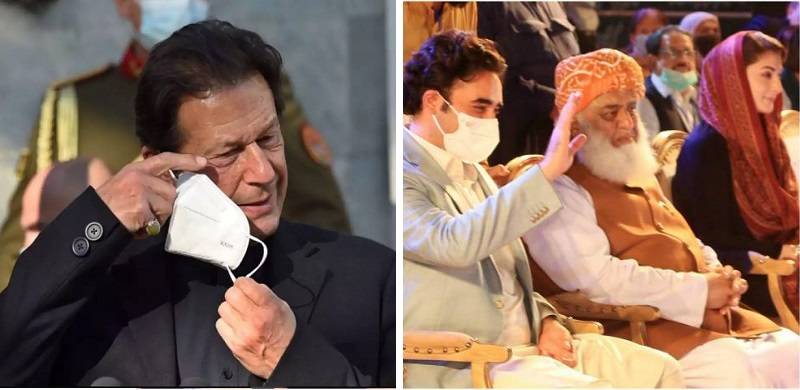

In his recent public addresses at Mailsi and the Governor’s House in Karachi, the prime minister passed disparaging comments about key opposition leaders. Epithets such as “boot-polisher,” “dacoit,” “disease” and “diesel” were bestowed on the leaders of the PML-N, the PPP and the JUI-F. Alarmingly, the premier also stated that his next primary target would be Asif Ali Zardari who was in the sights of his gun! The same bitter invective was subsequently repeated by the prime minister at a public rally in Lower Dir.

Unsurprisingly, various opposition leaders have been provoked to hit back, with Bilawal Bhutto issuing grave retaliatory threats to the prime minister, Maulana Fazalur Rehman calling him “unbalanced” and a person who has “lost his senses” and Shehbaz Sharif suggesting that Imran himself is a “boot polisher”, his sister’s sources of wealth are unexplained and that his Bani Gala estate was constructed on the basis of a glaring violation of rules and regulations.

Whereas the overall record of Pakistani politicians is unedifying when it comes to maintaining basic standards of decency of public debate, the above instances of vituperation mark a new low. In particular, it is a serious matter when a sitting prime minister makes crude, threatening and undignified references to the leaders of major political parties – which between them have garnered the votes of tens of millions of Pakistanis in the 2018 elections!

The prime minister of a country is its undisputed leader and s/he has the right and the power to set the national agenda in various walks of life. Public discourse is an arena of immense importance, and in this sphere a prime minister can either take the nation towards a model that eschews coarse language, avoids name-calling, refrains from rank abuse and unseemly polemics or s/he can lead them to a different direction in which all of these unsavoury approaches become par for the course. When a prime minister chooses to follow the latter path, this signifies an utter debasement of public discourse.

It is an open secret that Prime Minister Imran Khan has, time and again, espoused his strong desire to refashion Pakistan on the lines of the Riyasat-e-Madinah. For most ordinary Muslims, including this writer, it would be presumptuous in the highest degree to think that an exalted model of governance which is associated with the best person of mankind, our Holy Prophet (PBUH), can be tailored to accommodate our existing political paradigm with all its inherent flaws, infirmities and sordidness. However, the prime minister clearly thinks that this goal is attainable.

If one looks back at that golden age of Islam, it is undisputed that there was a key focus of that hallowed state and society on character-building, high ethical behaviour, civility of conduct and decency of debate, with the leadership serving as a beacon light for the citizens. This then begs a simple question: how do the words used by the prime minister in Mailsi, Karachi and Lower Dir square with the model of governance and public discourse enshrined in the Riyasat-e-Madinah? The answer is painfully evident.

The prime minister’s refrain has always been that the hands of the aforesaid opposition leaders are soiled with corruption, therefore his verbal harangue against them is warranted. However, on this point the prime minister would be well-advised to revisit the principle of the rule of law. Simply speaking, allegations of corruption, no matter how sensational or well-documented, remain mere allegations unless and until they are proven in a court of law and all avenues of appeal have been exhausted.

The overwhelming majority of opposition leaders have had allegations levelled against them, but not even initial convictions have as yet been recorded against them, leave alone final verdicts having been cast in stone after the completion of the appeals process. This is the prevailing situation even 3.5 years after the current government came to power on a much-vaunted anti-corruption agenda!

The prime minister needs to diagnose the reasons for the apparent failure of his anti-corruption drive and then he needs to take tangible steps to rectify the situation. But the solution does not lie in him heaping abuse and calumny on the opposition, ad nauseam. Such conduct may well endear him to his political base and strike a chord with those segments of society who are regaled by the spectacle of public figures being made the butt of abuse, coarse jokes and crude bad-mouthing, but is this really a desirable objective for a prime minister, particularly one who invokes sacred religious symbols to describe his political philosophy?

The prime minister is facing a serious no-confidence challenge. This is a constitutional means to change a government through a parliamentary mechanism. But it is not an act of conspiracy or an extra-constitutional measure. Therefore, the prime minister, too, should adopt constitutional means to frustrate the opposition’s gambit in parliament - by marshalling his parliamentary party and allies and inspiring them to stand firm in the National Assembly to defend his government on the basis of its performance in office. However, it is simply not cricket to tackle a no-confidence move by holding charged public rallies and indulging in derisive denunciation of political foes. This will vitiate the political temperature further, inject greater vitriol in our divided society and potentially lead to strife and conflict.

Step back, prime minister, and fight what you believe to be the good fight with grace, civility and honour, so that a start can be made to achieve much-needed decency of political debate.

Epilogue: In 2015-2016, the nonagenarian Dr Mahathir Mohammed, a man much admired by Imran Khan, came out of retirement to oust Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak from power due to serious corruption allegations faced by the latter. Once Najib had been defeated in the general elections, he was charged with corruption and convicted by the High Court. His appeal is still pending. But Dr Mahathir has not distorted Najib’s name or made crude references to him or otherwise made him the target of personal abuse or derision. The most he has recently said about Najib is that he considers him a criminal (which is correct since he has been convicted on corruption charges), he has brought shame on Malaysia, Malays and Islam and he is embarrassed to talk about him. This measured conduct of Dr Mahathir should make Prime Minister Imran Khan pause and re-evaluate the tone and tenor of his own public discourse about opposition politicians.

Unsurprisingly, various opposition leaders have been provoked to hit back, with Bilawal Bhutto issuing grave retaliatory threats to the prime minister, Maulana Fazalur Rehman calling him “unbalanced” and a person who has “lost his senses” and Shehbaz Sharif suggesting that Imran himself is a “boot polisher”, his sister’s sources of wealth are unexplained and that his Bani Gala estate was constructed on the basis of a glaring violation of rules and regulations.

Whereas the overall record of Pakistani politicians is unedifying when it comes to maintaining basic standards of decency of public debate, the above instances of vituperation mark a new low. In particular, it is a serious matter when a sitting prime minister makes crude, threatening and undignified references to the leaders of major political parties – which between them have garnered the votes of tens of millions of Pakistanis in the 2018 elections!

The prime minister of a country is its undisputed leader and s/he has the right and the power to set the national agenda in various walks of life. Public discourse is an arena of immense importance, and in this sphere a prime minister can either take the nation towards a model that eschews coarse language, avoids name-calling, refrains from rank abuse and unseemly polemics or s/he can lead them to a different direction in which all of these unsavoury approaches become par for the course. When a prime minister chooses to follow the latter path, this signifies an utter debasement of public discourse.

Mahathir has not distorted Najib’s name or made crude references to him or otherwise made him the target of personal abuse or derision. The most he has recently said about Najib is that he considers him a criminal (which is correct since he has been convicted on corruption charges), he has brought shame on Malaysia, Malays and Islam and he is embarrassed to talk about him

It is an open secret that Prime Minister Imran Khan has, time and again, espoused his strong desire to refashion Pakistan on the lines of the Riyasat-e-Madinah. For most ordinary Muslims, including this writer, it would be presumptuous in the highest degree to think that an exalted model of governance which is associated with the best person of mankind, our Holy Prophet (PBUH), can be tailored to accommodate our existing political paradigm with all its inherent flaws, infirmities and sordidness. However, the prime minister clearly thinks that this goal is attainable.

If one looks back at that golden age of Islam, it is undisputed that there was a key focus of that hallowed state and society on character-building, high ethical behaviour, civility of conduct and decency of debate, with the leadership serving as a beacon light for the citizens. This then begs a simple question: how do the words used by the prime minister in Mailsi, Karachi and Lower Dir square with the model of governance and public discourse enshrined in the Riyasat-e-Madinah? The answer is painfully evident.

The prime minister’s refrain has always been that the hands of the aforesaid opposition leaders are soiled with corruption, therefore his verbal harangue against them is warranted. However, on this point the prime minister would be well-advised to revisit the principle of the rule of law. Simply speaking, allegations of corruption, no matter how sensational or well-documented, remain mere allegations unless and until they are proven in a court of law and all avenues of appeal have been exhausted.

The overwhelming majority of opposition leaders have had allegations levelled against them, but not even initial convictions have as yet been recorded against them, leave alone final verdicts having been cast in stone after the completion of the appeals process. This is the prevailing situation even 3.5 years after the current government came to power on a much-vaunted anti-corruption agenda!

The prime minister needs to diagnose the reasons for the apparent failure of his anti-corruption drive and then he needs to take tangible steps to rectify the situation. But the solution does not lie in him heaping abuse and calumny on the opposition, ad nauseam. Such conduct may well endear him to his political base and strike a chord with those segments of society who are regaled by the spectacle of public figures being made the butt of abuse, coarse jokes and crude bad-mouthing, but is this really a desirable objective for a prime minister, particularly one who invokes sacred religious symbols to describe his political philosophy?

The prime minister is facing a serious no-confidence challenge. This is a constitutional means to change a government through a parliamentary mechanism. But it is not an act of conspiracy or an extra-constitutional measure. Therefore, the prime minister, too, should adopt constitutional means to frustrate the opposition’s gambit in parliament - by marshalling his parliamentary party and allies and inspiring them to stand firm in the National Assembly to defend his government on the basis of its performance in office. However, it is simply not cricket to tackle a no-confidence move by holding charged public rallies and indulging in derisive denunciation of political foes. This will vitiate the political temperature further, inject greater vitriol in our divided society and potentially lead to strife and conflict.

Step back, prime minister, and fight what you believe to be the good fight with grace, civility and honour, so that a start can be made to achieve much-needed decency of political debate.

Epilogue: In 2015-2016, the nonagenarian Dr Mahathir Mohammed, a man much admired by Imran Khan, came out of retirement to oust Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak from power due to serious corruption allegations faced by the latter. Once Najib had been defeated in the general elections, he was charged with corruption and convicted by the High Court. His appeal is still pending. But Dr Mahathir has not distorted Najib’s name or made crude references to him or otherwise made him the target of personal abuse or derision. The most he has recently said about Najib is that he considers him a criminal (which is correct since he has been convicted on corruption charges), he has brought shame on Malaysia, Malays and Islam and he is embarrassed to talk about him. This measured conduct of Dr Mahathir should make Prime Minister Imran Khan pause and re-evaluate the tone and tenor of his own public discourse about opposition politicians.