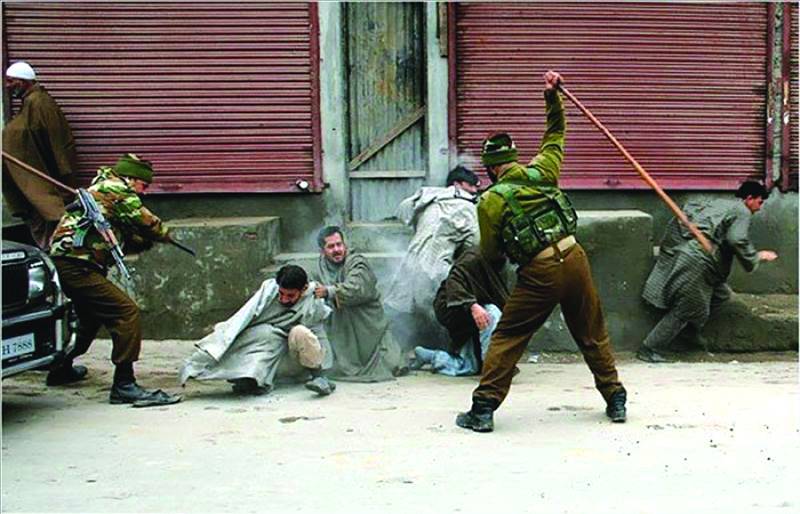

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an independent international court that tries persons accused of the most serious crimes of international concern, namely, the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. The commission of these crimes in the Indian-held Kashmir warrants an independent investigation and a trial before the ICC as a court of the last resort.

Genocide and crimes against humanity are on the rise in the IHK, therefore, this opinion focuses on these two crimes. Article 6 of the Rome Statute, 2002 (Statute), describes ‘genocide’ as acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group - such as killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part [...].Article 7 of the Statute defines ‘crime against humanity’ as “a widespread or systematic attack against any civilian population, with intention of murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or forcible transfer of population, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law, torture, rape […] persecution against any identifiable group or collectively on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, enforced disappearance of persons, the crime of apartheid and other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or mental or physical health.”

As per Article 5 of the Statute, genocide and crimes against humanity fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC. Essentially, there are three ways to invoke the jurisdiction of the ICC: referral of a situation by a state party; referral of a situation by UN Security Council; and the prosecutor’s initiative on the receipt of information by an intergovernmental or non-governmental organization.

Under Article 14 of the Statute, “a state party may refer to the prosecutor a situation in which one or more crimes within the jurisdiction of the court appear to have been committed requesting the prosecutor to investigate the situation to determine whether one or more specific persons should be charged with the commission of such crimes.” Under Article 15 (proprio motu), the prosecutor may initiate investigations on their own initiative based on information on crimes which fall within the jurisdiction of the court under Article 5. Under Article 15, one or more of such crimes (the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression) may be referred to the prosecutor by the Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations.

As Pakistan is not a party to the Rome Statute, it cannot directly invoke the jurisdiction of the ICC under Article 14. The option to refer the situation in IHK through the UN Security Council is there but it may be blocked by any permanent member of the Security Council. However, the prosecutor may initiate investigations on the situation in IHK based on information received by any source i.e. intergovernmental or non-governmental organization.

However, a state against whom the prosecutor invokes investigation on own initiative can object to the initiation and the admissibility of the proceedings on the grounds that the accused are being tried by a state’s national courts as they have jurisdiction or the investigation for the commission of alleged crimes is being conducted by national authorities. Article 17 (1) of the Statute provides that, “the court shall determine that a case is inadmissible where the case is being investigated or prosecuted by a state which has jurisdiction over it unless the state is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution; that the case has been investigated by a state which has jurisdiction over it and the state has decided not to prosecute the person concerned unless the decision resulted from the unwillingness or inability of the state genuinely to prosecute; that the person concerned has already been tried for conduct which is the subject of the complaint.” Under Article 18 (2), at the request of the state, the prosecutor may defer to the state’s investigation of those persons allegedly involved in the commission of the crimes. Article 19 further provides for objection to the jurisdiction of the court or the admissibility of a case. As per Articles 81 and 82 of the statute, the decision of the pre-trial chamber (as to the authorization of investigation) and the trial-chamber (as to the acquittal or conviction of the accused) can be appealed against following the rules of procedure and evidence such as error of fact or error of law.

Thus, to build a strong case for the commission of serious crimes such as the crime of genocide and crimes against humanity, the procedural and evidentiary requirements under the framework of the Rome Statute must be satisfied by the referring organization. India is unwilling to investigate and conduct an impartial trial of those who are engaged in the crimes in Indian-held Kashmir. The so-called investigations and trials by Indian officials, if any, are a farce, and part of the strategy to protect offenders from the consequences of their crimes. Therefore, the ends of justice and the norms of international law require an impartial investigation and independent trial of accused before the ICC.

The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

Genocide and crimes against humanity are on the rise in the IHK, therefore, this opinion focuses on these two crimes. Article 6 of the Rome Statute, 2002 (Statute), describes ‘genocide’ as acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group - such as killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part [...].Article 7 of the Statute defines ‘crime against humanity’ as “a widespread or systematic attack against any civilian population, with intention of murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or forcible transfer of population, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law, torture, rape […] persecution against any identifiable group or collectively on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, enforced disappearance of persons, the crime of apartheid and other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or mental or physical health.”

As per Article 5 of the Statute, genocide and crimes against humanity fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC. Essentially, there are three ways to invoke the jurisdiction of the ICC: referral of a situation by a state party; referral of a situation by UN Security Council; and the prosecutor’s initiative on the receipt of information by an intergovernmental or non-governmental organization.

Under Article 14 of the Statute, “a state party may refer to the prosecutor a situation in which one or more crimes within the jurisdiction of the court appear to have been committed requesting the prosecutor to investigate the situation to determine whether one or more specific persons should be charged with the commission of such crimes.” Under Article 15 (proprio motu), the prosecutor may initiate investigations on their own initiative based on information on crimes which fall within the jurisdiction of the court under Article 5. Under Article 15, one or more of such crimes (the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression) may be referred to the prosecutor by the Security Council acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations.

As Pakistan is not a party to the Rome Statute, it cannot directly invoke the jurisdiction of the ICC under Article 14

As Pakistan is not a party to the Rome Statute, it cannot directly invoke the jurisdiction of the ICC under Article 14. The option to refer the situation in IHK through the UN Security Council is there but it may be blocked by any permanent member of the Security Council. However, the prosecutor may initiate investigations on the situation in IHK based on information received by any source i.e. intergovernmental or non-governmental organization.

However, a state against whom the prosecutor invokes investigation on own initiative can object to the initiation and the admissibility of the proceedings on the grounds that the accused are being tried by a state’s national courts as they have jurisdiction or the investigation for the commission of alleged crimes is being conducted by national authorities. Article 17 (1) of the Statute provides that, “the court shall determine that a case is inadmissible where the case is being investigated or prosecuted by a state which has jurisdiction over it unless the state is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution; that the case has been investigated by a state which has jurisdiction over it and the state has decided not to prosecute the person concerned unless the decision resulted from the unwillingness or inability of the state genuinely to prosecute; that the person concerned has already been tried for conduct which is the subject of the complaint.” Under Article 18 (2), at the request of the state, the prosecutor may defer to the state’s investigation of those persons allegedly involved in the commission of the crimes. Article 19 further provides for objection to the jurisdiction of the court or the admissibility of a case. As per Articles 81 and 82 of the statute, the decision of the pre-trial chamber (as to the authorization of investigation) and the trial-chamber (as to the acquittal or conviction of the accused) can be appealed against following the rules of procedure and evidence such as error of fact or error of law.

Thus, to build a strong case for the commission of serious crimes such as the crime of genocide and crimes against humanity, the procedural and evidentiary requirements under the framework of the Rome Statute must be satisfied by the referring organization. India is unwilling to investigate and conduct an impartial trial of those who are engaged in the crimes in Indian-held Kashmir. The so-called investigations and trials by Indian officials, if any, are a farce, and part of the strategy to protect offenders from the consequences of their crimes. Therefore, the ends of justice and the norms of international law require an impartial investigation and independent trial of accused before the ICC.

The writer is an advocate in the Supreme Court of Pakistan.