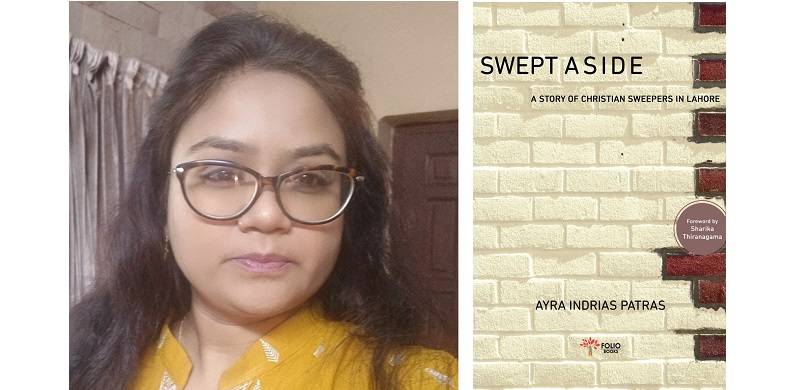

The sweepers are a common feature of increasingly urban Pakistan but very few of us have ever found the need or desire to write their stories, their dreams, desires and everyday struggles. This new book by Dr Ayra Indiras Patras is an attempt to collect these stories and make them accessible to a larger audience. Swept Aside is not a monograph but also a narrative of the neglect and abandonment forced upon the community of sweepers by both state and society of Pakistan. It tracks their lives to first comprehend and then show the hopeless situation of these communities – notwithstanding the changing social, political, and economic arrangements in Pakistan. The book is published by Folio Books, an increasingly inspiring young publication house located in Lahore.

Dr Ayra should be congratulated on writing a well-rounded book that weaves together a complex and multi-axial narrative of discrimination, exclusion and coloniality affecting the most downtrodden group of female sweepers belonging to Churha castes. The most important feature of the book is the flow of the narrative and the speed with which themes and events unfold. It makes for a captivating read and made it hard to leave as soon one starts reading it. Some parts of the book (chapter 2) discuss academic theory but the way it has been articulated by the author even a non-academic reader can also enjoy reading it. One should congratulate not only the author but also the editors of the book who have done an incredible job of improving the readability. The title cover is very original and illustrates the exclusion in an artistic way. The book is published by Folio books could be order from their online web page. It could be ordered online from the website of the publisher.

The Book is divided into four well-written chapters dealing with the place of Christians, discursively and socio-politically, in the master narrative and realpolitik of the Pakistani state. The second chapter is the most important, insightful and moving commentary on the baggage of identities and how they overwhelm individuals, families and generations of Churha communities seen from the lens of its female members. It dives into history, spatiality and gendered reality that reinforces a burden and inhibits the political agency of christian men and women workers. The third chapter mainly documents the indignity and precarity attached to neoliberal forms of employment how it directly undermines the safety of Christian women workers and many a time led to sexual harassment and even physical violence at the workplace.

The last chapter is about the dream of social mobility shared by Christian girls and how they turn sour. It uses case studies of working women who were able to get into more ‘respectable’ professions and still could not find themselves out of the zone of exclusion. It also documents cases of those women who choose to convert for improving social acceptability but actually become victim of double oppression. They remain a Churha even after becoming Muslim, wrongly believing that egalitarian ethos of Islam will help them in achieving dignity, and in the process also squander the support mechanism of family and community. Another contribution of this chapter is to bring out to light the role of colonial laws like, 1865 Christian marriage Act, in undermining the agency of christian women from lower castes. The law only allows the legal dissolution of marriage if one partner claims and prove that her spouse has done adultery. It leads to legal battles and public mudslinging on each other’s character by creating flimsy grounds. These structural realities of poverty and untouchability put women belonging to churha castes in an unending cycle of exclusion.

The book has made some important contributions to the academic understanding of exclusion, marginality and gender studies. It points out how caste permeates inside the predominantly Muslim society of Pakistan. Since the time Liaquat Ali Khan rejected the suggestion and demand of non-Muslim members of the legislative assembly to develop a legislative mechanism to curb social exclusion and violence around caste, the Pakistani state denies the existence of caste in Pakistan – because ideologically speaking Islam never condoned it. However, the lived experiences and marriage patterns in Pakistani society do point to the presence of certain kind of endogamy that is a central feature of any caste system. By studying the outcast groups like Churha, Dr. Ayra bring the caste question to the very centre of social theory in Pakistan.

Secondly, it also questions the popular wisdom of the neoliberal type that attributes messianic properties to the market and the process of privatisation. It provides case studies on how precarity for sweepers increased after the contract system was introduced by waste disposal departments in Lahore.

Thirdly, it also brings in the category of class to question the traditionally privileged communitarian view of seeing and studying minority groups and their politics in Pakistan. It highlights the regressive role of Christian ecclesiastical authorities in projecting the victimhood narrative to further their own class interests rather than uplifting the poor Christians in any substantive manner.

In bringing together the critique of market, class and caste, this book can provides a well-knitted theoretical framework that combines discursive (how the exclusion is framed), institutional (laws and other departments of state) and structural (gender and caste) elements. It makes the book not only informative for the public but will also remain valuable to researchers working on issues of exclusion, discrimination and human rights in Pakistan.

Dr Ayra should be congratulated on writing a well-rounded book that weaves together a complex and multi-axial narrative of discrimination, exclusion and coloniality affecting the most downtrodden group of female sweepers belonging to Churha castes. The most important feature of the book is the flow of the narrative and the speed with which themes and events unfold. It makes for a captivating read and made it hard to leave as soon one starts reading it. Some parts of the book (chapter 2) discuss academic theory but the way it has been articulated by the author even a non-academic reader can also enjoy reading it. One should congratulate not only the author but also the editors of the book who have done an incredible job of improving the readability. The title cover is very original and illustrates the exclusion in an artistic way. The book is published by Folio books could be order from their online web page. It could be ordered online from the website of the publisher.

The Book is divided into four well-written chapters dealing with the place of Christians, discursively and socio-politically, in the master narrative and realpolitik of the Pakistani state. The second chapter is the most important, insightful and moving commentary on the baggage of identities and how they overwhelm individuals, families and generations of Churha communities seen from the lens of its female members. It dives into history, spatiality and gendered reality that reinforces a burden and inhibits the political agency of christian men and women workers. The third chapter mainly documents the indignity and precarity attached to neoliberal forms of employment how it directly undermines the safety of Christian women workers and many a time led to sexual harassment and even physical violence at the workplace.

The last chapter is about the dream of social mobility shared by Christian girls and how they turn sour. It uses case studies of working women who were able to get into more ‘respectable’ professions and still could not find themselves out of the zone of exclusion. It also documents cases of those women who choose to convert for improving social acceptability but actually become victim of double oppression. They remain a Churha even after becoming Muslim, wrongly believing that egalitarian ethos of Islam will help them in achieving dignity, and in the process also squander the support mechanism of family and community. Another contribution of this chapter is to bring out to light the role of colonial laws like, 1865 Christian marriage Act, in undermining the agency of christian women from lower castes. The law only allows the legal dissolution of marriage if one partner claims and prove that her spouse has done adultery. It leads to legal battles and public mudslinging on each other’s character by creating flimsy grounds. These structural realities of poverty and untouchability put women belonging to churha castes in an unending cycle of exclusion.

The book has made some important contributions to the academic understanding of exclusion, marginality and gender studies. It points out how caste permeates inside the predominantly Muslim society of Pakistan. Since the time Liaquat Ali Khan rejected the suggestion and demand of non-Muslim members of the legislative assembly to develop a legislative mechanism to curb social exclusion and violence around caste, the Pakistani state denies the existence of caste in Pakistan – because ideologically speaking Islam never condoned it. However, the lived experiences and marriage patterns in Pakistani society do point to the presence of certain kind of endogamy that is a central feature of any caste system. By studying the outcast groups like Churha, Dr. Ayra bring the caste question to the very centre of social theory in Pakistan.

Secondly, it also questions the popular wisdom of the neoliberal type that attributes messianic properties to the market and the process of privatisation. It provides case studies on how precarity for sweepers increased after the contract system was introduced by waste disposal departments in Lahore.

Thirdly, it also brings in the category of class to question the traditionally privileged communitarian view of seeing and studying minority groups and their politics in Pakistan. It highlights the regressive role of Christian ecclesiastical authorities in projecting the victimhood narrative to further their own class interests rather than uplifting the poor Christians in any substantive manner.

In bringing together the critique of market, class and caste, this book can provides a well-knitted theoretical framework that combines discursive (how the exclusion is framed), institutional (laws and other departments of state) and structural (gender and caste) elements. It makes the book not only informative for the public but will also remain valuable to researchers working on issues of exclusion, discrimination and human rights in Pakistan.