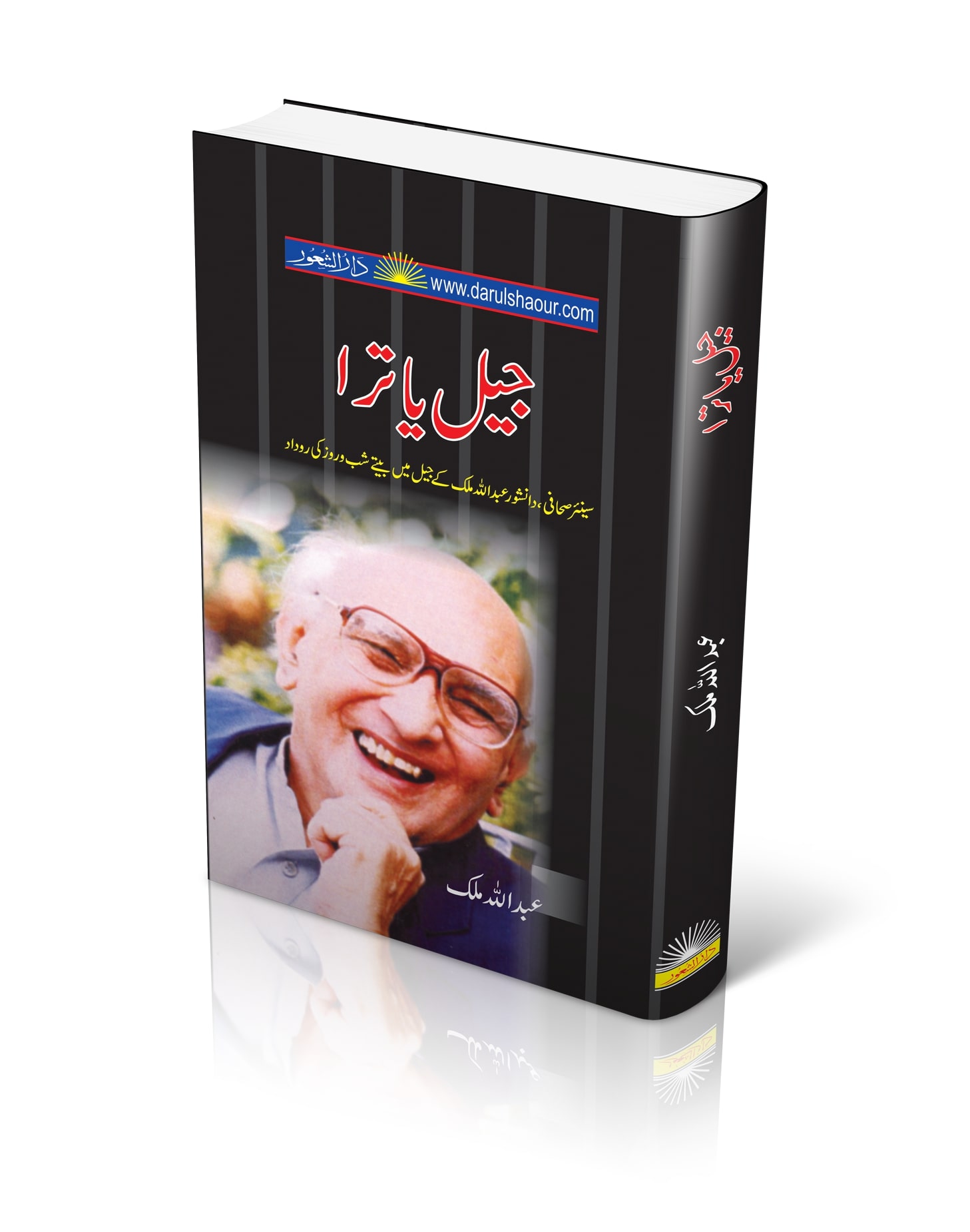

Malik was a meticulous diarist, which yielded a rich harvest of authentic and interesting books: the first book of this series was his eminently readable autobiography Purani Mahfilen Yaad Aarahi Hain (The Old Gatherings Are Coming To Mind), consisting of the first 27 years of his life until partition, published in his lifetime; Jail Yatra, the tale of his jailtimes; and an intriguing travelogue of his pilgrimage to Makkah, named after his columns as Hadees-e-Dil.

Abdullah Malik’s punishment: a year in prison, fine and in view of his old age, flogging was spared. Malik’s stance was ‘I am ready to be flogged but do not spoil my market by calling me aged.’

Jail Yatra is the tale of the tumultuous period of various martial laws in Pakistan, when all basic rights had been seized and justice was being blown to smithereens. Malik’s habit of writing a diary regularly has provided such a treasure trove of information to the historians of Pakistan which they would always keep referring to. The observations of captivity and imprisonment upon which the book is based too contain invaluable material for historians and observers of political and social conditions; it is a little-known but important contribution to the long tradition of prison literature written by the likes of Maulana Zafar Ali Khan, Maulana Hasrat Mohani, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Bhagat Singh, Shorish Kashmiri, Ibrahim Jalees, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Zafar Ullah Poshni and Hameed Akhtar. Some of Malik’s comrades from his days in prison like the venerable nonagenarians and long-time residents of Lahore I.A. Rehman and Rauf Malik (Malik’s younger brother) until their very recent deaths this year and a few younger ones like Amin Mughal, Ehsan Wyne and Aitzaz Ahsan were/are still around to confirm and corroborate these accounts. During the days of East Bengal being referred to as Bangladesh, Malik alongwith the aforementioned Akhtar and Rehman were responsible for editorial affairs at the daily Azad and therefore were in a position to have a ringside view of the whole episode. When the freethinking innocents were jailed for their innocence in 1981, Rahman spent the first three months with Malik (but these three months are not mentioned in this book). The purpose of mentioning this detail is merely to clarify that the verification of Malik’s narrative is not based on hearsay but the direct observations of his living comrades like Rahman.

The case made against Malik for referring to the struggle of the people of East Bengal as the struggle of the people of Bangladesh is of historical importance. Our misfortune was not just that that the Pakistani state was treating its compatriots as enemies and was oppressing Bengali Pakistanis in myriad ways. This matter too was a source of shame and sorrow that in West Pakistan, especially Lahore, the people were content and happy that the murderers of the people in East Bengal were the trustees of the tradition of Siraj-ud-Daulah. There was a tiny group in Lahore, among whose leaders the name of Malik was very high, which kept holding the flag of truth and justice with great honesty and tried to respect the collective interests of the Pakistani people. Abdullah Malik had this distinction that he was not only a towering journalist, but his acquaintance with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Sheikh Mujib sometimes touched the limits of friendship. Malik tried for a long time that a consensus emerge between these two politicians regarding the political future of the country; something which had become impossible, Malik’s attempt could not make it possible. These things are not mentioned in Jail Yatra, maybe Malik has shone light over it at some other place in his diary. However at a delicate turn of history, the attempt of Malik should definitely be recorded somewhere.

Very few people know that Malik was also a poet along with being a successful author. He composed little poetry and spent the life of a successful journalist having a deep vision over current affairs

After reading the detail of the case against Abdullah Malik, readers can well realise what state the dictatorship of Yahya Khan had reduced the judicial system to; whatever the dictatorship of Yahya Khan did, the same was done by other military dictators of Pakistan. Three scenes from this case are worth preserving for posterity.

When news of Malik’s arrest spread, his comrades contacted Colonel Aqeel of the ISPR, who never refrained from decency even in uniform and was known to a few of the former; they alongwith Colonel Aqeel visited the jail of Mughalpuara thana. What they saw was that Malik was (apparently) asleep on the velvety floor of dirt, as if resting in some five-star hotel, not in jail. This was an important aspect of Malik’s personality in that he had the ability par excellence to bear the consequences of his words and actions with liveliness.

The second picture is that of the military court before which the case against Abdullah Malik was presented and which to call a court is akin to insulting the court. Many of the accomplished lawyers of the city were present for the defence of the accused but according to the law of the military court, they could neither say anything to the court neither rebut the evidence of the police witnesses; both these tasks were also performed by Abdullah Malik himself. The manner was the same, Abdullah Malikite, as if about to attack the adversary now, and questions or protest in a thundering tone and with the customary assault of words. Meaning ‘I know that I am about to be punished, but am adamant.’

The third scene is that of the day of judgement. Malik had a good habit that he deemed it necessary to be bound by respect for the appointed time for every engagement. So well before the start of the session of the military court he alongwith I. A. Rehman reached Peoples House and both began to wait for the authorized officers on the steps outside the court. It was the day of the judgement and he was aware of the equitability of the military court as well, but no movement of Malik betrayed any concern, there must be a weight upon the heart but it was necessary to preserve the dignity of the political worker. Well, the session of the military court began, for some time there was a meaningless exchange of words and it was declared that the verdict will be announced after the tea break. It was witnessed that during the 15-minute break, the presidents of the military court were having tea in the attached room. Then the higher officer began to read a typed judgement after arriving in the courtroom and this activity took more than 15 minutes (during which the verdict was written and typed), because it was necessary to narrate the story of the creation of Pakistan in the judgement. Abdullah Malik’s punishment: a year in prison, fine and in view of his old age, flogging was spared. Malik’s stance was ‘I am ready to be flogged but do not spoil my market by calling me aged.’

This was the state of the nation in 1971, people who had been making the absurd claim of improving the race of Bengali Pakistanis, or wanted to capture relinquished properties in Dhaka, or at least were entertaining the people of West Pakistan with lies, they were deemed worthy of reward, and the crazy people who tried to bare the facts were deemed punishable by imprisonment and economic exploitation.

The other strange tale in Jail Yatra is about the arrest of those individuals who General Zia-ul-Haq had made the target of his strategy of giving permanence to his illegal government. He was concerned about the creation of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy, the kidnapping of the PIA plane gave him an opportunity, to issue a P.O.C. through which he got the excuse to reduce the authority of the higher courts and imprison the democratic-minded individuals together with the workers of the Peoples Party.

Malik had suffered imprisonment before, first as punishment for the crime of attempting to create Pakistan and later for struggling for a system based on democratic and social justice in the country; but this captivity was different, he was given a good Class, there was a good number of friends among fellow-prisoners, folks from home used to come visit and better-than-required food was available. There were opportunities too for reading and writing; but prison is after all prison. There was less hardship compared to captivity in the chambers of the Lahore Fort; but there the movement in society gave support, here the absence of an effective movement was a cause of restlessness. One grief that freedom was seized without doing anything, another that freedom was made conditional upon filling an insulting bond, and the biggest grief that there were no signs of going further than the starting point of the movement against the Zia dictatorship. Malik has recorded this tale keeping in mind the personal tradition of righteousness, love for detail and seasoning prose with verse. In this part, circumstances change little and Malik has greater opportunities for knowing and comprehending. It has a ‘thing of pleasure’ too and methods of dealing with the demands of time as well.

Awareness of the events of the destruction of the garden in 1971 and 1981 and meeting Abdullah Malik in these pages, is a profitable trade, not a loss-making one for the present generation, ‘especially for young Pakistanis.’

Very few people know that Malik was also a poet along with being a successful author. He composed little poetry and spent the life of a successful journalist having a deep vision over current affairs. In this book, he has included the verses of the renowned poets of the country as well as Ghalib. This makes his writing appear more beautiful; usage of verses according to the occasion, this was his expertise alone.

Then in his Hajj travelogue Hadees-e-Dil subitled Aik Kammunist ka Roznaamcha-e-Hajj (A Communist’s Hajj Diary) published in 1973 and recorded within the two holiest Islamic cities of Mecca and Medina, as well as the latter’s Masjid-e-Nabvi (The Prophet’s Mosque) is a totally unique experiment in Urdu literature, perhaps even the Muslim world. In it Malik makes a provocative claim about the Hajj pilgrimage, and by extension, Saudi Arabia. He argued that the ritual as it exists is an Islamic dystopia: a (Saudi) society not to be emulated by Pakistan, but that could change if a Progressive government is established in Riyadh; and the Hajj pilgrimage could be used for far-reaching results, and a means to free Muslims everywhere from their subservience to the West. For example, an extract from Malik’s entry on December 29, just two days into beginning the diary, reads as follows:

‘At this time I am sitting atop the upper roof of the Haram. The cold air is refreshing and that Turk has expressed his friendship and love by rubbing me with perfume. This internationalism is so heart-charming. This was a totally new experiment. One had experienced it in communist congresses and conferences. There is a scientific manner of thinking in that internationalism but this internationalist intimacy has a spontaneity; if this intimacy is armed with scientific manner of thinking, then it too can become a very great power and in this respect when a progressive government is established in Saudi Arabia tomorrow, then it would make this great congregation so useful and beneficial for mankind and if suppose tomorrow a government of socialist views is established in Saudi Arabia, then conservative Muslim governments would prohibit going for the Hajj! This too happens.’

Malik remained steadfast in his communist beliefs even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, unlike many of his comrades who either abandoned the cause altogether (one thinks of Sardar Jafri who was famously compelled to write a poem denouncing the need for a red flag) or sought refuge in business, Non-Governmental Organizations and religion. In his last days he was not content with the political landscape of Pakistan. He was a progressive thinker and wanted to see traces of happiness upon the faces of the residents of this country. All his life, he spoke for the rights of the workers; raised the thought of the poor and wretched; and always sided with truth.

Since Marxists do not believe in graves or urs like saints, I want to mention in closing that Malik’s younger brother Rauf Malik, who turned 95 earlier this month on October 1 and passed away on May 29 earlier this year, had informed me that the former had in fact dissociated himself from the latter since 1969 owing to a property dispute between the two brothers. Rauf sahib has mentioned this in mind-numbing detail in a pamphlet titled Qissa-e-Jankaah (The Afflicting Tale), published in 1974 and for limited circulation among the Maliks’ relatives and close family. It is dedicated to Abdullah Malik’s two sons Kausar and Sarmad, ‘who have been deprived of the permanent love of their real paternal uncle due to their father’s unbridled lust for gold.’ Rauf sahib told me that despite the intercession of comrades and close relatives over a period of time, the dissociation lasted till his elder brother’s passing away in hospital, where the younger brother kept hoping that the elder brother would say a word or two in his dying moments to the younger regarding this treatment. At the end of Abdullah Malik’s centenary year today, is it too much to ask for his sons to recognize and redress their late uncle’s legitimate grievances?

All translations from the Urdu are by the author.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He is translating Abdullah Malik’s book ‘Hadees-e-Dil’ (Hadith of the Heart) into English. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com