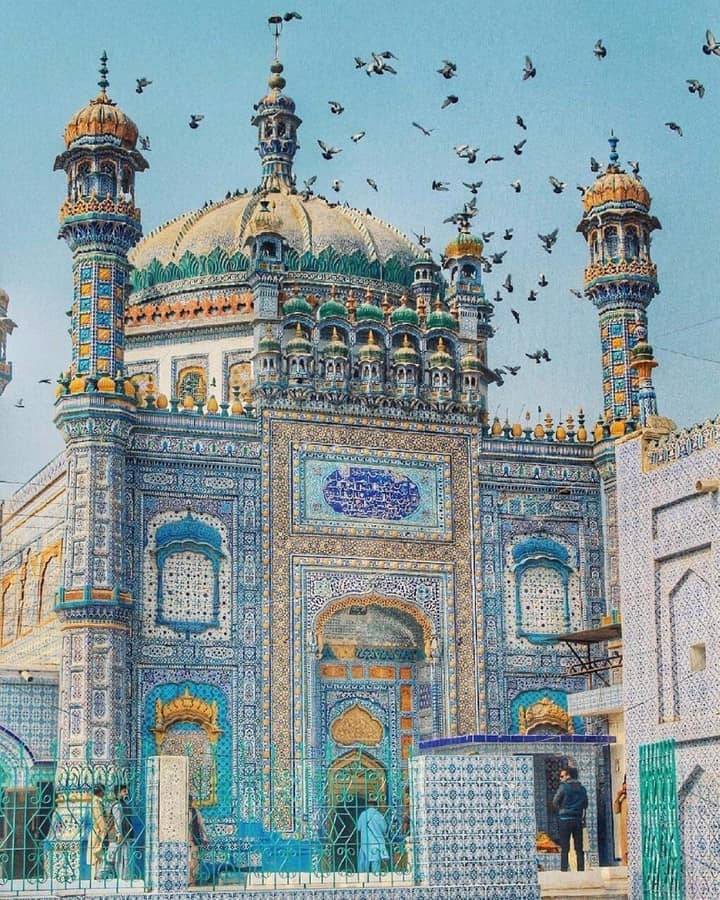

In recent years, new socio-religious movements and leadership have emerged across South and East Asia, often drawing inspiration from more mystical or Sufi strands of religious tradition. These centuries-old Sufi influences continue to shape contemporary socio-religious dynamics in the South Asian Subcontinent.

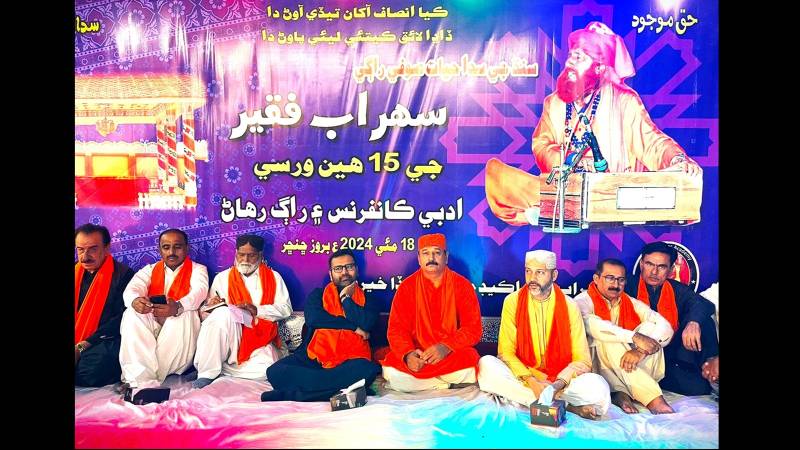

To explore this intersection of Sufism and modern development work, I recently had the opportunity to interview Dr Khadim Dahot, who manages the Sewa Development Trust Sindh (SDTS) in the Khairpur Mir region of Sindh, Pakistan. As a Sufi practitioner himself, Dr Dahot shared his perspectives on how Sufi traditions inform his approach to community development.

Question: How do you introduce yourself?

Answer: I carry multiple identities – I‘m a Sindhi with a rural background, I’m a social activist and researcher, and importantly, I’m also a Sufi teacher. But, my name is Khadim Dahot and I hail from Khairpur Mirs.

Q: You also head a development organisation, the Sewa Development Trust Sindh. What makes your approach distinct from traditional NGOs?

A: At SDTS, we take a markedly different perspective compared to many conventional development actors. For instance, we do not blame the poor for their own suffering - we recognise that poverty is the outcome of flawed policies, misplaced priorities, and a lack of political will to uplift the marginalised. Moreover, our work is grounded in an understanding that the poor are not isolated individuals, but are embedded within the rich tapestry of village-level social and cultural systems. We do not idealise the poor, but acknowledge that they are integral members of society, with both positive and negative practices. This nuanced perspective, shaped by Sufi traditions of holistic wellbeing and community solidarity, sets us apart from many conventional development approaches that tend to view the poor through a more limited, individualistic lens.

"In Sufi practice, trust is required before embarking on the path. In the material world, trust has administrative, legal, and financial forms, but in Sufism, it has spiritual forms, layers, and zigzag paths"

Q: Can you share some examples from your work that illustrate this distinctive Sufi-inspired approach to community development?

A: Sure. In our programs, we make a concerted effort to leverage the emotional, cultural, and social support systems that already exist within rural communities. Rather than imposing external solutions, we seek to empower and build upon the inherent resilience and agency of the people. For example, in one of our villages, we worked closely with local women’s groups to revive traditional handicraft skills and create sustainable livelihood opportunities. By tapping into existing social networks and cultural practices, we were able to generate tangible economic benefits while also strengthening communal bonds and a sense of collective identity. In another initiative, we collaborated with religious scholars and Sufi leaders to raise awareness about issues such as environmental conservation and gender equity, framing these modern concerns within the broader context of Sufi teachings on harmony, compassion, and social responsibility. This approach has proven to be more effective and resonant than top-down, technocratic interventions.

Ultimately, our Sufi-inspired development model emphasises the importance of integrating spiritual, social, and material dimensions of human wellbeing. It is an approach that seeks to empower communities from within, rather than imposing others solutions. This is how we strive to make a meaningful and lasting difference in the lives of the people we serve.

Q: In the 1990s, Sindh in general, and Khairpur Mirs in particular, has seen vibrant grassroots NGOs or popularly known as Community Based Organisations. How do you retrospectively look at that local movement?

A: You have rightly pointed out. If I may look at the movement from a long-term perspective, I would say that donor-supported initiatives first started in the Northern Areas and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. However, in Sindh and even in Balochistan these new approaches of the community development reached in the 1990s. The organisational or even strategic ideas came from Rural Support Programs, the NGO Resource Center, Strengthening Participatory Organisations, the Trust for Voluntary Organisations, and even the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). On the other hand, South Asia Partnership, Oxfam, and Strengthening Participatory Organisation supported the small, untested ideas of the community organisations. However, in the case of the Khairpur Mirs, an innovative capacity-building program was implemented by the NGO Resource Center (a Project of Aga Khan Foundation), which, as I have learned from my seniors, was called a “non-funding approach” to capacity building. We should not be hesitant to acknowledge that the active CBO movement was considerably reliant on external funds, and gradually, their activities became more financially intensive. Over time, as donor policies changed, the once-considered vibrant movement shrank and gradually became inactive. On the other hand, the CBO organisations of the Khairpur Mirs remained active and survived - at least a countable number of CBOs continued their activities.

Q: What were the reasons?

A: Each group or organisation might have gone through different challenges and come up with varied strategies to survive and continue. However, some common practices or survival approaches among them were: manageable areas of work (say, a union council or a cluster of villages), a volunteer-based structure, low administrative costs, and being embedded within the community (most CBO offices and leaders were from the same villages). Of course, there was also a supportive and enabling environment for these local initiatives from the various sections, particularly the social welfare department, NGORC and the district administration.

Q: And now, what changes have you seen?

A: A retrospective review suggests that the rural areas have seen new infrastructure, new communication technology, and increased mobility, particularly of women. However, two simultaneous developments are also observed. First, the number of violent cases against women, minorities, and children has increased. Sadly, the funds for human rights or rights-related interventions have been reduced, and the government has also discouraged the kind of interventions that could help create a more refined citizenship.

Q: You have travelled a lot. What common character have you noticed among the people of the developed world?

A: To be honest, I do not have a deep understanding of Western society, as my encounters have remained relatively short. However, what I have observed is that people are generally law-abiding, have a sense of urgency, and follow agreed-upon rules. None of them seek shortcuts, privileges, or abuse or use of discretionary powers. All of them are treated equally before the law.

Q: What other contrasts or inspiring ideas have you observed?

A: I have noticed that there is a sense of equality, with all citizens being treated equally. I have also noted from their conduct that trust prevails at the societal level.

Q: As a Sufi practitioner, 'trust' has also been discussed in Sufi traditions. Could you elaborate on this?

A: Trust is quality or character of humans. In other words, it is the highest level of confidence in a fellow human being. We all encounter many events in our daily lives, such as shaking hands with a new person or accepting tea or a glass of water from a stranger. But, we never doubt. However, in the Sufi tradition, trust is a process, where one has to trust the path and accept its sufferings and challenges. In Sufi practice, trust is required before embarking on the path. In the material world, trust has administrative, legal, and financial forms, but in Sufism, it has spiritual forms, layers, and zigzag paths - as is the case also with the teachings of the Gurus.

Q: What are the areas where Sufi practices can support development?

A: First, we should not segregate or isolate the Sufi ideas from societal challenges or social justice. I have learned through my own experiences that Sufi ideas can help us value social justice, promote harmony, encourage environmental awareness, facilitate individual positive transformation, and appreciate people’s experiences related to the same phenomena.

Q: In Sufi teachings or trainings, the basic approach is to share stories, and such types of fables or folk stories are found in every culture, including Sindhi culture. Could this method be applied in motivational sessions in the development sector?

A: Surely, but we should be very clear that while the story’s content will be the same, but it could be interpreted differently. In motivational sessions, these stories could be shared as examples. These stories would help participants frame the situation and relate to their roles.

Q: What is your message as a social activist and Sufi practitioner?

A: I have learned that we should value peoples’ perspectives, allow them to experience, and guide them if they ask or demand. Another thing I have learned is that society does not operate in a segregated way; it obeys some general set of rules. In this regard, our role as social activists or Sufis is to be vigilant, to ensure that these rules are not tampered with and that powerful individuals or groups are not encroaching on the areas of the weaker sections. In all these situations, we should be whistleblowers and guardians.

Q: Thank you very much for sparing the time for this wonderful interview.

A: I am grateful to have been interviewed on these topics!