With its manpower and resources, the Pakistani Army is consistently responding to natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods. Many of us who have served in the army have participated in 'Flood Fighting’ duties, and I am no exception. However, my first experience of serving on such duties was undoubtedly distinctive.

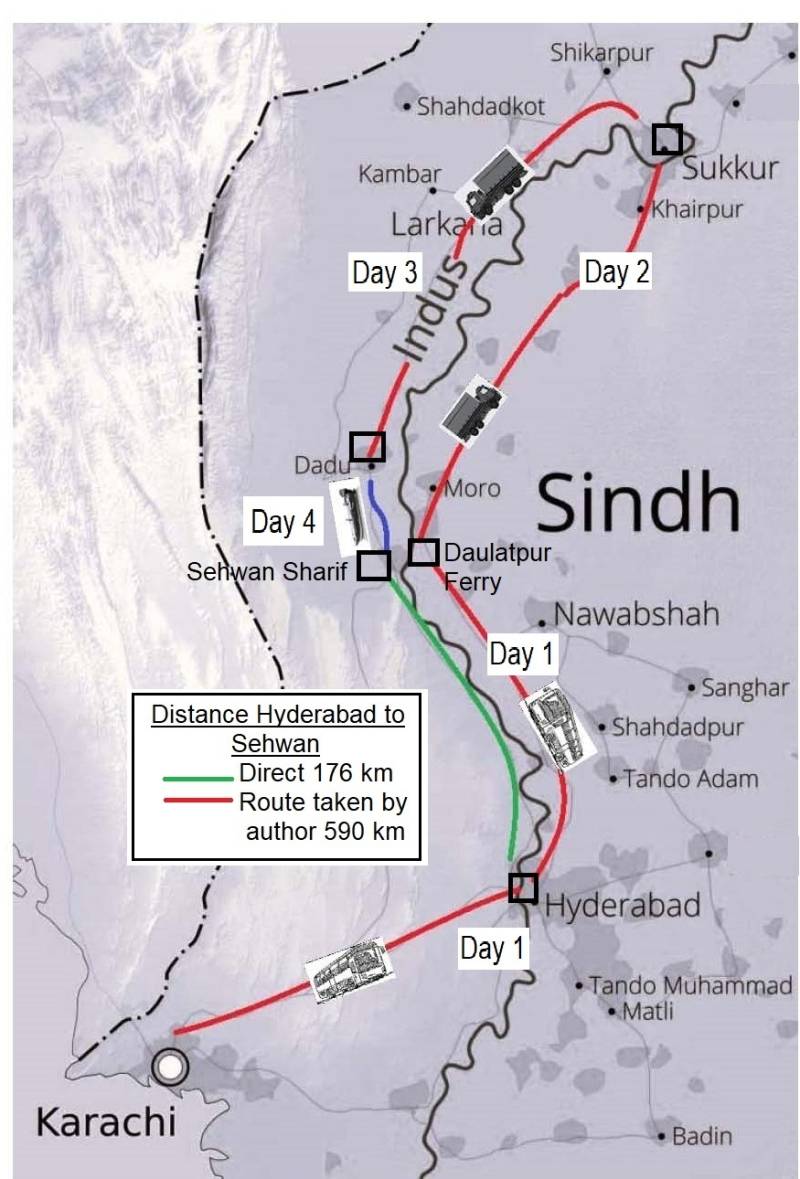

In 1976, my regiment was stationed in Malir. Upon my return in August, following an attachment at PMA, I was told that it had relocated to Sehwan Sharif for 'Flood Fighting' operations. Sehwan is a small historic town located on the west bank of the Indus, 130 km upstream from Hyderabad and home to the shrine of one of the greatest Sufi saints, Syed Muhammad Usman Marwandi, commonly known as Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. Orders had been issued for all returning personnel to make their way to Sehwan. “How?” I asked the Duty Clerk. “Sir. We will put you on a bus to Hyderabad from where you will change for a bus to Sehwan. You will be there by the evening.”

As a cadet and young officer, I had travelled by bus many times and the journey sounded easy. Little did I know that it would turn into a gruelling five-day expedition, involving buses, trucks, and even boats, before reaching our destination.

Fortunately, that evening I was joined by a friend Capt Muhammad Hassan, who had returned from leave. He was one of my squadron officers and a good companion to travel with because he was pleasant-mannered and dependable. Since it was Ramzan, we caught an early bus after Sehri and arrived at Hyderabad by 10 am only to be told that the road to Sehwan along the west bank of the Indus had been breached by the swelling waters of the river. “How do we get to Sehwan?” we asked a helpful bus driver at the bus stand. “Sain,” he addressed us in a form common to Sindh, “I am driving to Sukkur and will drop you off at Daulatpur, from where you can take the ferry across the Indus to Sehwan.”

As the bus crossed the 600-metre-long bridge over the Indus at Kotri, for the first time I saw the power of the great river in spate. However, it didn't occur to us that under these conditions, no ferry would dare to make the crossing. Four hours later, when we disembarked at the small market town of Daulatpur, it started to drizzle. We asked directions for the ferry from a shopkeeper, and deliberately or otherwise, he did not mention that it was not plying. Lugging our suitcases that felt heavier at every step, we trudged along a wet and slippery flood embankment that led to the loading ramp. A kilometre ahead, we met a farmer who had the decency to tell us that the ferry had stopped plying three weeks ago. Despondently, we trudged back to the main road and were at a loss for what to do. It was close to 4 pm and we were tired, wet and hungry – and no bus heading either way showed any willingness to stop for us.

However, the angel of mercy was watching over us. Suddenly Hassan spotted a soldier in uniform standing in front of a Tandoor. The sight of a soldier suggested the presence of more military personnel, possibly a detachment of a military unit. We were saved. He took us to a government rest house across the road, where an engineer detachment had halted for the night. The JCO in charge informed us that he was taking three requisitioned civilian trucks loaded with boats and men to Sehwan via Sukkur. It was a stroke of luck we couldn't have anticipated. We were treated to Iftar cum dinner and the patter of rain lulled us into an exhausted sleep on the verandah of the rest house.

We departed after Sehri, with the two of us sitting next to the driver on a seat that was no more comfortable than a bench. Compared to the bus, the truck was painfully slow and our boredom was occasionally relieved by the antique gear lever. It was a floor shift and whenever the truck hit a bad pothole, the lever popped out of its socket and the truck went into neutral drive. I am fairly mechanical-minded but could not figure out how the two were related. Each time this happened, the driver pulled to a stop, pushed the lever back into the gearbox, engaged the gear, and accelerated. The long but otherwise uneventful leg of 180 km to Sukkur took all day and the early part of the night, but before we crossed over the Sukkur Barrage, our small convoy halted at a roadside hotel for Iftar. There was an anti-Punjabi wave in the province since Bhutto had become prime minister and the Sindhi owner refused to serve us. “The hotel for Punjabis is further ahead,” he said sourly.

By boat, we followed the line of half-deep electric poles that indicated the alignment of the road

It was close to midnight when we drove into Sukkur and stopped opposite a petrol pump. We required refuelling and since the civilian trucks had been requisitioned ‘In Aid of Civil Power,’ they could be refuelled on written authorisation obtained from the office of the Deputy Commissioner. However, given the late hour, no office would be open and we were contemplating pooling whatever money we had to keep going, when the angel of mercy was again kind to us. A convoy of five military and civilian trucks loaded with soldiers and stores pulled into the pump. It was commanded by a major who was taking the staff and personnel of a brigade HQ that had been detailed to fight floods in the Dadu District. He had the necessary authority to refuel and agreed to also top up our vehicles. By now, it was well past midnight and we were tired but decided to head out of Sukkur and stop enroute to prepare Sehri and rest.

Having caught a few hours of sleep at a vacant rest house of the Irrigation Department, we set off on the last leg of 280 km. The day was hot and humid and while the traffic was light, the road was bad. But thank God the driver had repaired the gear lever, and it no longer popped out. The monotony of sitting in a truck that seldom achieved more than 55 km per hour was soul-destroying, and the uncomfortable seat denied us any hope of sleeping. We were both regular smokers and through sheer boredom smoked twice as much as we usually did. To make things worse, the engine of the truck behind us started overheating and we spent a couple of hours with a roadside mechanic to have the radiator repaired. This was turning out to be a journey of horrors. It was our third day on the road and we seemed to be getting nowhere.

That evening we found no Rest House, and slept in a roadside ‘hotel’ in the open on charpoys (a light bedstead) that we washed with petrol to clear out the bed bugs. There was some disturbing news from a truck driver who was on his way from Dadu, which was 50 km short of Sehwan. According to him, floodwaters were encroaching upon the town, and the main road had been severed. The next morning when we arrived in Dadu, we found that the information was partially correct. The flood waters were still 15 km south of Dadu but the road to Sehwan had been severed a few days ago. It felt like we were back in the same predicament that we faced when our journey began.

Fortunately, the angel of mercy had not forsaken us. I inquired with the JCO about his plan and he responded with confidence, "In the afternoon, we will unload the boats at the water's edge, attach the outboard engines, and conduct tests. If all is well, early tomorrow morning we will journey to Sehwan in the boats." The notion of traveling by boat had not crossed our minds, given our training in the armoured corps rather than military engineering. That evening, we relaxed with the officers of the brigade HQ who had travelled from Rahim Yar Khan and ate decent food in their field mess. We were graciously provided a room in the Rest House where they were also lodged, affording us a much-needed opportunity for a bath. Through conversations at the brigade HQ, we learned that while the Dadu District itself had not borne the brunt of the Indus River's impact, heavy rains in the hills bordering Balochistan had caused water to surge into the district, rendering the road impassable.

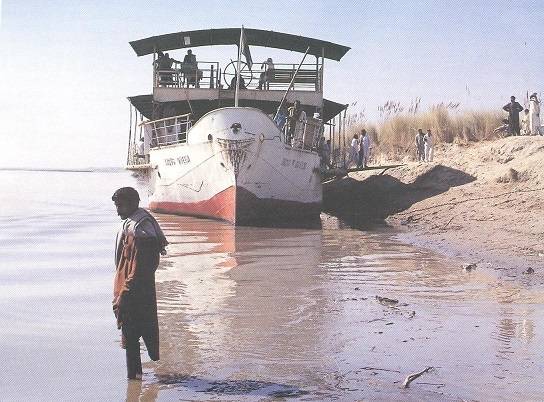

Early the next morning, a jeep dropped us off where the boats were moored and ready to depart. Ahead of us, as far as the eyes could see, was water that varied in depth. In quite a few places, the soldiers had to row or get into the water to push the boats, because it was too shallow to run the Evinrude outboard motors (OBMs). The Evinrudes were manufactured in USA and were the best that money could buy – but this particular model did not have enough power to propel the military boats that we were using against a strong current. Nevertheless, at this point the flood waters were calm and we were averaging about three knots. The JCO estimated that we would be in Sehwan by the afternoon and our long torturous journey through Sindh seemed to be coming to a close without a serious mishap. Or so we thought.

If the journey till Dadu had been a test of endurance, today would turn out to be a test of nerves. We followed the line of half-deep electric poles that indicated the alignment of the road, and 500 metres to our left was an embankment of the railway running along the west bank of the Indus. The brigade HQ at Dadu had told us that this embankment was hindering the flood water from the foothills flowing into the river. The culverts on the embankment were insufficient and the water was building up behind it causing floods in the Dadu District. We managed to bypass the few villages that lay along the road but three hours after setting out, a large village appeared that was sitting high on a ridge perpendicular across our path.

The engineer boats were flat-bottomed skiffs developed in the Second World War. Constructed of plywood, they weighed over 500 kg and required eight to ten men to lift. We didn’t have enough hands to carry the boats, the OBMs, fuel, and all the rest over the ridge. We tried to find a passage around the western shoulder, but the ridge just carried on. We then reversed direction towards the railway embankment and a bridge under which the water was flowing. Hassan and I conferred that if got through to the other side of the railway line our boats could resume heading for Sehwan.

Suddenly, the boat was being propelled faster towards the bridge by an increasingly strong current. As it loomed closer, I was alarmed to see that the gap between its steel girders and the water was not more than a metre or so and maybe too small for the skiffs to pass through safely. Suddenly, the boat accelerated, propelled swiftly towards the bridge by an increasingly strong current. As the bridge loomed closer, my alarm grew when I realised that the gap between its steel girders and the water was not more than a metre or so, potentially too small for the skiffs to pass through safely. “Kishti ko wapis moro” [Turn the boat around], I shouted to the soldier manning the OBM. He gunned the engine and tried to get out of the current but the engine didn’t have the power and we were dragged towards the bridge. I just had time to shout “Kishti ko seedha karo” [Straighten the prow of the boat], and ducked as we were propelled under the bridge at an alarmingly fast speed. The readers may have experienced a sudden and unexpected event when things are totally out of their control – and for me, this was one such occasion.

Loaded with six men, luggage, fuel, and engineer stores, the skiff rode low in the water, with only a foot above the waterline but the OBM extended another foot and a half. As the skiff passed under the first girder, there was a mere foot to spare, but the OBM collided with it, producing a loud 'bang!'. I didn’t hear the sound of an impact as the boat passed under the second girder, and I anxiously looked back, fearing the OBM had been dislodged into the water. A wave of relief washed over me as I saw it still attached, sputtering along, though its cover had vanished. Even after 45 years, the memory of those moments remains vivid—the approach to the bridge, the massive steel girders inches above us, and the resonating sound of the OBM cover striking the girder.

For a minute or so, we sat in shocked silence as the skiffs drifted along with the current in an endless sea of brown—the floodwaters of the mighty Indus. However, we were a good 10 km from the river's main channel, and as long as we maintained a course near the railway embankment, we could safely reach Sehwan. The other boats had fared better and now that we were in deeper water with a minimal risk of the propeller striking submerged objects, we increased our speed, and all three boats raced along in parallel.

Gradually, a large mound emerged on the horizon—the remnants of Kafir Qila in Sehwan, also known as Alexander's Fort. We had finally reached 'home.'