Liver disease patient Amjad may or may not survive just like hundreds of other people for one bizarre reason: They live in Pakistan and their doctors are in India.

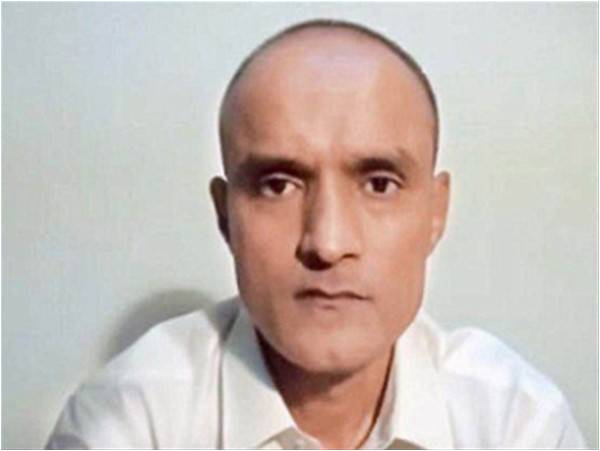

For the past two months, the Indian High Commission in Islamabad has placed an undeclared freeze on medical visas to Pakistani patients. A Foreign Office official told The Friday Times that the number of pending visas on medical grounds had reached 1,000 since January 2017. The Indian High Commission, which had already slowed down the process, has not issued any visa since April 10, the day Indian spy suspect Kulbhushan Jadhav was awarded the death sentence by a military court.

“We waited and waited outside the [Indian] embassy, but came back empty-handed,” said Amjad’s uncle Muhammad Anas. The family has already visited the Indian capital a few times for pre-operation assessments and documentation. The operation was scheduled to take place on April 28 at New Delhi’s famed Apollo Hospital.

Last year, the hospital claimed to perform liver transplants of 500 Pakistani patients every month. For Pakistani patients needing liver transplants, the choice of India is simple; it is affordable and convenient. Instead of eating into their life savings, the patients can hope to undertake the entire process for an estimated Rs2 million to Rs3 million, which is said to be half the price if they chose Europe or the United States. (A lung transplant at the Florida General Hospital, for example, costs $600,000 or Rs62 million.)

“They want us to get a letter from (Advisor on Foreign Affairs) Sartaj Aziz to their Foreign Minister (Sushma Swaraj),” his uncle said. “And that goes for all the patients these days.”

But that is easier said than done for people do not have access to the top executive of the Foreign Office. Consequently, they either have to wait until the situation normalizes or they arrange for more money to take the patient to consult in hospitals located elsewhere.

Last week, Pakistan summoned the Indian deputy high commissioner to the Foreign Office and lodged a strong protest. The diplomat was informed that human rights of the people of both countries must not suffer if relations were strained between the South Asian neighbours. In return, the diplomat submitted two petitions – one from Mr Jadhav’s mother who is also seeking a Pakistani visa to meet her son and the second from the Indian government to get immediate consular access.

The case of Mr Jadhav has, thus, seemingly turned out to be a focal point in the recent period of Pakistan-India relations. Pakistanis may say that a patient’s human rights are being violated but the Indians can argue that Jadhav could take the same position. The Indian authorities claim Mr Jadhav was kidnapped from Iran, brought to Pakistan and shown to the world as a R&AW agent working to destabilize Balochistan through a series of anti-state and sabotage activities. Pakistan has rejected these claims. Indian External Affairs Minister Swaraj declared Mr Jadhav “a son of India.” The right-wing parties called for “punitive action” against Pakistan to secure his release. The hullabaloo from the other side of the border prompted Pakistan to issue a strong statement that no compromise was possible on the issue.

The resumption of dialogue, issuance of medical visas and honouring bilateral agreements appear to be contingent to what happens to him. The India spy has two remedies available. He can file an appeal with the military authorities and a mercy petition to the President of Pakistan. However, one argument is that an execution may not make sense if Mr Jadhav is seen as evidence of Indian involvement in Pakistan. Lt-Gen (r) Raza Muhammad Khan, a former president of the National Defence University said: “I think his death sentence might be converted into life-imprisonment provided he cooperates with the authorities.”

But as far as Dr Riffat Hussain of the National University of Science and Technology is concerned, the Indian government has added another black chapter to its record of human rights violations. He said depriving Pakistani patients of urgent medical treatment was inhuman and callous. For his part, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi, Pakistan’s former ambassador to New Delhi, proposed that the issue of human rights violations by the Indian government needed to be highlighted at every important international forum.

Regardless of what transpires at the official level, the people of two countries can suffer when ties are strained. The Indian government pursues an ambitious policy of making India the top destination in Asia for medical tourism, leaving Thailand and Singapore behind. It has eased visa requirements for almost 150 countries. Pakistan is certainly not among them.

Pakistani patients and their families who visited India pre-Jadhav had found the doctors and people friendly and hospitable. More importantly, they did not face language or cultural barriers. Most of them had developed hope for a new lease on life which given the current situation, is fading day by day.

Shahzad Raza is an-Islamabad based journalist and tweets at @OldPakistan_

For the past two months, the Indian High Commission in Islamabad has placed an undeclared freeze on medical visas to Pakistani patients. A Foreign Office official told The Friday Times that the number of pending visas on medical grounds had reached 1,000 since January 2017. The Indian High Commission, which had already slowed down the process, has not issued any visa since April 10, the day Indian spy suspect Kulbhushan Jadhav was awarded the death sentence by a military court.

“We waited and waited outside the [Indian] embassy, but came back empty-handed,” said Amjad’s uncle Muhammad Anas. The family has already visited the Indian capital a few times for pre-operation assessments and documentation. The operation was scheduled to take place on April 28 at New Delhi’s famed Apollo Hospital.

Last year, the hospital claimed to perform liver transplants of 500 Pakistani patients every month. For Pakistani patients needing liver transplants, the choice of India is simple; it is affordable and convenient. Instead of eating into their life savings, the patients can hope to undertake the entire process for an estimated Rs2 million to Rs3 million, which is said to be half the price if they chose Europe or the United States. (A lung transplant at the Florida General Hospital, for example, costs $600,000 or Rs62 million.)

“They want us to get a letter from (Advisor on Foreign Affairs) Sartaj Aziz to their Foreign Minister (Sushma Swaraj),” his uncle said. “And that goes for all the patients these days.”

But that is easier said than done for people do not have access to the top executive of the Foreign Office. Consequently, they either have to wait until the situation normalizes or they arrange for more money to take the patient to consult in hospitals located elsewhere.

Last week, Pakistan summoned the Indian deputy high commissioner to the Foreign Office and lodged a strong protest. The diplomat was informed that human rights of the people of both countries must not suffer if relations were strained between the South Asian neighbours. In return, the diplomat submitted two petitions – one from Mr Jadhav’s mother who is also seeking a Pakistani visa to meet her son and the second from the Indian government to get immediate consular access.

The case of Mr Jadhav has, thus, seemingly turned out to be a focal point in the recent period of Pakistan-India relations. Pakistanis may say that a patient’s human rights are being violated but the Indians can argue that Jadhav could take the same position. The Indian authorities claim Mr Jadhav was kidnapped from Iran, brought to Pakistan and shown to the world as a R&AW agent working to destabilize Balochistan through a series of anti-state and sabotage activities. Pakistan has rejected these claims. Indian External Affairs Minister Swaraj declared Mr Jadhav “a son of India.” The right-wing parties called for “punitive action” against Pakistan to secure his release. The hullabaloo from the other side of the border prompted Pakistan to issue a strong statement that no compromise was possible on the issue.

Last year, Apollo Hospital in New Delhi claimed to perform liver transplants of 500 Pakistani patients every month. For Pakistani patients needing liver transplants, the choice of India is simple; it is affordable and convenient. Instead of eating into their life savings, the patients can hope to undertake the entire process for an estimated Rs2 million to Rs3 million

The resumption of dialogue, issuance of medical visas and honouring bilateral agreements appear to be contingent to what happens to him. The India spy has two remedies available. He can file an appeal with the military authorities and a mercy petition to the President of Pakistan. However, one argument is that an execution may not make sense if Mr Jadhav is seen as evidence of Indian involvement in Pakistan. Lt-Gen (r) Raza Muhammad Khan, a former president of the National Defence University said: “I think his death sentence might be converted into life-imprisonment provided he cooperates with the authorities.”

But as far as Dr Riffat Hussain of the National University of Science and Technology is concerned, the Indian government has added another black chapter to its record of human rights violations. He said depriving Pakistani patients of urgent medical treatment was inhuman and callous. For his part, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi, Pakistan’s former ambassador to New Delhi, proposed that the issue of human rights violations by the Indian government needed to be highlighted at every important international forum.

Regardless of what transpires at the official level, the people of two countries can suffer when ties are strained. The Indian government pursues an ambitious policy of making India the top destination in Asia for medical tourism, leaving Thailand and Singapore behind. It has eased visa requirements for almost 150 countries. Pakistan is certainly not among them.

Pakistani patients and their families who visited India pre-Jadhav had found the doctors and people friendly and hospitable. More importantly, they did not face language or cultural barriers. Most of them had developed hope for a new lease on life which given the current situation, is fading day by day.

Shahzad Raza is an-Islamabad based journalist and tweets at @OldPakistan_