After a month of living in Islamabad, I was perusing the impressive collection of works at Ejaz Books. In the English literature section, I was shocked to find not one but two copies of a book written by my great-great-great-great uncle by marriage, RM Ballantyne, entitled The Coral Island. Having only read some excerpts as a child, the initial surprise was quickly replaced by a sense of disgust at the imperialist and racist narratives at the heart of the book; narratives inherent to the British colonial project particularly because of the research I am currently conducting here is on the topic of decolonisation.

Decolonisation can mean several different things. In a formal sense, it means the process by which a people gain political and economic independence from a colonising power. Pakistan and India’s independence from the British in August 1947 is one such example. It can also mean the process by which a country removes colonial legacies that survived independence from educational, legal, military, and economic systems, or in the forms of infrastructure or street names. But, within the realm of ideas and knowledge production, decolonisation means the identification and dismantling of colonial ideas that glorify and prioritise Western or Eurocentric society, culture, language, and scholarship as inherently superior to their non-Western, non-Eurocentric counterparts. This is followed by the consequent reclaiming and centering of indigenous modes of knowledge, wisdom, communication, and culture. With the example of Ballantyne’s book above, this can extend to literary theory, too.

Indigenous scholars from around the world have long been, and continue to be engaged in processes and studies of decolonisation. They rightly show how formal decolonisation was not a one-sided act by colonial and imperial administrators but affected by the people's defiance and resistance. They speak authoritatively on what constitutes indigenous ideas, wisdom, and culture that should replace their colonial equivalents and be acknowledged in their own right. In this sense, decolonisation is best enacted and led by Indigenous scholars, practitioners, and ordinary people themselves.

But those of us from countries with colonial histories must be prepared not only to acknowledge the past but to engage in processes of decolonisation led by Indigenous scholars and initiate conversations on the subject. If we truly seek to tackle persisting inequalities that are rooted in colonial Eurocentricism, then we must commit to decolonisation by addressing the concerns of Indigenous communities.

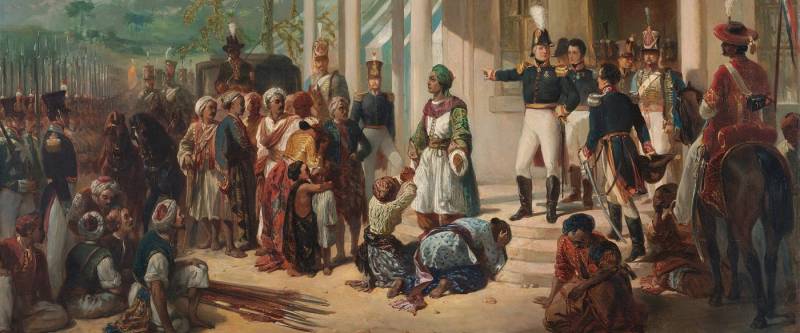

We were taught less about the impact of colonialism on the people who were oppressed under colonialism. Less about how the British claimed to be a force for good, self-avowedly bringing ‘civilisation,’ Christianity, ‘equality and justice’ to the colonies, while its trading and colonial manifestations looted and redirected resources, reduced people to second-class citizens in their lands and was complicit by act and omission in the deaths of hundreds of millions of people.

One of the most important lessons that university taught me is how unprepared even the younger generations of the UK are for discussions about colonialism and decolonisation. I certainly was. We were often taught at school about the impact of the Empire on Britain domestically, such as in terms of economics and immigration, or on international relations between Britain and the other so-called ‘great’ powers, which have shaped British approaches to foreign policy today.

But we were taught less about the impact of colonialism on the people who were oppressed under colonialism. Less about how the British claimed to be a force for good, self-avowedly bringing ‘civilisation,’ Christianity, ‘equality and justice’ to the colonies, while its trading and colonial manifestations looted and redirected resources, reduced people to second-class citizens in their lands and was complicit by act and omission in the deaths of hundreds of millions of people. Less about non-Western philosophical and religious traditions that have impacted the world as we know it, beyond the European and Greco-Roman lenses.

Then, when we combine this with the emphasis on the abolition of slavery as a testament to the true character of Britain, the so-called ‘positives’ of empire, and the frequent allusions today to ‘British values’ (democracy, rule of law, individual liberty, mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs) and tackling its antithesis around the world, we are led to believe that Britain has, overall, been a force for good throughout history. Leaders like Winston Churchill continue to be venerated, while his policies directly contributed to the Bengal famine of 1943, in which three million people died, and his racism was swept under the rug. Unless we have taken the initiative ourselves, we are woefully unprepared to have conversations with members of the same generations from formerly colonised nations who have been educated about the realities of the British Empire’s colonial project, thereby knowing more about our country’s history than we do.

Discussions about decolonisation and reparations, particularly for slavery and climate change, are becoming increasingly commonplace, not only in academia but within international relations. The CARICOM Reparations Commission is the leading body with regard to the former, seeking to establish the case for reparations from former colonial powers to the people of the Caribbean community for their part in slavery, genocide, and crimes against humanity.

We have also seen an increased discussion around the funding that countries like the UK and the US should give for their contribution to climate change. Referred to as the “loss and damage” fund, it is designed so that so-called ‘developed’ countries pledge funds to ‘developing’ countries to help alleviate the cost of unavoidable loss and damages incurred as a result of climate change, which they suffer from disproportionately in terms of their historic contributions to global emissions (note the neo-colonial dichotomy of developed/developing). It was the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) that first spearheaded advocacy on this issue, with Pakistan playing an important role in presenting and reaching the deal at COP27. Leaders of countries vulnerable to climate change thus often refer to such funds as ‘reparations,’ though neither the US nor the UK accept these terms. The Scottish government under Nicola Sturgeon in 2021 was the first government to provide such funding and she even referred to it as “an act of reparation.”

The Labour government has only just announced this month that the UK will hand sovereignty of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, having forcibly removed the Indigenous Chagossians in the 1960s to create a military base during a period largely characterised as one of decolonisation.

This is not to say that no recent progress toward decolonisation has been made. Corinne Fowler, Professor of Colonialism and Heritage in Museum Studies co-authored a report into direct and indirect links between properties in the care of the National Trust and colonialism and slavery, including those built or sustained by members of the East India Company and the British Raj. Professor Fowler has also written a book on how colonialism impacted quintessential rural life in Britain. A family descended from slave owners has apologised and paid personal reparations for their ancestral history, and it has also been reported that members of the unelected House of Lords whose ancestors benefited from the slave trade may lose their seats.

Furthermore, the Labour government has only just announced this month that the UK will hand sovereignty of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, having forcibly removed the Indigenous Chagossians in the 1960s to create a military base during a period largely characterised as one of decolonisation. While described as a “significant milestone in its decolonisation process,” because it marks the return of the UK’s final colonial territory in Africa, the exclusion of Chagossians from the negotiations and the retention of one island serving as a US military base undermine the commitment to full decolonisation.

Additionally, British educational, cultural, and governmental institutions must prepare the younger generations not only to learn from the past, so that such injustices are not committed again but more generally to be able to operate in an increasingly international and intercultural professional landscape. The suggestion that the British can learn more about its history by looking abroad is completely true in light of colonialism and, at the very least, those working within government, the civil service, and the foreign office should be required to study this history to inform their work.

Colonialism has shaped both the UK’s international relations and the perceptions of other countries towards the UK. The way we have been taught to perceive ourselves is not representative of how many in the Global South perceive us. Having leaders who are both unwilling and ill-prepared to have difficult conversations about colonialism and its ongoing legacies should be a source of concern for us as a country.