The Supreme Court on Thursday issued a comprehensive list of contradictions in the original short and detailed order by a three-member bench of the top court on interpreting Article 63-A of the Constitution and whether a lawmaker voting against the directions of the parliamentary party head result in automatic disqualifications and whether the vote they cast will be counted or not, declaring that the orders of the previous bench were "against the clear language and mandate of the Constitution and are also contrary to the decisions of the larger benches of this court."

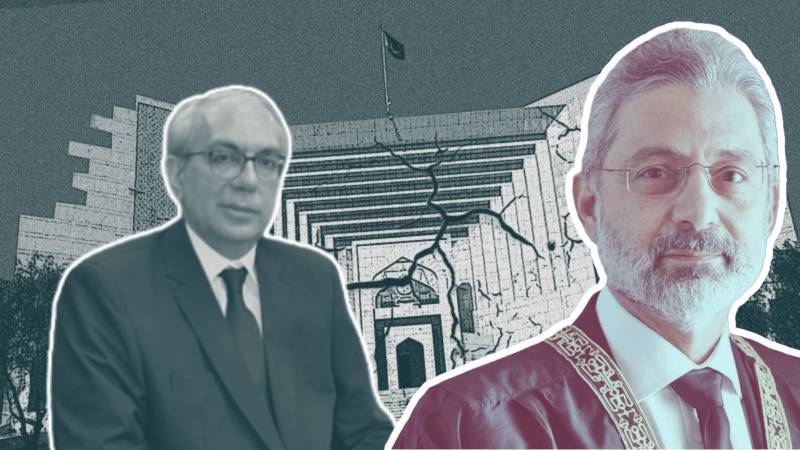

The 23-page decision on the review petition was penned by Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa which addressed not only matters of Constitution, law and precedence on the court's order under review but also associated matters including the way then-President Dr Arif Alvi had sought an opinion from the top court, the context in which a constitutional petition on the matter was filed by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and its former chief, Imran Khan, and the issue of reconstituting the five-member bench after Justice Munib Akhtar refused to participate in it.

Entering political domain

In the unanimous detailed order, the top court noted that judges had attempted to enter into the political domain by divesting the party head of his discretion of proceeding against any party member suspected to have voted contrary to the parliamentary party head's direction or abstained from voting.

The judges, the verdict noted, bestowed it upon themselves to disqualify lawmakers rather than follow the procedures clearly listed in the Constitution.

"The said judges, therefore, had also appropriated to themselves the adjudicatory jurisdiction vesting in the Election Commission, in contravention of clauses (3) and (4) of Article 63. They also took away the right of appeal to the Supreme Court, provided by clause (5) of Article 63-A," it noted.

It added that clauses 1-5 of Article 63-A of the Constitution were unambiguous, clear, exact and manifestly evident that they did not require any interpretation.

"Article 63-A does not state that the votes of any member should not be counted nor that a member who does not vote or abstains from voting contrary to the Parliamentary Party’s direction would automatically be de-seated, but this is what the judges (in the majority) did."

The verdict noted that the clearly enumerated steps in Article 63-A of the Constitution were disregarded and the judges (in the majority) also nullified three separate jurisdictions unequivocally stipulated in Article 63A, which were: (a) the jurisdiction of the party head who may or may not issue the declaration of defection, (b) the jurisdiction of the Election Commission to decide the matter of defection and (c) the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

The court noted that through its judgement, the top court conferred upon itself the party head’s jurisdiction to issue a declaration of defection. The Election Commission was also divested of its jurisdiction, and even the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under clause (5) of Article 63A was effectively abolished. "If a court confers jurisdiction upon itself, it vitiates the fundamental right of fair trial and due process."

"The majority did what was not permissible. Neither a court nor a judge can take away jurisdiction given by the law, let alone that which is conferred by the Constitution."

It added that the three judges could not have invalidated the provisions of Article 63-A, but they effectively did so.

The judgement noted that Justice Ijazul Ahsan, who had a year prior to the verdict under review, had written in a judgement about the dangers of ‘reading something into the Constitution’, which would have ‘disastrous consequences’. But he seemed to have disregarded his advice in the judgement on Article 63-A.

The verdict noted that the majority’s judgment appeared to substitute its wisdom with that of the makers of the Constitution and adopted a course not followed anywhere in the world.

"Instead of a constitutional or legal basis, the majority’s judgment has a surfeit of moralisms and non-legal terminology, such as healthy (41 times), unhealthy (5 times), vice (9 times), evil (8 times), cancer (8 times), menace (4 times), etc."

It added that the majority’s judgment also reflects a complete distaste for parliamentarians (in paragraph 106) as it proclaims that in the history of Pakistan and its Parliament, only once did a parliamentarian come close to becoming a ‘conscientious objector who took the path of defection and de-seating under Article 63-A.’

"The expression of such contempt for politicians and parliamentarians is regrettable. Let us not forget that Pakistan was achieved by politicians who had gathered under the banner of the All India Muslim League and its Quaid (leader), MA Jinnah, who strictly followed the constitutional path."

Seeking opinion or shaping response?

The top court noted that while the Constitution allows the President to seek opinions on questions of law from the top court, the manner in which the President posed the questions at a time when a vote of no confidence had already been submitted in the Parliament, meant that the President was entering the political fray and that he was "expounded what he considered to be a moral issue, gave his own opinion and wanted this court to concur with it."

The court noted that the "Sami Ullah Baloch decision was overruled by a larger seven-member bench of this court in the case of Hamza Rasheed Khan v Election Appellate Tribunal (2024 SCP 65, on the Supreme Court’s website) wherein it was held that lifelong disqualification is not prescribed by the Constitution, and if this was done it would by ‘reading into the Constitution’, which was not permissible."

Are opinions binding?

The top court recalled: "This court has held that the ‘Opinion of the Supreme Court is just opinion with explanation on the question of law and is not of binding nature and it is up to the President or the federal government to act upon it or not."

It further added that an opinion is also not executable, however, an order passed by the Supreme Court (on a petition filed under Article 184(3) of the Constitution) is binding (Article 189 of the Constitution), and it is also executable.

If a decision in terms of Article 189 contradicts the court's opinion under Article 186, the court's decision and not the opinion will prevail.

It further noted that while a review of any judgement or order can be sought under Article 188 of the Constitution, the law does not state whether a review of an opinion can be sought.

The court noted that in this instance, where the top court also fixed for hearing a petition along with the opinion sought by the President, a joint short order was issued by the majority whereby the short order stated it was disposing of matters filed under Article 186 and Article 184(3), it "is to be read and understood as a simultaneous exercise of (and thus relatable to) both the jurisdictions that vest in this court under the said provisions, read also in the case of the latter with the jurisdiction conferred by Article 187.’ Therefore, we have no option but to hear and decide them in this CRP.

Associated context of case

The judgement noted that even though no PTI member voted against party lines but was still unsuccessful in saving then Prime Minister Imran Khan from being ousted as they lacked sufficient votes, a constitutional petition was filed by PTI member Babar Awan, and represented by senior lawyer Syed Ali Zafar, with the prayer that it be, "declared any sort of defection would amount to imposing a lifetime ban from contesting elections, in the interest of justice."

"Apparently, this, petition was filed for another purpose, which was with regard to the election of the Chief Minister of the province of Punjab," it said, adding that the top court's Registrar ordered for the petition to be fixed with the other Constitution petition and Presidential reference, even though the latter had undergone six hearings. The matter was decided on May 17 after another ten hearings by then-Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial, Justice Ijazul Ahsan and Justice Munib Akhtar.

The court went on to note that when Imran Khan was voted out of the office of Prime Minister, it was done without the vote of a single PTI member against him, and since all those who wanted to vote had voted, the Constitution petition subsequently filed by the PTI and the questions sent for opinion in the Reference were rendered moot and irrelevant, and these matters became infructuous.

However, and inexplicably, on April 14, 2022, another Constitution Petition was filed by PTI and Imran Khan even though no one from PTI had voted against Imran Khan’s premiership. Apparently, it was filed [pre-emptively] to attend to matters in the Punjab Assembly.

"The short order was passed in matters which had become infructuous but it still decided that if votes were cast against the Parliamentary Party’s direction these will not be considered and this ‘would [also] constitute a declaration of defection’," the top court noted adding that the short order passed by the top court effectively invalidated Hamza Shahbaz’s election as the Punjab Chief Minister even though this was not the subject of the petitions.

The votes cast in Hamza Shahbaz's favour by PTI members were discarded, and they were also de-seated, but the top court did not issue them notices on the matter; in the said three matters, their fundamental right of fair trial and due process, guaranteed by Article 10-A of the Constitution, stood nullified.

Another consequence of the court's majority judgment would be that once a prime minister and chief ministers are elected, they can never be removed either by their party or by the majority membership of the concerned assembly.

"Nothing can be more undemocratic; the majority’s judgment has opened the way to transform the leader of a political party into a dictator, simply because the party’s leader can never be challenged."

Addressing Justice Akhtar's absence

The detailed judgement also addressed the absence of Justice Munib Akhtar, who was the author judge of the original verdict of the three-member bench of the top court. Zafar had also contested the constitution of the bench for allegedly falling afoul of provisions of the Practice and Procedure Act and then the subsequent reconstitution of the bench.

The judgement explained that when the five-member larger bench was originally constituted, it did include Justice Akhtar. However, the judge later expressed his inability to attend hearings. The verdict did not mention how, in his letter addressed to the Registrar of the top court, Justice Akhtar categorically stated that his absence from the bench should not be misconstrued as his recusal from the case.

The verdict added: "Justice Munib Akhtar’s stated inability [to attend the five-member bench] was not because the timings of the two benches (the three-member bench he was part of but had completed its work by 11 am) clashed; in any event the work of a larger bench always takes priority."

It further said that the remaining four members of the bench did not continue hearing the petition, and instead, an effort was made to "ensure" Justice Akhtar's participation on the bench through a written request.

"However, the request was not accepted by Justice Munib Akhtar who, through his letter dated September 30, 2024, repeated his inability to do so. Therefore, his lordship was substituted on the bench with another judge of the Supreme Court by the [bench fixing] Committee. Learned Syed Ali Zafar conceded that the law (Ordinance XXVI of 2024) had to be followed."

The court also dismissed the arguments that the petition had been hurriedly fixed for hearing out of turn by noting that it had been filed over 27 months ago.

"The review jurisdiction is created by the Constitution, and it may be invoked in respect of an order already made or judgment already pronounced; therefore, by its very nature, a review petition should be fixed for hearing earlier than other cases," it said. It added that this is done because the judges who had passed the order or judgment may not be available later. In this case, Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial retired and Justice Ijazul Ahsan resigned.

The top court noted that the matter of fixing the review petition came up before the bench-fixing committee during its 18th meeting held on August 1, 2024, when Justice Munib Akhtar was still its member and he and the senior most (puisne) judge did not agree with the Chief Justice to fix it ‘for hearing in the next ten days’ nor agreed with the bench proposed by the Chief Justice (Committee minutes are available on the Supreme Court’s website).

"Neither Justice Munib Akhtar nor the most senior (puisne) judge could arrogate to themselves the power to nominate the third member on the Committee, which the law had granted to the Chief Justice, nor could insist that Justice Munib Akhtar be on the Committee. Whether it behoves a judge to insist on being on the committee, or to be on any committee, we need not dilate upon."