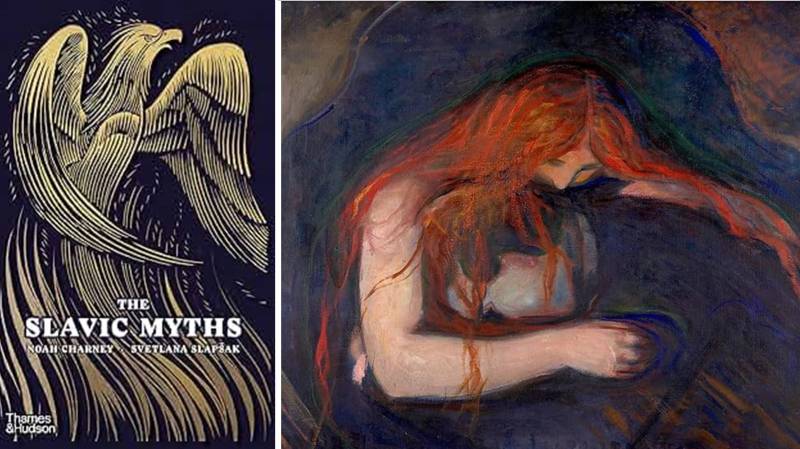

Lewis Carroll’s Alice once famously noted: “What is the good of a book without pictures and conversation?” When it comes to gripping stories, especially fairy-tales she was absolutely correct. Notable art crimes investigative expert Noah Charney and award-winning Balkan studies specialist Svetlana Slapsak have produced a lovely and highly informative volume of Slavic myths, richly illustrated with intriguing black and white pictures throughout. Both writers are based in Slovenia, and it is a credit to them that they have compiled an especially well-chosen collection of not simply stories, but highly informative essays on what makes Slavic myths both timeless and special.

Many people have a vague idea that the origins of werewolves and vampires (which now abound in shows ranging from Supernatural, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and the X-Files to films and books such as those of the Twilight saga) lie in Eastern Europe. Charney and Slapsak provide readable and accurate accounts of how these myths originated in Slavic territory, and go as far as examining a vast compendium of material related to this history that has never been translated into English. They write of artists who worked for decades in order to illustrate Slavic history, noblemen such as barons who wrote about the abovementioned archetypal motifs, underscore the precise definitions of witches, marine and woodland spirits, and triple-faced deities in Slavic culture, and emphatically make one realize how vital werewolves and vampires were to this kind of mythology.

On occasion there was no real difference between a werewolf and a vampire as far as Slavic lore was concerned, although in order to avoid confusion the authors include one story about an undead male vampire who eventually gets put to rest by the diligent and courageous hero of the tale. The image of black butterflies abounding in this account lends a truly Gothic feel to matters, as does the chilling story of a werewolf who harms a trusting child in yet another tale. Although many readers consider the legends of the fearsome witch Baba Yaga and the Firebird to be of vaguely Russian origin, in point of fact they are Slavic to be exact. Even science-fiction author Orson Scott Card was inspired to include the former hag in his book Enchantment.

Not only is the authors’ style of writing eminently readable when it comes to explaining the origins of relatively obscure deities and monsters alike, they retain a beautiful sense of wonder when it comes to retelling the actual stories themselves. Vasilissa the Beautiful communicates with the spirit of her dead mother through a doll in order to cope with a tough life, and the account will bring tears to the eyes even of those who are well past their childhood and youth. Alas, one can hardly call the stories feminist, especially since a reigning queen in one of them gives up her considerable power simply in order to become a wife. However, some of the female characters such as a princess in The Firebird, are memorable not simply because they genuinely help the heroes, but because they note acerbically and humorously that it is hard to understand why men rule the world (since they don’t come across as the sharpest tools in the shed, especially in these tales).

Fairy tales are now meant to be fun in our postmodern, globalized world, although Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm veer more towards the horror genre at times than one might expect. To be perfectly honest, several of the Slavic myths are even darker, but Charney and Slapsak make sure that their own tone remains light, even when the subject matter does not. For example, speaking of the hero who vanquished the vampire in Black Butterfly, they write laconically and slightly hilariously: ‘[The heroine] returned his affection. Her father did not.’ This type of light, elegant touch alleviates the mood in what is otherwise a grim and tragic account of a lonely and misunderstood man who would have been condemned to a life of torment for eternity had not people eventually put him out of his misery. In unearthing the origins of their tales the authors leave no stone unturned, even going as far as to describe rare medical conditions that led to some individuals being unusually hirsute—a point that may have fed into werewolf lore.

I had the pleasure of meeting Noah Charney at a Renaissance conference in Venice, Italy many years ago, and was struck by how modest and down-to-earth he was, in spite of hailing from an elite educational background that involved being schooled at the prestigious Rosemary Choate school and later the Courtauld Institute of Art. At that time he had recently gained fame for writing the engrossing fictional mystery The Art Thief. I enjoyed that so much that I hoped he would venture back into the realm of story-telling, although I understood that his work on exposing art forgeries across the globe was undeniably important. I am delighted to see that destiny has dragged him back to telling a bunch of rollicking good tales. The Slavic Myths is not only worth reading, it will eventually become a pioneering classic over the course of the next few decades. Unlike the forgeries that Noah has exposed over time, this book is inimitable.