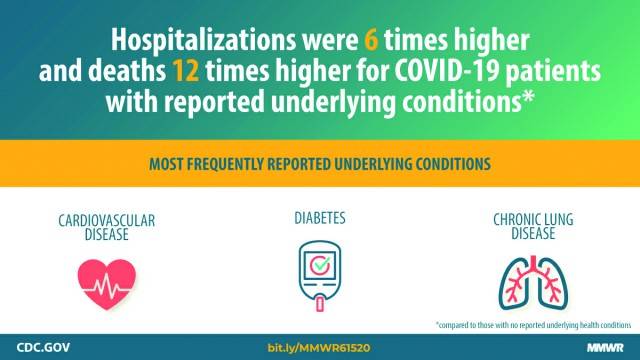

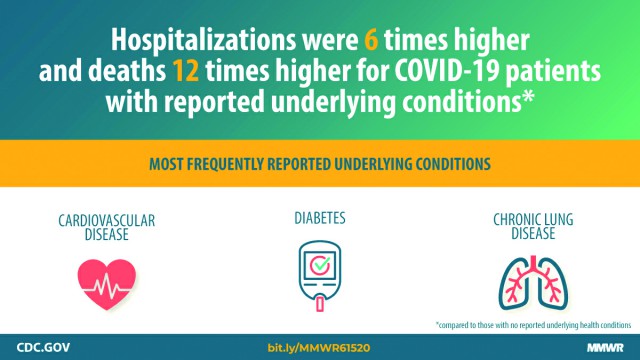

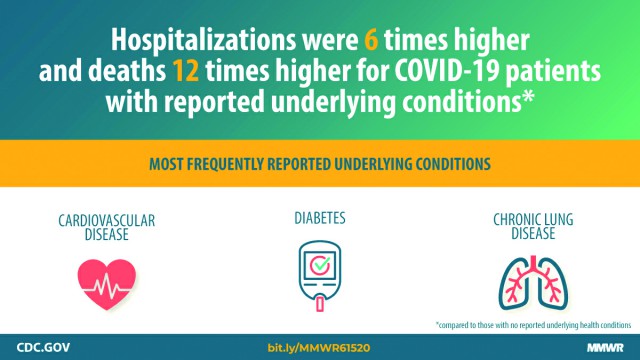

You would have to be living in a nuclear bunker or in a coma to not know that for almost a year, the world has been gripped by a devastating pandemic. If you’re like me, I find myself checking the data coming through on daily numbers of cases and deaths from COVID-19 with a morbid fascination. As a hospital doctor, I also know first hand the impact this awful disease is having on people. It is not all doom and gloom of course; it is well established that in younger and healthier people, the disease can be mild and rarely results in hospitalisation. However amongst the elderly and people with underlying health conditions, the risk of severe illness and death is much higher.

To put this into context, a recent study estimated that one quarter of the UK population had a record of at least one underlying health condition and around 7% had multiple health conditions. In other words, 18.5 million people would be considered at moderate risk of COVID-19 and almost 5 million at high risk due to the presence of multiple health conditions. To me that’s mind blowing!

So what is an underlying health condition? The same study mentions lung conditions such as asthma, chronic airways disease, heart disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (often linked with diabetes), liver disease, chronic neurological diseases, being very obese (a body mass index of greater than 40) and having treatment with medicines that suppress the immune system such as anti-cancer medicines. Pregnancy is also listed because the immune system is suppressed during pregnancy naturally. The striking thing for me is that many of these conditions are considered to be “lifestyle” related diseases. By lifestyle, I mean smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and physical activity.

To help reduce the impact of the pandemic, in the UK, we have been told repeatedly “hands, face, space” which refers to good hand hygiene, use of face coverings and social distancing. This is undoubtedly good advice although mask use outside of healthcare settings is more controversial though I doubt that extensive mask use will be harmful. What has been lacking in all the public health advice, is discussion regarding other measures that can be put into place to improve people’s health and reduce the incidence of underlying health conditions. By that I mean efforts to reduce and stop smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, increasing physical activity and perhaps most importantly of all, improving our diet. Importantly, this won’t just impact on COVID-19 . We mustn’t forget that 18 million people die from heart disease and 10 million from cancer globally dwarfing the number of deaths from COVID-19 annually.

Arguably, the defining theme of 2020 was lockdown. Consequently, many have experienced reduced physical activity, working from home and spending inordinate amounts of time in front of a computer or tablet screen. This has resulted in inevitable weight gain, comfort eating and a general lack of focus on healthy eating. I have spent a lot of time thinking about what I can do to reduce my future risk of any number of conditions and there are two lifestyle changes that really come to mind: physical activity and diet. The latter is what I would like to focus on for the remainder of the article.

We all know that we can improve our diets by eating more fresh fruit and vegetables, avoiding saturated fats and reducing the consumption of refined sugars. The traditional Western diet also has one food type that is consumed in excess and that is meat. Globally meat consumption has been increasing exponentially and this not only has an impact on individual’s health but because of modern intensive farming methods there are growing concerns about their impact on the environment.

In many Muslim countries, including Pakistan, meat is considered an essential component of any meal. It’s a sign of affluence and many delicious dishes have meat at the centre stage. Ironically, my own wedding involved excessive consumption of oily, heavy meat-based dishes. By the end of the festivities, I also remember feeling quite ill in a way that is difficult to explain. I distinctly recall the joy I felt when my aunt made “daal chawal” one lunchtime in the midst of this with a side salad and a cooling raita. I know that this was not a normal week by any standards but it demonstrated the incompatibility of such food with daily life. Closer to home, there are countless examples of gatherings where one is served several different meat dishes with not a vegetable in sight. The generosity of the well-intentioned hosts is never in question; it would require a seismic shift in mindset to change this.

Vegetarianism and veganism are rapidly being adopted by people across the globe, particularly in the global North. Of course, I am not talking about people who don’t have a choice as buying meat may not be a financial option. People are becoming aware of the health and environmental benefits of a plant-based diet. I think that these changes will take much longer to establish in a country like Pakistan. Part of the reason for this is cultural. There may also be reluctance to follow a plant-based diet as this would rightly or wrongly be associated with dietary habits of the majority of the inhabitants of Pakistan’s neighbour and long-time rival.

Plant-based eating focuses on foods primarily from plants. Beyond fruits and vegetables this also includes nuts, seeds, oils, whole grains, legumes, and beans. You don’t have to be a vegetarian or vegan and never eat meat or dairy. Rather, you are proportionately choosing more of your foods from plant sources.

I am not a nutritionist and so I won’t pretend to know everything there is about the evidence that plant-based eating patterns are healthy. However, one such diet is the Mediterranean diet and there is now abundant evidence that it can reduce risk of heart disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, certain cancers (specifically prostate, colon and breast cancer) and depression. Amongst older individuals, there is a decrease in frailty and better mental and physical function. Vegetarian diets are also linked with lower risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes and a longer life. The Mediterranean diet has a foundation of plant-based foods; it also includes fish, poultry, eggs, cheese and yoghurt a few times a week, with meats and sweets less often.

Many people counter the vegetarian and vegan argument by stating that they are deficient in protein and essential vitamins. However, plant-based diets offer all the necessary protein, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals for optimal health, and are often higher in fibre and phytonutrients. Vegans may need to add vitamin B12 to their diet but this will depend on individual circumstances.

I am not personally advocating a vegetarian or vegan diet. This should always be a personal choice. I love certain meats and dairy products and I would miss them too much if I completely cut them out of my diet. We are always being bombarded by the latest fad or diet craze and if you get sucked into that particular vortex, life can get too complicated. All I suggest is that people should make the following simple changes to their diet at a pace that they can manage:

Breakfast: increase use of whole grains such as oats, quinoa, buckwheat and barley. Try adding nuts and seeds as well as fresh fruit.

Change your relationship with meat. Eat fewer and smaller portions and treat it as an accompaniment rather than a centerpiece.

Start off with one meal a week where you don’t eat meat. Don’t just have potatoes or bread, enjoy beans, vegetables and whole grains. Gradually increase it to more and more meals each week.

Focus on vegetables, try to make sure that at least half your plate is composed of vegetables with every meal and try the rainbow approach where you choose as many colours as possible for your plate.

Green your plate: focus on leafy vegetables such as spinach, kale, cabbage, watercress, romaine lettuce, Swiss chard, pak choi, turnip greens and beet greens. The latter two are often discarded as a waste product of these root vegetables but are more nutritious than their bottom half! Don’t just boil them, try steaming, grilling, braising or stir-frying to maximise their nutritive value.

Salads: try making these a centrepiece for as many meals as possible. Jazz them up with tofu, small quantities of cheese, nuts, seeds, beans, peas and fresh herbs. Some fruits like apple and pomegranate work beautifully in salads as do sundried tomatoes.

Healthy oils and fats: olives, olive oil, coconut oil, nuts and nut butters, seeds and avocados are excellent sources of so called good fats and should replace butter, ghee and refined vegetable and corn oils.

Dairy: limit this or even replace with alternatives such as oat milk, rice milk and nut milks. Remember lactose intolerance is much more common than people appreciate and the hormones and antibiotics used in modern dairy farming don’t bring any health benefits.

Sweets: switch refined sugar based desserts with fresh fruit. Even the sweetest fruit won’t have as much sugar as a pudding, cake or large piece of chocolate. Dried fruits are also a great alternative and I often find myself reaching for a date or a fig when I need a sweet fix with a cup of tea.

Processed fast foods: these are undeniably popular and convenient, and in the West, very cheap but there’s very little if any nutritional value in most fast foods and consumption should be limited to the bare minimum.

I am not suggesting that all my recommendations should be followed to the letter. I am not preaching a dogmatic lifestyle. I strongly believe that the only change worth making is one that can be sustained and small changes made steadily over time are much easier to adopt than a dramatic change in gear.

I am also not deluded into thinking that all ill health is preventable by diet alone. Genetics play a part and normal human aging is associated with disease and errors that give rise to conditions like cancer. However, the diseases of overconsumption are increasing and these and the obesity pandemic in the Western world will continue to have an impact on people’s lives and the ability for health care systems to cope with the demands placed on them. We should at the very least try to control what we can and if you are blessed with the ability and financial means to eat what you want, then choosing a plant-based diet may make all the difference.

Dr Omar Khan is a consultant oncologist in the UK. He has a PhD in Clinical Pharmacology from the University of Oxford

To put this into context, a recent study estimated that one quarter of the UK population had a record of at least one underlying health condition and around 7% had multiple health conditions. In other words, 18.5 million people would be considered at moderate risk of COVID-19 and almost 5 million at high risk due to the presence of multiple health conditions. To me that’s mind blowing!

So what is an underlying health condition? The same study mentions lung conditions such as asthma, chronic airways disease, heart disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (often linked with diabetes), liver disease, chronic neurological diseases, being very obese (a body mass index of greater than 40) and having treatment with medicines that suppress the immune system such as anti-cancer medicines. Pregnancy is also listed because the immune system is suppressed during pregnancy naturally. The striking thing for me is that many of these conditions are considered to be “lifestyle” related diseases. By lifestyle, I mean smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and physical activity.

To help reduce the impact of the pandemic, in the UK, we have been told repeatedly “hands, face, space” which refers to good hand hygiene, use of face coverings and social distancing. This is undoubtedly good advice although mask use outside of healthcare settings is more controversial though I doubt that extensive mask use will be harmful. What has been lacking in all the public health advice, is discussion regarding other measures that can be put into place to improve people’s health and reduce the incidence of underlying health conditions. By that I mean efforts to reduce and stop smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, increasing physical activity and perhaps most importantly of all, improving our diet. Importantly, this won’t just impact on COVID-19 . We mustn’t forget that 18 million people die from heart disease and 10 million from cancer globally dwarfing the number of deaths from COVID-19 annually.

Arguably, the defining theme of 2020 was lockdown. Consequently, many have experienced reduced physical activity, working from home and spending inordinate amounts of time in front of a computer or tablet screen. This has resulted in inevitable weight gain, comfort eating and a general lack of focus on healthy eating. I have spent a lot of time thinking about what I can do to reduce my future risk of any number of conditions and there are two lifestyle changes that really come to mind: physical activity and diet. The latter is what I would like to focus on for the remainder of the article.

We all know that we can improve our diets by eating more fresh fruit and vegetables, avoiding saturated fats and reducing the consumption of refined sugars. The traditional Western diet also has one food type that is consumed in excess and that is meat. Globally meat consumption has been increasing exponentially and this not only has an impact on individual’s health but because of modern intensive farming methods there are growing concerns about their impact on the environment.

In many Muslim countries, including Pakistan, meat is considered an essential component of any meal. It’s a sign of affluence and many delicious dishes have meat at the centre stage. Ironically, my own wedding involved excessive consumption of oily, heavy meat-based dishes. By the end of the festivities, I also remember feeling quite ill in a way that is difficult to explain. I distinctly recall the joy I felt when my aunt made “daal chawal” one lunchtime in the midst of this with a side salad and a cooling raita. I know that this was not a normal week by any standards but it demonstrated the incompatibility of such food with daily life. Closer to home, there are countless examples of gatherings where one is served several different meat dishes with not a vegetable in sight. The generosity of the well-intentioned hosts is never in question; it would require a seismic shift in mindset to change this.

Vegetarianism and veganism are rapidly being adopted by people across the globe, particularly in the global North. Of course, I am not talking about people who don’t have a choice as buying meat may not be a financial option. People are becoming aware of the health and environmental benefits of a plant-based diet. I think that these changes will take much longer to establish in a country like Pakistan. Part of the reason for this is cultural. There may also be reluctance to follow a plant-based diet as this would rightly or wrongly be associated with dietary habits of the majority of the inhabitants of Pakistan’s neighbour and long-time rival.

Plant-based eating focuses on foods primarily from plants. Beyond fruits and vegetables this also includes nuts, seeds, oils, whole grains, legumes, and beans. You don’t have to be a vegetarian or vegan and never eat meat or dairy. Rather, you are proportionately choosing more of your foods from plant sources.

I am not a nutritionist and so I won’t pretend to know everything there is about the evidence that plant-based eating patterns are healthy. However, one such diet is the Mediterranean diet and there is now abundant evidence that it can reduce risk of heart disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, certain cancers (specifically prostate, colon and breast cancer) and depression. Amongst older individuals, there is a decrease in frailty and better mental and physical function. Vegetarian diets are also linked with lower risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes and a longer life. The Mediterranean diet has a foundation of plant-based foods; it also includes fish, poultry, eggs, cheese and yoghurt a few times a week, with meats and sweets less often.

Many people counter the vegetarian and vegan argument by stating that they are deficient in protein and essential vitamins. However, plant-based diets offer all the necessary protein, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals for optimal health, and are often higher in fibre and phytonutrients. Vegans may need to add vitamin B12 to their diet but this will depend on individual circumstances.

I am not personally advocating a vegetarian or vegan diet. This should always be a personal choice. I love certain meats and dairy products and I would miss them too much if I completely cut them out of my diet. We are always being bombarded by the latest fad or diet craze and if you get sucked into that particular vortex, life can get too complicated. All I suggest is that people should make the following simple changes to their diet at a pace that they can manage:

Breakfast: increase use of whole grains such as oats, quinoa, buckwheat and barley. Try adding nuts and seeds as well as fresh fruit.

Change your relationship with meat. Eat fewer and smaller portions and treat it as an accompaniment rather than a centerpiece.

Start off with one meal a week where you don’t eat meat. Don’t just have potatoes or bread, enjoy beans, vegetables and whole grains. Gradually increase it to more and more meals each week.

Focus on vegetables, try to make sure that at least half your plate is composed of vegetables with every meal and try the rainbow approach where you choose as many colours as possible for your plate.

Green your plate: focus on leafy vegetables such as spinach, kale, cabbage, watercress, romaine lettuce, Swiss chard, pak choi, turnip greens and beet greens. The latter two are often discarded as a waste product of these root vegetables but are more nutritious than their bottom half! Don’t just boil them, try steaming, grilling, braising or stir-frying to maximise their nutritive value.

Salads: try making these a centrepiece for as many meals as possible. Jazz them up with tofu, small quantities of cheese, nuts, seeds, beans, peas and fresh herbs. Some fruits like apple and pomegranate work beautifully in salads as do sundried tomatoes.

Healthy oils and fats: olives, olive oil, coconut oil, nuts and nut butters, seeds and avocados are excellent sources of so called good fats and should replace butter, ghee and refined vegetable and corn oils.

Dairy: limit this or even replace with alternatives such as oat milk, rice milk and nut milks. Remember lactose intolerance is much more common than people appreciate and the hormones and antibiotics used in modern dairy farming don’t bring any health benefits.

Sweets: switch refined sugar based desserts with fresh fruit. Even the sweetest fruit won’t have as much sugar as a pudding, cake or large piece of chocolate. Dried fruits are also a great alternative and I often find myself reaching for a date or a fig when I need a sweet fix with a cup of tea.

Processed fast foods: these are undeniably popular and convenient, and in the West, very cheap but there’s very little if any nutritional value in most fast foods and consumption should be limited to the bare minimum.

I am not suggesting that all my recommendations should be followed to the letter. I am not preaching a dogmatic lifestyle. I strongly believe that the only change worth making is one that can be sustained and small changes made steadily over time are much easier to adopt than a dramatic change in gear.

I am also not deluded into thinking that all ill health is preventable by diet alone. Genetics play a part and normal human aging is associated with disease and errors that give rise to conditions like cancer. However, the diseases of overconsumption are increasing and these and the obesity pandemic in the Western world will continue to have an impact on people’s lives and the ability for health care systems to cope with the demands placed on them. We should at the very least try to control what we can and if you are blessed with the ability and financial means to eat what you want, then choosing a plant-based diet may make all the difference.

Dr Omar Khan is a consultant oncologist in the UK. He has a PhD in Clinical Pharmacology from the University of Oxford