Goldman Sachs (GS) issued a paper last month projecting that Pakistan’s economy will become the world’s sixth largest economy by 2075. The projection came as a big surprise, since Pakistan’s economy has been in the doldrums for decades.

The GS projection is largely based on two assumptions: the rate of population growth and the rate of productivity growth. How much confidence can we place in the projection?

One way to test its validity is by doing a “gedanken” or thought experiment. In 1960, applying the GS methodology, what would we have projected five decades out, in 2010? How does that compare with what came to pass?

Pakistan has had consistent population growth of around 3 percent a year for years. Using that as a driver, Pakistan’s economy would have ranked very high by 2010. Yet it has not fared well, as discussed in detail below.

Why is that the case? Both trade and fiscal balances are in the red. Foreign debt is high. The rupee continues to fall. Inflation is rampant. The domestic savings rate is low, as is the tax base. The country continues to spend heavily on defense, since it’s engaged in an arms race with India. All these factors which retard economic development are constant in Pakistan’s history. Interestingly, most of them were called out by Parvez Hasan when he published a review of Pakistan’s first 50 years in 1997. Hasan is a renowned Pakistani economist who served as the chief economist at the World Bank.

Pakistan also has several infrastructure issues. As seen last year, the country has no ability to cope with floods. Nor can it supply reliable electricity to its residents. It’s resorting to power rationing.

Why has the GDP not grown in proportion to population? Because there have been many disruptive events in the history that unfolded between 1960 and 2010. Consistent economic policies have not been followed. Political stability has been missing and frequent wars with India and more recently with Afghanistan have marred what could have been a smooth economic progression.

Pakistan was under military rule in 1960, with Ayub Khan at the helm. In October 1958, he seized power through a coup, saying that he was the indispensable saviour. In the early sixties, the economy began to grow rapidly. In fact, Walt Rostow said Pakistan was in the take-off stage of economic development. Experts from South Korea visited Pakistan, hoping to learn the secrets of economic planning.

Then came the Indo-China border war of 1962, and the rush of American arms to India to shore up its defenses. Ayub and his advisors worried that the chance to wrest Kashmir from India was going to slip from their hands. They plunged Pakistan into war with India in 1965. The ensuing stalemate led to a nationwide disillusionment with Ayub’s policies. To divert attention, he decided to observe a Decade of Development in 1968, which added insult to injury.

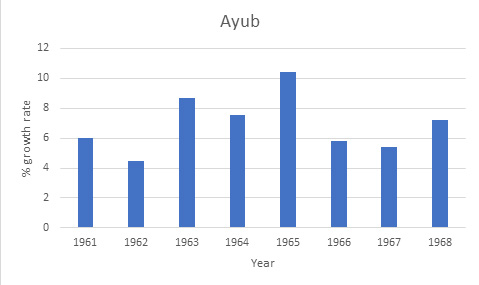

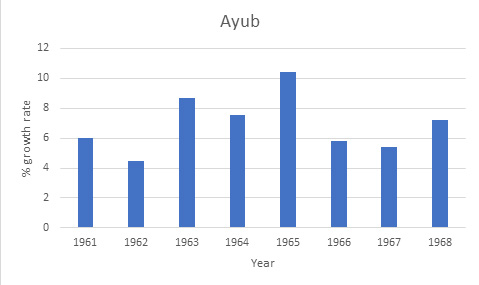

Economic growth during Ayub’s period is shown in this chart. Much of it was funded by economic assistance from the US. Ayub’s model of economic growth was the classical capitalistic model, in which concentration of wealth was emphasised. This led to the growth of the 22 families, described by one writer as the Robber Barons. Ayub’s economist, Mahbub ul Haq, famously said that the road to equalities ran through inequalities. He would reverse his position decades later, when he created the Human Development Index.

In March 1969, Ayub was deposed by the army chief General Yahya, who promised to hold fair elections to resolve the political stalemate. They were held in 1970 but Yahya, under pressure from the elite which was based in West Pakistan, annulled them the following year. In March 1971, just two years after coming to office, Yahya unleashed the fury of the Pakistani army in East Pakistan, leading to its secession.

In late December 1971, having presided over the breakup of Pakistan, one of the largest postcolonial states to break up, Yahya was deposed by the army and replaced by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, whose party had won the most seats in the 1970 elections.

Bhutto, one-time Ayub’s protégé, had turned on his boss after the 1965 war. He saw how the capitalistic model had lost favour with the public and came up with a populist alternative, Islamic Socialism. Despite its obvious contradictions, it had won him the most seats in West Pakistan.

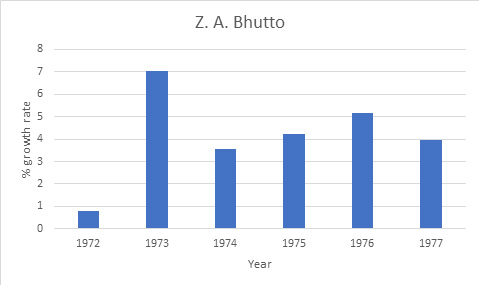

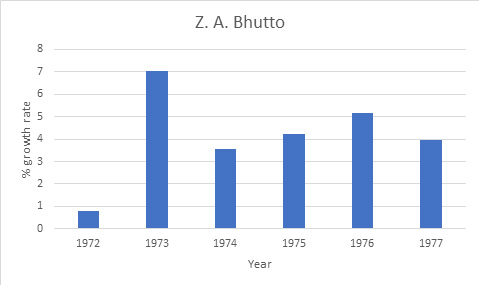

Bhutto remained one of the richest landlords in the country, despite all his talk about socialism. He did little to break up the power of the feudal lords, nor did he tax agricultural incomes. Instead, he focused on economy-wide nationalisation, which proved to be a disaster. He also focused on demeaning not only his political opponents but also squelching dissent within his own party. Despite his bold promises to provide “food, clothing and shelter to every human being,” the country and the economy suffered.

He was overthrown in a coup in 1977 by General Zia, after a large swell of public opinion accused him of having rigged the elections that gave him a second term.

The army chief, General Muhammed Ziaul Haq, said he had intervened to save the country through “Operation Fairplay” and would hold new elections in 90 days. But he kept on deferring them. In two years, Bhutto was hanged on a charge of having ordered the murder of a political rival. Zia became a global pariah but his credentials were restored when he decided to join hands with the US in opposing the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

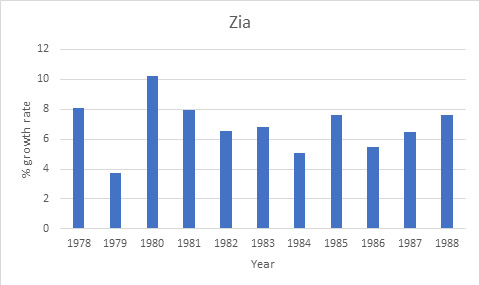

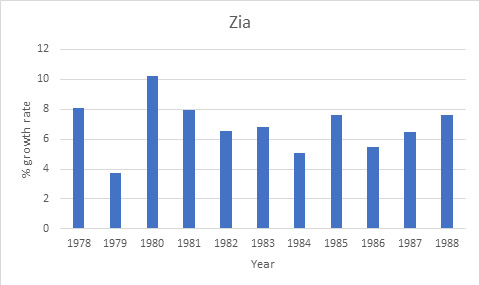

Large amounts of US aid began to flow into Pakistan. The economic indicators looked good and, in retrospect, the economy showed growth rates that were quite similar to the ones seen in Ayub’s tenure.

But the growth rates hid underlying turmoil. Zia had inserted religion into the body politic of the country, by creating the “holy warriors” in Afghanistan to fight the infidel Soviets. A new moniker was created, “Kalashnikov culture,” to describe the sad transformation that had taken place.

Zia showed no signs of leaving office, fueling resentment both inside and outside the army. He also earned the ire of the Soviets by laying out an ambitious plan to create a Muslim block including the Central Asian Republics, Iran and Pakistan. A mysterious plane crash in August 1989 ended his reign.

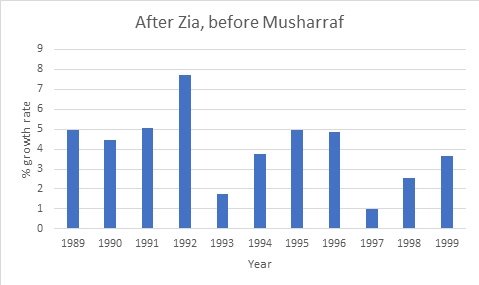

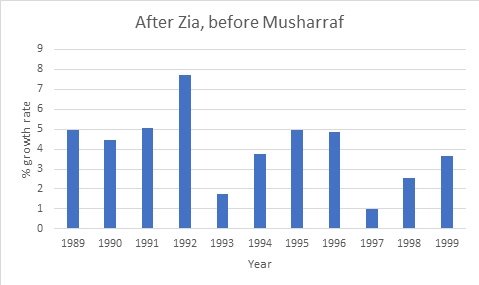

A tempestuous period of civilian rule followed, which saw the two leading parties changing roles. Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of Z. A. Bhutto, and Nawaz Sharif, who was Gen. Zia’s protégé, alternated as the two prime ministers. Economic growth was insipid and uneven. Corruption was rampant.

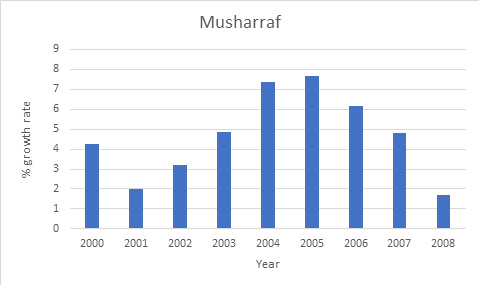

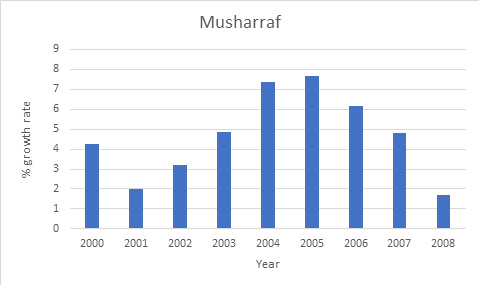

In October 1999, General Pervez Musharraf overthrew Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, claiming to save the country. He promised to bring “enlightened moderation” to the country and to restore prosperity and tranquility. His claims turned out to be hollow, both politically, since terrorism flourished, and economically, as seen in the chart below.

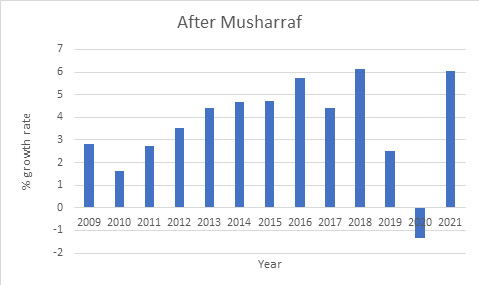

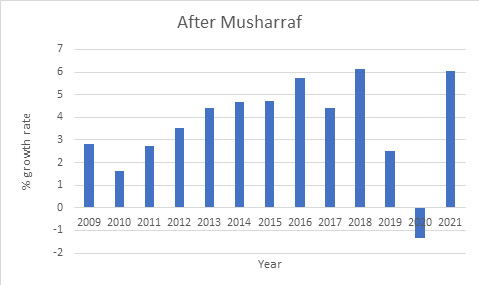

His tenure was followed by several years of civilian rule under Asif Zardari and Nawaz Sharif. However, the economy failed to regain its balance.

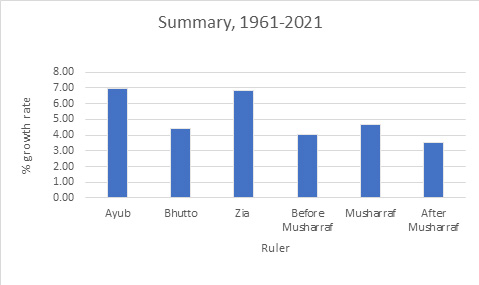

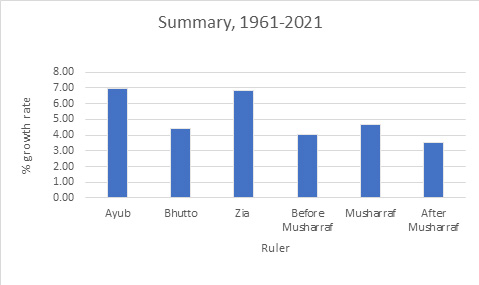

The rates of growth during the 60 years from 1961 to 2021 under the different rulers and alternating bouts of civilian and military rule are summarised below. The two decade-long periods when Ayub and Zia governed the country as military dictators stand out as the periods with the highest growth rates. But it should be borne in mind that these were the periods when Pakistan received large amounts of economic and military aid from the US. And that much damage was done to the political institutions of the country during those periods.

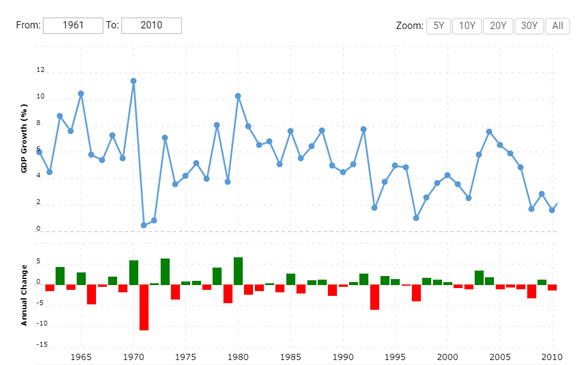

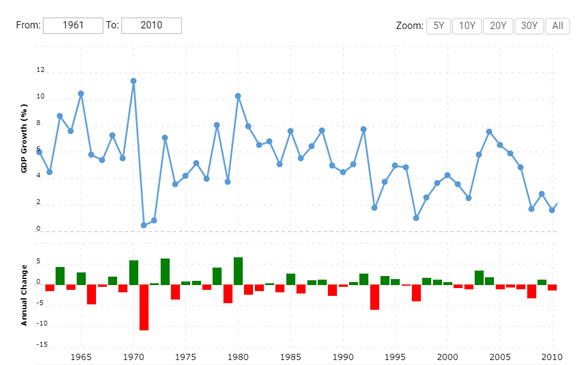

Between 1960 and 2010, the economy grew at an average rate of 5.4 percent, hardly the type of growth rate that would have moved Pakistan significantly up the ranking of world economies in that half century. Year-to-year growth was uneven, as seen in the chart below.

This result was very different from what the GS methodology would have predicted. All long term projections are guesses at best, especially those that don’t account for underlying changes in the structure of politics and economics. Over a 50-year time horizon, there are many uncertainties that can occur, economic, political, cultural and technological.

Pakistan’s future can only be projected using scenario analysis. Even then, it’s not a trivial task. The scenarios have to represent different states of the world, not just different outcomes within a given world.

That’s what I attempted to do back in July 2001, at a seminar organised by the Strategic Studies Institute of the US Army War College in Washington, DC. I laid out six scenarios for the year 2015, ranging from the very bright to the very dismal. In the “very bright” scenario, the economy grew at a rate comparable to that of the Asian Tigers. In the “bright” scenario, it grew at the rate which Pakistan had grown at in the early sixties. Alas, neither of those two scenarios materialised between 2001 and 2015. What came to pass were the darker scenarios I had sketched out.

Just two months after the seminar, 9/11 occurred. While I had recognized the presence of Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan as a disruptive event, I had presumed the worst case would be that he would take over the governance of Afghanistan from Mullah Omar and start pushing the regional boundaries. I had not envisaged a future in which he would attack the US in New York City and plunge the world into a war against terror.

After 9/11, the US invaded Afghanistan, pushing Pakistan into the “eye of the storm.” I had factored in some disruptive events in my scenario analysis but none so disruptive as 9/11. As Peter Drucker wrote, disruptive events have no probability of occurrence. But knowing in advance what they would be is no easy task. Not even the brightest of analysts foresaw the fall of the Berlin Wall, as Drucker pointed out.

Pakistan’s economic future will depend largely on two things: its political future and how it manages its economy. The two are intertwined. Population growth by itself will not promote economic development. In fact, unhindered population growth will harm its economy.

Returning to answer the question posed at the beginning of this column, the GS methodology applied to Pakistan in 1960 would have projected a very rosy outlook for Pakistan in 2010, which would have been totally off the mark.

The GS projection is largely based on two assumptions: the rate of population growth and the rate of productivity growth. How much confidence can we place in the projection?

One way to test its validity is by doing a “gedanken” or thought experiment. In 1960, applying the GS methodology, what would we have projected five decades out, in 2010? How does that compare with what came to pass?

Pakistan has had consistent population growth of around 3 percent a year for years. Using that as a driver, Pakistan’s economy would have ranked very high by 2010. Yet it has not fared well, as discussed in detail below.

Why is that the case? Both trade and fiscal balances are in the red. Foreign debt is high. The rupee continues to fall. Inflation is rampant. The domestic savings rate is low, as is the tax base. The country continues to spend heavily on defense, since it’s engaged in an arms race with India. All these factors which retard economic development are constant in Pakistan’s history. Interestingly, most of them were called out by Parvez Hasan when he published a review of Pakistan’s first 50 years in 1997. Hasan is a renowned Pakistani economist who served as the chief economist at the World Bank.

Pakistan also has several infrastructure issues. As seen last year, the country has no ability to cope with floods. Nor can it supply reliable electricity to its residents. It’s resorting to power rationing.

Why has the GDP not grown in proportion to population? Because there have been many disruptive events in the history that unfolded between 1960 and 2010. Consistent economic policies have not been followed. Political stability has been missing and frequent wars with India and more recently with Afghanistan have marred what could have been a smooth economic progression.

Pakistan was under military rule in 1960, with Ayub Khan at the helm. In October 1958, he seized power through a coup, saying that he was the indispensable saviour. In the early sixties, the economy began to grow rapidly. In fact, Walt Rostow said Pakistan was in the take-off stage of economic development. Experts from South Korea visited Pakistan, hoping to learn the secrets of economic planning.

Then came the Indo-China border war of 1962, and the rush of American arms to India to shore up its defenses. Ayub and his advisors worried that the chance to wrest Kashmir from India was going to slip from their hands. They plunged Pakistan into war with India in 1965. The ensuing stalemate led to a nationwide disillusionment with Ayub’s policies. To divert attention, he decided to observe a Decade of Development in 1968, which added insult to injury.

Economic growth during Ayub’s period is shown in this chart. Much of it was funded by economic assistance from the US. Ayub’s model of economic growth was the classical capitalistic model, in which concentration of wealth was emphasised. This led to the growth of the 22 families, described by one writer as the Robber Barons. Ayub’s economist, Mahbub ul Haq, famously said that the road to equalities ran through inequalities. He would reverse his position decades later, when he created the Human Development Index.

In March 1969, Ayub was deposed by the army chief General Yahya, who promised to hold fair elections to resolve the political stalemate. They were held in 1970 but Yahya, under pressure from the elite which was based in West Pakistan, annulled them the following year. In March 1971, just two years after coming to office, Yahya unleashed the fury of the Pakistani army in East Pakistan, leading to its secession.

In late December 1971, having presided over the breakup of Pakistan, one of the largest postcolonial states to break up, Yahya was deposed by the army and replaced by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, whose party had won the most seats in the 1970 elections.

Bhutto, one-time Ayub’s protégé, had turned on his boss after the 1965 war. He saw how the capitalistic model had lost favour with the public and came up with a populist alternative, Islamic Socialism. Despite its obvious contradictions, it had won him the most seats in West Pakistan.

Bhutto remained one of the richest landlords in the country, despite all his talk about socialism. He did little to break up the power of the feudal lords, nor did he tax agricultural incomes. Instead, he focused on economy-wide nationalisation, which proved to be a disaster. He also focused on demeaning not only his political opponents but also squelching dissent within his own party. Despite his bold promises to provide “food, clothing and shelter to every human being,” the country and the economy suffered.

He was overthrown in a coup in 1977 by General Zia, after a large swell of public opinion accused him of having rigged the elections that gave him a second term.

The army chief, General Muhammed Ziaul Haq, said he had intervened to save the country through “Operation Fairplay” and would hold new elections in 90 days. But he kept on deferring them. In two years, Bhutto was hanged on a charge of having ordered the murder of a political rival. Zia became a global pariah but his credentials were restored when he decided to join hands with the US in opposing the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Large amounts of US aid began to flow into Pakistan. The economic indicators looked good and, in retrospect, the economy showed growth rates that were quite similar to the ones seen in Ayub’s tenure.

But the growth rates hid underlying turmoil. Zia had inserted religion into the body politic of the country, by creating the “holy warriors” in Afghanistan to fight the infidel Soviets. A new moniker was created, “Kalashnikov culture,” to describe the sad transformation that had taken place.

Zia showed no signs of leaving office, fueling resentment both inside and outside the army. He also earned the ire of the Soviets by laying out an ambitious plan to create a Muslim block including the Central Asian Republics, Iran and Pakistan. A mysterious plane crash in August 1989 ended his reign.

A tempestuous period of civilian rule followed, which saw the two leading parties changing roles. Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of Z. A. Bhutto, and Nawaz Sharif, who was Gen. Zia’s protégé, alternated as the two prime ministers. Economic growth was insipid and uneven. Corruption was rampant.

In October 1999, General Pervez Musharraf overthrew Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, claiming to save the country. He promised to bring “enlightened moderation” to the country and to restore prosperity and tranquility. His claims turned out to be hollow, both politically, since terrorism flourished, and economically, as seen in the chart below.

His tenure was followed by several years of civilian rule under Asif Zardari and Nawaz Sharif. However, the economy failed to regain its balance.

The rates of growth during the 60 years from 1961 to 2021 under the different rulers and alternating bouts of civilian and military rule are summarised below. The two decade-long periods when Ayub and Zia governed the country as military dictators stand out as the periods with the highest growth rates. But it should be borne in mind that these were the periods when Pakistan received large amounts of economic and military aid from the US. And that much damage was done to the political institutions of the country during those periods.

Between 1960 and 2010, the economy grew at an average rate of 5.4 percent, hardly the type of growth rate that would have moved Pakistan significantly up the ranking of world economies in that half century. Year-to-year growth was uneven, as seen in the chart below.

This result was very different from what the GS methodology would have predicted. All long term projections are guesses at best, especially those that don’t account for underlying changes in the structure of politics and economics. Over a 50-year time horizon, there are many uncertainties that can occur, economic, political, cultural and technological.

Pakistan’s future can only be projected using scenario analysis. Even then, it’s not a trivial task. The scenarios have to represent different states of the world, not just different outcomes within a given world.

That’s what I attempted to do back in July 2001, at a seminar organised by the Strategic Studies Institute of the US Army War College in Washington, DC. I laid out six scenarios for the year 2015, ranging from the very bright to the very dismal. In the “very bright” scenario, the economy grew at a rate comparable to that of the Asian Tigers. In the “bright” scenario, it grew at the rate which Pakistan had grown at in the early sixties. Alas, neither of those two scenarios materialised between 2001 and 2015. What came to pass were the darker scenarios I had sketched out.

Just two months after the seminar, 9/11 occurred. While I had recognized the presence of Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan as a disruptive event, I had presumed the worst case would be that he would take over the governance of Afghanistan from Mullah Omar and start pushing the regional boundaries. I had not envisaged a future in which he would attack the US in New York City and plunge the world into a war against terror.

After 9/11, the US invaded Afghanistan, pushing Pakistan into the “eye of the storm.” I had factored in some disruptive events in my scenario analysis but none so disruptive as 9/11. As Peter Drucker wrote, disruptive events have no probability of occurrence. But knowing in advance what they would be is no easy task. Not even the brightest of analysts foresaw the fall of the Berlin Wall, as Drucker pointed out.

Pakistan’s economic future will depend largely on two things: its political future and how it manages its economy. The two are intertwined. Population growth by itself will not promote economic development. In fact, unhindered population growth will harm its economy.

Returning to answer the question posed at the beginning of this column, the GS methodology applied to Pakistan in 1960 would have projected a very rosy outlook for Pakistan in 2010, which would have been totally off the mark.