In what has become an annual event, the Aurat March (Women’s March) took place this month. The event happened in Lahore, Islamabad, Karachi, Peshawar and Hyderabad among other cities - and while exact numbers are difficult to get, I expected the march (like all public events not arranged by the religious right) to be somewhat timid. But pictures show the marches were reasonably well attended. Indeed, pictures are how I suspect most Pakistanis experienced the march at all.

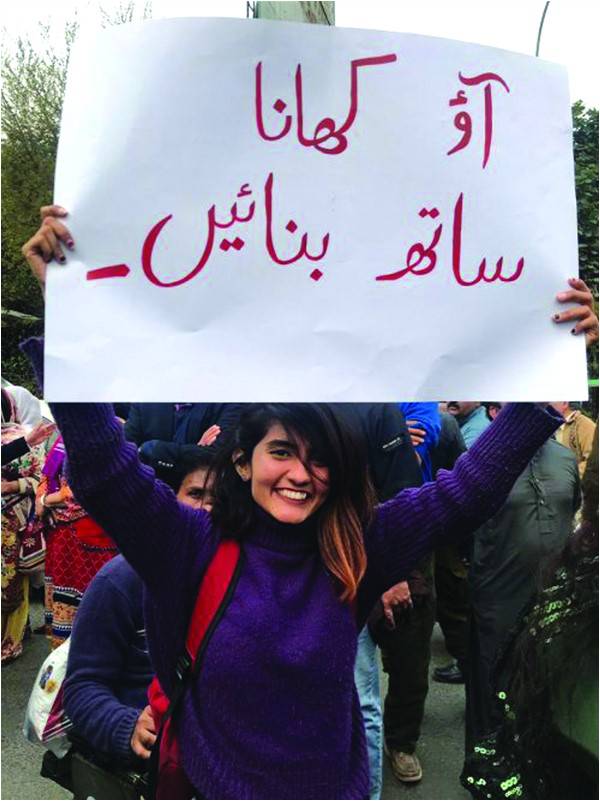

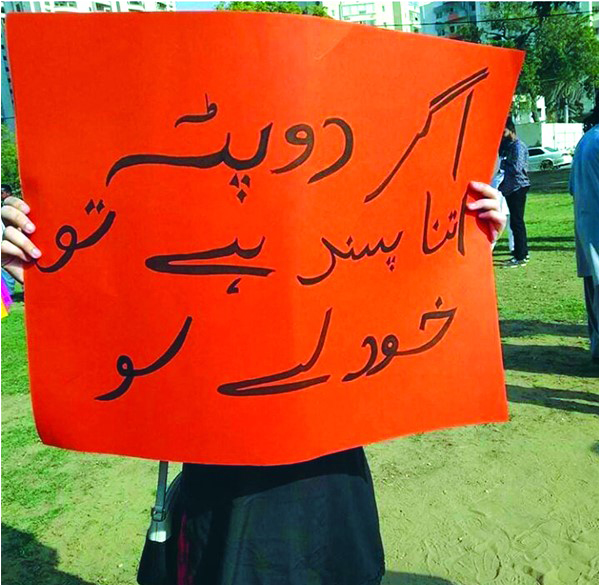

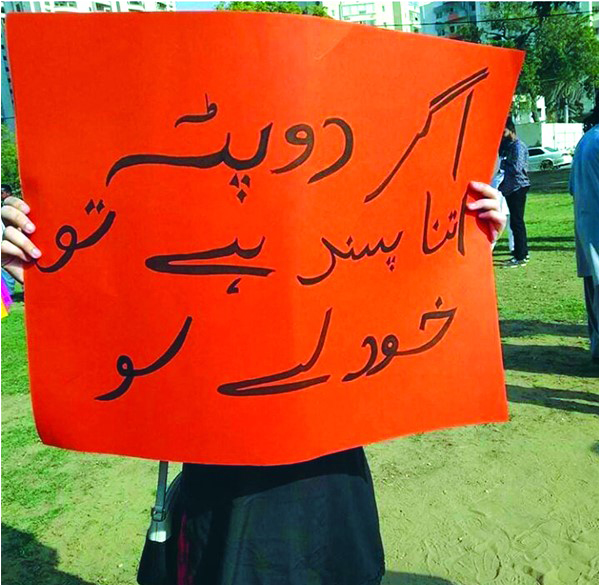

There were pictures of women locked arm-in-arm, walking defiantly down main thoroughfares; pictures of children smiling next to their mothers holding up peace signs; pictures of performers; pictures of women giving speeches, and even pictures of a group of women carrying the funeral shroud of “patriarchy”. But the pictures that got the most traction - both in print and the depths of the murky cesspool that is Pakistani Twitter - was the documentation of the different kind of placards people were carrying.

Like most protest signs, the ones here ranged from dull to defiant. Run-of-the-mill (but important) messages like “Ghar ka kaam, sab ka kaam” (Housework is everyone’s work) and the now famous “Khana khud garam karo” (Heat up your own food) jostled alongside “Nazar Teri Gandi Aur Parda Main Karoon?” (Your gaze is indecent, but I must veil myself?) and my personal favorite “My periods are not a luxury: stop taxing our pads”. And in a space where sometimes survival is an act of bravery, these signs were brave. While reading them, I found myself thinking about the women who were there. Who were they? Did they work? Were they scared? Did they come alone or in a group? Did they have to ask permission from someone to be there? Would they have to apologize to someone afterwards? Why?

For these women to have inhabited public space in Pakistan as the march encourages them to do (loudly, visibly, unapologetically) is an act of courage and defiance. Most people (in this country particularly, but mostly everywhere, really) prefer that the oppressed not call attention to their oppression. It makes people uncomfortable. And when the oppressed are 50% of the human race, it becomes a slightly more complicated dynamic. Women’s marches have become a global tool to remind us that women’s rights are not a calcified paragraph from Western history books, but a living, urgent, political, intersectional and existential fight.

I grasp on an intellectual level that a certain number of uncles and even aunties would look at the March and tut in middle-class outrage. The talk about pads and periods may make them uncomfortable. Maybe they don’t think girls should wear jeans in public. Or call attention to themselves at all.

But even I was taken aback by the vitriol that coverage of the event garnered. One of the first and most obvious criticisms was how culturally elitist and classist the event was. Calling the event Aurat March as opposed to Women’s March was a brilliant move to preemptively confront that critique and while its true that many of the women at the event may have came from privileged backgrounds compared to the rest of our population, if you go through early suffragette protest pictures you’ll see the same thing. Privilege is power; power is choice. The way women got the vote, the way slavery was abolished, the way LGBT rights fought its way out of the closet - these were all possible because people who had power used it. These fights were not all appropriate, they were not demure, or polite, or concerned with making people feel comfortable. They are messy and painful, because to make change in society is often a messy, painful thing. I found myself thinking about how many other women couldn’t be there. Were they were either taking care of a family or else simply denied permission to go? Could more people be mobilized next year and the next? Perhaps bused in from schools and villages close to the city centers? Would that be possible? As far as I’ve read, Aurat March had no corporate sponsorship. Especially as it stands in stark contrast to our Biennales, music concerts and literally festivals. That fact is as good as any at illustrating the perverse way money can prioritize (and co-opt) the narrative of social change.

One picture specifically came up on my timelines again and again. In it, three women stood smiling holding a card that said “Divorced and Happy”. It’s not a revolutionary statement by any means, but the comments were blowing up. Viewers accused the picture of glorifying divorce, encouraging a culture of amoral frivolity and generally being inappropriate. The picture gave no indication as to the subjects’ own marriages, or what they went through. But the outcry against them asserted the toxic idea that feminism - which is just another term for equality - is a Western concept that threatens to destroy familial units in South Asia. Ironically, most of the posters had pictures of twice divorced Imran Khan on their profile pictures, implying a moral compass can be as selective as it is declarative. That we can actually have a debate about whether or not women deserve to be “happy” after a divorce (apparently the worst thing is to say that they are) is infantile. We haven’t even gotten to the really polarizing subjects like abortion, marital rape, harassment, workplace sexism or any of the other fights that are fought on the battleground of women’s bodies.

I’m old enough to know that there will always be people who defend the wrong thing. They are often nice people: grandparents, fathers, mothers, sisters. They do not see themselves as misogynistic, or bigoted, or homophobic, or racist - because people tend not to see that side of themselves unless forced to. Which is why representation matters.

Seeing people standing for what they believe in, matters.

It matters to me that thousands of people came to Mumtaz Qadri’s funeral and were proud to be seen there because it illustrated how very deeply rooted the problems in our cultural equilibrium really were. It matters that at Asma Jahangir’s funeral women stood along side men at the prayer, because the next time that happens, maybe it’ll matter less. It matters that women actually see other women marching in public, and yes, talking about their periods and pads and divorces if that’s what they feel they want to do. It matters because then we are all forced to confront in practice what so many people claim to support only in theory. It matters.

But you know what doesn’t matter? What men have to say about it. I realize that may come across as slightly weird considering I’ve spent the last five minutes telling you what I think, but you know what I mean.

March on.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

There were pictures of women locked arm-in-arm, walking defiantly down main thoroughfares; pictures of children smiling next to their mothers holding up peace signs; pictures of performers; pictures of women giving speeches, and even pictures of a group of women carrying the funeral shroud of “patriarchy”. But the pictures that got the most traction - both in print and the depths of the murky cesspool that is Pakistani Twitter - was the documentation of the different kind of placards people were carrying.

Like most protest signs, the ones here ranged from dull to defiant. Run-of-the-mill (but important) messages like “Ghar ka kaam, sab ka kaam” (Housework is everyone’s work) and the now famous “Khana khud garam karo” (Heat up your own food) jostled alongside “Nazar Teri Gandi Aur Parda Main Karoon?” (Your gaze is indecent, but I must veil myself?) and my personal favorite “My periods are not a luxury: stop taxing our pads”. And in a space where sometimes survival is an act of bravery, these signs were brave. While reading them, I found myself thinking about the women who were there. Who were they? Did they work? Were they scared? Did they come alone or in a group? Did they have to ask permission from someone to be there? Would they have to apologize to someone afterwards? Why?

For these women to have inhabited public space in Pakistan as the march encourages them to do (loudly, visibly, unapologetically) is an act of courage and defiance. Most people (in this country particularly, but mostly everywhere, really) prefer that the oppressed not call attention to their oppression. It makes people uncomfortable. And when the oppressed are 50% of the human race, it becomes a slightly more complicated dynamic. Women’s marches have become a global tool to remind us that women’s rights are not a calcified paragraph from Western history books, but a living, urgent, political, intersectional and existential fight.

I grasp on an intellectual level that a certain number of uncles and even aunties would look at the March and tut in middle-class outrage. The talk about pads and periods may make them uncomfortable. Maybe they don’t think girls should wear jeans in public. Or call attention to themselves at all.

But even I was taken aback by the vitriol that coverage of the event garnered. One of the first and most obvious criticisms was how culturally elitist and classist the event was. Calling the event Aurat March as opposed to Women’s March was a brilliant move to preemptively confront that critique and while its true that many of the women at the event may have came from privileged backgrounds compared to the rest of our population, if you go through early suffragette protest pictures you’ll see the same thing. Privilege is power; power is choice. The way women got the vote, the way slavery was abolished, the way LGBT rights fought its way out of the closet - these were all possible because people who had power used it. These fights were not all appropriate, they were not demure, or polite, or concerned with making people feel comfortable. They are messy and painful, because to make change in society is often a messy, painful thing. I found myself thinking about how many other women couldn’t be there. Were they were either taking care of a family or else simply denied permission to go? Could more people be mobilized next year and the next? Perhaps bused in from schools and villages close to the city centers? Would that be possible? As far as I’ve read, Aurat March had no corporate sponsorship. Especially as it stands in stark contrast to our Biennales, music concerts and literally festivals. That fact is as good as any at illustrating the perverse way money can prioritize (and co-opt) the narrative of social change.

One picture specifically came up on my timelines again and again. In it, three women stood smiling holding a card that said “Divorced and Happy”. It’s not a revolutionary statement by any means, but the comments were blowing up. Viewers accused the picture of glorifying divorce, encouraging a culture of amoral frivolity and generally being inappropriate. The picture gave no indication as to the subjects’ own marriages, or what they went through. But the outcry against them asserted the toxic idea that feminism - which is just another term for equality - is a Western concept that threatens to destroy familial units in South Asia. Ironically, most of the posters had pictures of twice divorced Imran Khan on their profile pictures, implying a moral compass can be as selective as it is declarative. That we can actually have a debate about whether or not women deserve to be “happy” after a divorce (apparently the worst thing is to say that they are) is infantile. We haven’t even gotten to the really polarizing subjects like abortion, marital rape, harassment, workplace sexism or any of the other fights that are fought on the battleground of women’s bodies.

I’m old enough to know that there will always be people who defend the wrong thing. They are often nice people: grandparents, fathers, mothers, sisters. They do not see themselves as misogynistic, or bigoted, or homophobic, or racist - because people tend not to see that side of themselves unless forced to. Which is why representation matters.

Seeing people standing for what they believe in, matters.

It matters to me that thousands of people came to Mumtaz Qadri’s funeral and were proud to be seen there because it illustrated how very deeply rooted the problems in our cultural equilibrium really were. It matters that at Asma Jahangir’s funeral women stood along side men at the prayer, because the next time that happens, maybe it’ll matter less. It matters that women actually see other women marching in public, and yes, talking about their periods and pads and divorces if that’s what they feel they want to do. It matters because then we are all forced to confront in practice what so many people claim to support only in theory. It matters.

But you know what doesn’t matter? What men have to say about it. I realize that may come across as slightly weird considering I’ve spent the last five minutes telling you what I think, but you know what I mean.

March on.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com