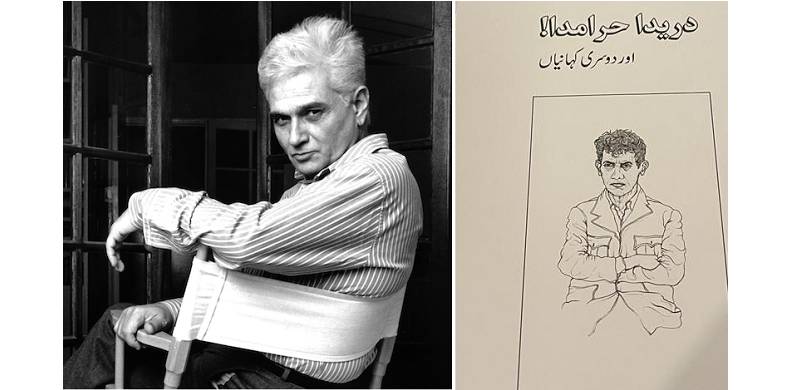

The title story of Julien’s short story collection Derrida Haramda! introduces us to Shahid Wirk (or, as he is lovingly called by his friends, Sheeda) from Sheikhupura, who writes a surreal novel “Nazia” inspired by André Breton’s iconic surrealist work Nadja. Shahid’s novel is as an absurd piece of writing about a strange woman who haunts the streets of Sheikhupura. The narrator follows the woman at night, walking the city’s empty streets, and as he walks and walks, he is slowly confronted by the alienation he feels in the city, whose streets have emptied as if the city had been wiped clean of humans and animals by a poisonous gas. Julien’s stories often engage these peculiar and, at times, monstrous relationships and affiliations between European and South Asian creative work.

For example, one story follows Stephen, a British filmmaker who is trying to recreate Macbeth in the Cholistan Desert, and another story, “Feroz Iqbal ki Chori,” introduces us to a Pakistani musician who composes Western classical music inspired by folktales such as Heer Ranjha for the prestigious Royal Albert Hall in London. In these and other stories, Julien’s mixture of supposedly distinct Western and Eastern forms often hints at the worldly realities that shape literature and its audiences. Instead of simply writing about aesthetic considerations, the genius of writers, the importance of influence, and other such questions of traditional literary criticism, Julien exposes the geopolitical conditions, economic realities, and intimate human relations that shape the writing of literature and its worldly circulation.

The title story is an interesting representation of the way European theory and its famous concepts, such as deconstruction, cannot simply be understood as abstract, universal, and politically neutral reading strategies that are as applicable in Pakistan as they are in France. Julien shows how these concepts are historically produced ideas that change as they travel through the world.

The protagonist, Sheeda, after being impressed by surrealism finds a new obsession: Jacques Derrida. The son of a feudal family, he moves from Sheikhupura to Lahore to start college, where he is introduced to the writings of the French literary theorist. However, Sheeda soon gets into trouble with other students due to his unorthodox religious beliefs and, funded by his father’s money, flees to Paris, where he takes Derrida’s seminars. He studies French, reads everything Derrida has written, and attends his seminars with an unmatched sincerity and seriousness of purpose. He eventually returns to Pakistan on his father’s insistence.

Then Sheeda hears the news that Derrida is coming to visit Lahore, where he will give a lecture at Forman Christian College. Sheeda, as expected, is elated. He travels to Lahore and sits in the seminar, unable to believe his own luck. At the end of the seminar, he finally gathers the courage to put a question to his idol. He asks Derrida about the uses of deconstruction for someone like him, someone who loves the subversive potential of deconstruction, but who has grown up in a religious and feudal environment. To his great disappointment, Derrida does not answer his question, only smirks. Sheeda is deeply affronted by the silence and the smirk. He decides to follow Derrida around the city in order to get an adequate answer from him, and so begins a rather absurd journey. He follows Derrida to his hotel, then to an art gallery, and from there to a Jewish graveyard in the middle of a forest on the outskirts of Lahore, and finally, back to his hotel, where he watches Derrida give an interview to a local journalist. Throughout the trip, Sheeda’s frustrations accumulate. He is unable to access Derrida because wherever the Frenchman goes, he is insulated by barriers of class and culture that do not permit Sheeda to enter. Finally, Sheeda loses his patience, walks up to Derrida in the hotel lobby, and slaps him across the face. After this incident, Sheeda disappears, never to be seen again.

It is, of course, a famous criticism of deconstruction that it doesn’t pay enough attention to the socio-political realities of human relations in the real world, preferring to ponder over the textual relations of linguistic signs on the page. Julien overturns this script – forcing theory to confront the world. Instead of focusing on the textual nuances of deconstructive theory, Julien prefers to show us how this theory actually reaches Sheeda, a small-town man of modest privilege from Pakistan, how he becomes obsessed with it, how his obsession is ridiculed by his friends, and how he fails to make a connection with Derrida himself. The other stories also follow this pattern. Julien consistently undermines the foreboding sanctity of so-called Great Literature and Great Writers to focus, instead, on the human weaknesses and political compulsions that surround the work of literature. For example, the second story in the collection, “Mutarjima,” narrates the relationship between a semi-fictional version of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and his Russian translator, Ludmila Vasilyeva. Most writers, when fictionalizing someone as famous and influential as Faiz, would proceed with caution. But Julien delights and revels in the murkier aspects of writers’ lives. He depicts him drinking and partying, inappropriately flirting, surrounded by sycophants, and writing glowing works about the Soviet Union while turning a blind eye towards the faults of the communist regime.

My favorite story in the collection, “Manhoos Angrez,” is about Stephen, a filmmaker and a drug addict, who arrives in Lahore from England to teach filmmaking. While he is a brilliant teacher, Stephen is also a pathetic white man who never misses a chance to complain and condescend to his generous hosts. After being challenged by one of his students, Stephen decides to make a film in Pakistan, only to show everyone that he can make a great work of art even in a backward and underdeveloped country like Pakistan. But he runs into various hurdles: the unbearable heat, people in the film industry not taking him seriously, producers requiring him to compromise on his creative vision, faulty equipment etc. The resulting film flops in cinemas and Stephen decides to run back to England, but gets caught at the airport with drugs. The narrator of the story, a Pakistani student who seems to be in love with Stephen, finally gets tired of Stephen’s condescension and lies, leaving him to rot in a Pakistani jail.

Julien’s fictional khakas are far from the usual glowing portraits that testify to the rarefied status of literature. They are about flawed people, like the rest of us, burdened by human weaknesses and compromising with their social and economic circumstances. In them, Julien shows, with his characteristic mix of satire and tragedy, that literature is not revealed from the skies or conceived immaculately on the page. It exists in the world. It gets its hands dirty. But its earthly reality is precisely what makes it interesting, what keeps us turning the pages.

For example, one story follows Stephen, a British filmmaker who is trying to recreate Macbeth in the Cholistan Desert, and another story, “Feroz Iqbal ki Chori,” introduces us to a Pakistani musician who composes Western classical music inspired by folktales such as Heer Ranjha for the prestigious Royal Albert Hall in London. In these and other stories, Julien’s mixture of supposedly distinct Western and Eastern forms often hints at the worldly realities that shape literature and its audiences. Instead of simply writing about aesthetic considerations, the genius of writers, the importance of influence, and other such questions of traditional literary criticism, Julien exposes the geopolitical conditions, economic realities, and intimate human relations that shape the writing of literature and its worldly circulation.

The title story is an interesting representation of the way European theory and its famous concepts, such as deconstruction, cannot simply be understood as abstract, universal, and politically neutral reading strategies that are as applicable in Pakistan as they are in France. Julien shows how these concepts are historically produced ideas that change as they travel through the world.

Sheeda hears the news that Derrida is coming to visit Lahore, where he will give a lecture at Forman Christian College. Sheeda, as expected, is elated

The protagonist, Sheeda, after being impressed by surrealism finds a new obsession: Jacques Derrida. The son of a feudal family, he moves from Sheikhupura to Lahore to start college, where he is introduced to the writings of the French literary theorist. However, Sheeda soon gets into trouble with other students due to his unorthodox religious beliefs and, funded by his father’s money, flees to Paris, where he takes Derrida’s seminars. He studies French, reads everything Derrida has written, and attends his seminars with an unmatched sincerity and seriousness of purpose. He eventually returns to Pakistan on his father’s insistence.

Then Sheeda hears the news that Derrida is coming to visit Lahore, where he will give a lecture at Forman Christian College. Sheeda, as expected, is elated. He travels to Lahore and sits in the seminar, unable to believe his own luck. At the end of the seminar, he finally gathers the courage to put a question to his idol. He asks Derrida about the uses of deconstruction for someone like him, someone who loves the subversive potential of deconstruction, but who has grown up in a religious and feudal environment. To his great disappointment, Derrida does not answer his question, only smirks. Sheeda is deeply affronted by the silence and the smirk. He decides to follow Derrida around the city in order to get an adequate answer from him, and so begins a rather absurd journey. He follows Derrida to his hotel, then to an art gallery, and from there to a Jewish graveyard in the middle of a forest on the outskirts of Lahore, and finally, back to his hotel, where he watches Derrida give an interview to a local journalist. Throughout the trip, Sheeda’s frustrations accumulate. He is unable to access Derrida because wherever the Frenchman goes, he is insulated by barriers of class and culture that do not permit Sheeda to enter. Finally, Sheeda loses his patience, walks up to Derrida in the hotel lobby, and slaps him across the face. After this incident, Sheeda disappears, never to be seen again.

It is, of course, a famous criticism of deconstruction that it doesn’t pay enough attention to the socio-political realities of human relations in the real world, preferring to ponder over the textual relations of linguistic signs on the page. Julien overturns this script – forcing theory to confront the world. Instead of focusing on the textual nuances of deconstructive theory, Julien prefers to show us how this theory actually reaches Sheeda, a small-town man of modest privilege from Pakistan, how he becomes obsessed with it, how his obsession is ridiculed by his friends, and how he fails to make a connection with Derrida himself. The other stories also follow this pattern. Julien consistently undermines the foreboding sanctity of so-called Great Literature and Great Writers to focus, instead, on the human weaknesses and political compulsions that surround the work of literature. For example, the second story in the collection, “Mutarjima,” narrates the relationship between a semi-fictional version of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and his Russian translator, Ludmila Vasilyeva. Most writers, when fictionalizing someone as famous and influential as Faiz, would proceed with caution. But Julien delights and revels in the murkier aspects of writers’ lives. He depicts him drinking and partying, inappropriately flirting, surrounded by sycophants, and writing glowing works about the Soviet Union while turning a blind eye towards the faults of the communist regime.

My favorite story in the collection, “Manhoos Angrez,” is about Stephen, a filmmaker and a drug addict, who arrives in Lahore from England to teach filmmaking. While he is a brilliant teacher, Stephen is also a pathetic white man who never misses a chance to complain and condescend to his generous hosts. After being challenged by one of his students, Stephen decides to make a film in Pakistan, only to show everyone that he can make a great work of art even in a backward and underdeveloped country like Pakistan. But he runs into various hurdles: the unbearable heat, people in the film industry not taking him seriously, producers requiring him to compromise on his creative vision, faulty equipment etc. The resulting film flops in cinemas and Stephen decides to run back to England, but gets caught at the airport with drugs. The narrator of the story, a Pakistani student who seems to be in love with Stephen, finally gets tired of Stephen’s condescension and lies, leaving him to rot in a Pakistani jail.

Julien’s fictional khakas are far from the usual glowing portraits that testify to the rarefied status of literature. They are about flawed people, like the rest of us, burdened by human weaknesses and compromising with their social and economic circumstances. In them, Julien shows, with his characteristic mix of satire and tragedy, that literature is not revealed from the skies or conceived immaculately on the page. It exists in the world. It gets its hands dirty. But its earthly reality is precisely what makes it interesting, what keeps us turning the pages.