The elections of February 8 proved that despite the trappings of democracy, Pakistan remains a Praetorian State. It was instituted when General Ayub Khan seized the reins of power on October 27, 1958. He argued that elected politicians had failed to realise Jinnah’s vision, since they were “vermin and leeches.”

In the 66 years that have elapsed since then, the country has experienced three coups, fought several wars with India, witnessed the secession of East Pakistan, and experienced uneven economic growth. Today, the Rupee is worth less than 2% of what it was worth in 1971.

More than 76 years after its birth, Pakistan is riddled with corruption, poverty, illiteracy and disease. The body politic is rife with religious differences. The strategic culture is toxic. Can it be changed?

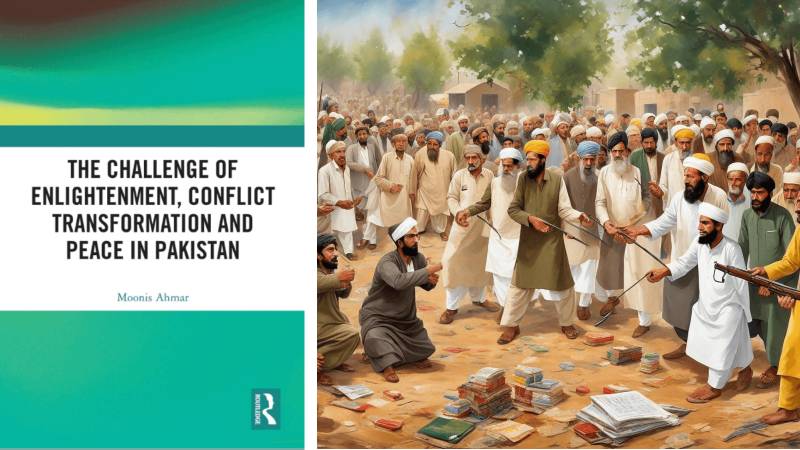

In “The Challenge of Enlightenment, Conflict Transformation and Peace in Pakistan,” Moonis Ahmar says yes. The ultra-conservative segment of society stands in the way. It “is utterly opposed to enlightenment as it will empower people to make a distinction between reason and ignorance.” Culture will not change unless the thought process changes “from conservative and dogmatic to liberal, moderate and enlightened.”

He traces many of the problems to the clergy who “resist reason and rationality,” and do not engage in “scientific and rational thought process.” They have created a “deep-rooted culture of ignorance … [which] has impeded the process of cultural enlightenment in Pakistan.”

The book concludes with yet another Utopian statement: “If Pakistan wants to be a role model of social and human development, it needs to transform its culture from knowledge-unfriendly to friendly so that people with talent, reason, creativity and innovation can come forward and transform the country as modern, scientifically developed and culturally enlightened.”

He says Europe achieved enlightenment by engaging in “reasoning, the pursuit of knowledge, science, logic, doubt and individualism.” This paved the way for Europe to “excel in the pursuit of knowledge, discovery, innovation, industrialisation and modernisation.” He acknowledges that it took Europe several centuries to get there. It worked because “Philosophers, scientists, artists and writers” played a vital role.

Ahmar argues that Pakistan can learn lessons from how Europe replaced its “medieval culture to the age of renaissance, enlightenment, geographical discoveries, industrial revolution, individualism and focusing on science, education and research.”

Ahmar teaches international relations at the University of Karachi and says, unsurprisingly, that Pakistan should promote “the culture of reading and critical thinking.” So, why has it not done so? Why will it do so in the future? These questions do not concern him.

He identifies the clergy as the primary roadblock to cultural transformation and says they can be reformed by unleashing “a process of reasoning, questioning and doubt on issues which have not been resolved so far like: the status of women in Islam; whether democracy is compatible with Islam or not, whether science and Islam are not harmonious.” But who will reform those who will condemn the reformers as heretics?

Then comes the answer. The youth will “act as a catalyst in unleashing the process of enlightenment because at stake is its future.” But will they? Today’s adults are yesterday’s youth.

He is correct when he says that if “Pakistan remains under the shadow of backward and retrogressive culture,” the youth will suffer. Indeed, the country has “to safeguard their future from intolerance, extremism, militancy, radicalisation and violence.” But why has the country not done so for the past several decades? Because those who are vested in the status quo do not want anyone, least of all their children, to end their dominance.

The book concludes with yet another Utopian statement: “If Pakistan wants to be a role model of social and human development, it needs to transform its culture from knowledge-unfriendly to friendly so that people with talent, reason, creativity and innovation can come forward and transform the country as modern, scientifically developed and culturally enlightened.”

The book makes a valiant effort to solve a very difficult problem. However, much deeper problems plague Pakistan than conservative clerics, rural population, and illiteracy.

MA Jinnah was a secular individual who never imagined that religion would become the dominant ideology of Pakistan. He thought he was creating a secular democracy, not realising that by creating a state based on the religion of its inhabitants, he was opening a door for the clergy to enter

There is little that is common between Europe and Pakistan, or between Christianity and Islam. There is also little in common with the Indus Valley and Gandhara civilisations, which existed in the same land mass as today’s Pakistan. Those civilisations predate by several millennia the arrival of Muslims in India, whose legacy is today’s Pakistan.

Many of Pakistan’s problems can be traced to the two-nation theory, which formed the basis for the creation of Pakistan. It was premised on the notion that the Muslims of the subcontinent constituted a nation and should be given their own state. But if religion could serve as the foundation for a nation-state, then the nearly 2 billion Muslims of the world would constitute a nation-state.

Indeed, Muslims are a nation in the spiritual sense of the word, which is captured in the Arabic word, “ummah.” But ummah does not mean a nation-state in the political sense of the word. If it did, there would be a single Muslim country in the world, not 49.

MA Jinnah was a secular individual who never imagined that religion would become the dominant ideology of Pakistan. He thought he was creating a secular democracy, not realising that by creating a state based on the religion of its inhabitants, he was opening a door for the clergy to enter.

The first manifestation of their power was the Ahmadiyya riots of 1953, just five years after Jinnah’s death and two years after the assassination of his deputy, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan. That triggered Pakistan’s first bout of martial law.

Nor did Jinnah realise that by going to war with India just a few months after independence, he was opening a door through which the army would enter. In just 11 years, the army would seize the commanding heights of the country. It would use that dominant role to mould Pakistan’s strategic culture and cast itself as the guardian of the country’s existence.

Instead of drawing lessons from Europe’s cultural enlightenment, the book should have reviewed the strategic culture of moderate Muslim countries such as Malaysia and Turkiye. Even with all these limitations, the book will be of interest to serious students of Pakistan.