Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for the third part

One day I went for a reconnaissance mission with Captain Zamir. We visited Sulemanki where 6 Frontier Force had won a victory. They had captured on area jutting out in Indian territory. When we returned we stopped at the Divisional Headquarters. The colonel staff, Colonel S.R. Kullue (later lieutenant general), was from Probyn’s and we were invited to dinner. Soon a man wearing a greenish sweater came out. I thought he was a superseded major and why everybody was deferential to him, which they were, was only because he was so senior to all of them including the colonel staff.

The superseded major with a parting in his black hair and a bushy moustache came and sat down next to me and I started talking to him. I told him that 6 FF may have taken great risks and done a remarkable deed from their point of view, but the victory was a fluke. This, I told the attentive and indulgent superseded major, was because the Indian tanks which had been shot down had been presenting their vulnerable broadsides. This could not have happened unless the Indian armoured unit had committed a blunder. Had they known about the location of the Pakistani infantry, they would have fired at it from a distance and infantry has nothing to match the firepower of an armoured regiment. Since the Indian squadron commander did not know this, he came too near and presented his broadside and his tanks were shot. The major received this in silence and lit a Gold Leaf cigarette. ‘Let us have dinner’, he said to nobody in particular.

At dinner, since I was talking to him anyway, he invited me to sit right next to him. I did not notice that Colonel Kullue sat on the other side and everybody was quiet except myself and the major. At dinner I confided to the major that I was against all wars of aggression. He seemed very amused. Meanwhile, Colonel Kullue was giving me pointed looks which I ignored. At last he whispered to me that this was Major General Zia ul Haq, the new GOC. I then turned around and addressed him as General Zia. He beamed and seemed even more amused.

In reality, generals did not impress me since I had decided not to stay in the army forever or, even if I did, not to get promoted beyond the rank of captain. I sometimes wished they would make me the officer commanding of the Army School of Music which was in the Abbottabad valley. This officer was a captain and I assumed they did not bother him so he could ride horses and read books—the height of pleasure in my opinion. In any case, I reasoned, even the best generals were only good at war—an activity I deplored from the depths of my heart. So, even when I found out that I had been talking to the GOC, I was neither overwhelmed nor impressed. The GOC probably felt he was doing me a great favour just talking to me but I felt I had a point to make. So we parted on the best of terms with a list of misunderstandings on both sides I dare say.

During our jeep ride to the regiment, Captain Zamir, after a few grunts of disapproval, kept up a very depressing silence. He, however, provided what I consider one of the tastiest meals I have ever had. It was in the house (haveli) of a rich feudal grandee who got chicken cooked for us. It was served with curd and eaten with piping hot unleavened loaves freshly baked from the stove. It was really delicious and the bed he provided us was clean and very comfortable. Even Captain Zamir had been put at such ease that he actually attempted to smile in the morning though he wasn’t quite successful in that attempt. The driver, however, grinned like a Cheshire cat and so probably did I.

We moved from the so-called ‘plantation’ to a village near Sahiwal. This was the open Punjab countryside and I liked it. My tent was pitched near a canal and there were green fields all around and a village not far away. I now decided to complete my M.A in English literature and brought the course books from Lahore. I could read only in the day as there was no light in my tent at night. In any case I spent the evenings in the Officers’ Mess where I went with Major Saeed uz Zaman Janjua (later major general) who was my squadron commander. He was a very pleasant, good-humoured person to talk to and declared that he was fond of wine and women.

The first was much in evidence. However, the second was more of a platonic ideal, a poetic metaphor, or a conversational ploy since I never saw any woman with the would-be Don Juan except his wife. One day I hinted at my suspicion that all the women of his conversation were just hypothetical. At this he laughed heartily but still provided no empirical evidence at all of anything in this line. For that matter the ‘wine’ too was a metaphor for beer and whisky. He was a jolly good fellow and I was fond of him. He never questioned me about my ‘pacifism’ which was surprising since he himself was given to much cavalry bravado much like our friend Tambal. I had both great liking and respect for Major Janjua and I only hope there are people like him serving in the army. They make everybody’s life so much easier. The other squadron officers were Asad and Sohail whom I have mentioned earlier.

Exercises on tanks in the hot weather are hardly fun. However, Major Saeed uz Zaman Janjua made them as enjoyable as possible. One evening, while worshipping Bacchus, he asked me whether I would be game for kidnapping the doctor. I said I was and so did Asad. So off we went to abduct the medical officer of the regiment who was as averse to military life as a Buddhist monk. The captain was in his tent and we approached stealthily with blankets. I do not remember our having actually used those blankets but I do remember having an uproarious time with the doctor laughing quietly at our antics. Those who went to leave him to his tent got lost and returned in the early hours of the morning. Such things put colour in our tough lives.

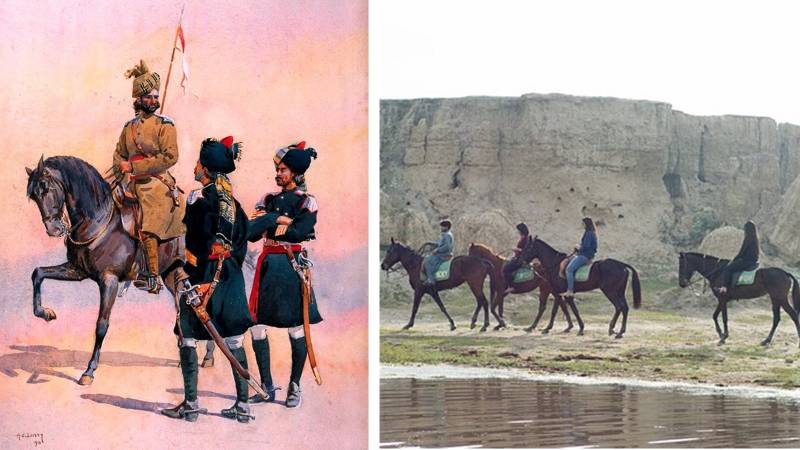

Another thing which put colour in my life was riding. I sometimes got a white horse from the village and rode it to Jerry’s unit which was many miles away. Jerry used to talk about migrating to America for good and I always told him that the army gave many more comforts and privileges than any other way of life at least in Pakistan. Jerry laughed at me since I myself wanted to leave the army.

‘But I am leaving for reasons of conscience’, I told Jerry.

‘What conscience’, he queried mockingly.

‘I am anti-war. At least against wars of aggression and an army officer is not supposed to decide which war he will fight and which not. Hence, I should resign my commission. It is the only decent thing to do’, I said in exasperation.

‘Oh come on Titch!’, he said ‘There won’t be a war’.

‘You don’t understand’, I expostulated.

‘We know you are clever. Now have some tea’.

This is how the conversation would go. As I was really fond of Jerry I went again and again to see him since I had no other close friend.

Sometime we went for movies to the nearest city. Once, while coming back I got lost. It was dark and I sat under a tree in the vast plain of the Punjab while jackals howled and dogs barked around me. Then I followed a light and it was a guard of my regiment. The guard challenged me and it was with tremendous relief that I said: ‘Friend’, The comfort of the tent was minutes away.

From the Sahiwal area, Probyn’s went to Bahawalnagar—not to the town but to a guava grove outside it. My tent was right in the midst of the guava trees and it was boiling hot. I still slept on the stretcher and the mess was far off. From here our squadron was sent for the 23 March parade in Rawalpindi Race Course. It was 1973 and I was happy that I found some time to meet my family. I commanded a troop of tanks during the march past and wrote a number of very radical essays which did not survive. In those days I did not show my writings to anybody. I did not publish it either. I just wrote it and put it away.

Later that year (1973) we came back to Multan Cantonment and then I took leave to appear in the MA examination of the Punjab University. My examination centre was in Pindi and I took the examination while staying at my house. In the August of that year I opted for the Advanced Equitation Course in the Remount Depot Mona which is near Sargodha.

Before the course I had bought my first car. It was a Fiat 600 of 1961 which had belonged to Air Marshal Asghar Khan but he had gifted it to his son Omar. Omar wanted a new, big motorbike. I had helped Asad get a loan for this motorbike from Habib Bank as my brother-in-Law, Aizaz Khan (d. 2023), husband of my cousin Surraiya Baji, was the manager of the Cantonment branch of this bank. I had also taken such a loan which had enabled me to buy a Lambretta scooter. I had bought this scooter in Pindi from the army canteen and Ahmad had accompanied me to Tariq Ahsan’s house. As in the case of my first bike ride with Ahmad, we fell several times but made it to Islamabad in one piece. So it was this scooter I sold, and to this money I added money from my mother, a loan again, and thus bought the car for Rs6,000.

Exercises on tanks in the hot weather are hardly fun. However, Major Saeed uz Zaman Janjua made them as enjoyable as possible. One evening, while worshipping Bacchus, he asked me whether I would be game for kidnapping the doctor

I did not think of applying for a driving licence and started driving the car straightaway. However, I drove this contraption by trial and error—mostly the latter! That I had no major accident was something of a miracle but the car kept running out of petrol every now and then and at the oddest of places. This, however, was not the car’s fault but mine since I put only half a gallon at the best of times and drove about without checking the fuel tank.

The salary of a lieutenant in those days (1973) was only Rs550 with allowances. This was, in fact, the starting salary of all Class 1 officers, civil or military, though I am sure the civilian officers of the CSP cadre had hidden perks. Most of the perks which army officers got, including air travel at half price, came later. This salary was really inadequate for maintaining a car but this was a lesson which I had to learn the hard way. Even so, with little money, no driving license and inadequate driving skills, I decided to drive the car all the way to Mona. Such confidence could only be a product of belonging to the officer corps of the army since now, as a civilian, I cannot even think of it. However, though I did reach Lahore without too much trouble, I booked the car for Mona by train there and travelled myself on the fast train.

Mona was a large horse depot and I loved its open lawns, fields, riding schools and polo grounds at first sight. Cars were not much in evidence inside the depot and officers went about on cycles, horses and horse-driven, old fashioned carriages. The officers’ Mess was an old-fashioned, snug little bungalow with a nice green lawn in front of it. Our Bachelor Officer’s Quarters were near it and they too were situated in acres of land and had a bucolic and serene air. M

y spare time was spent mostly in reading. I remember reading the novels of D.H. Lawrence in those days. I also enjoyed the company of other officers. Among the officers who did the course with me I remember Lieutenant Amjad Kamal Butt (later major) and Captain Nangiana (later colonel). Captain Nangiana was from Sargodha and his family owned land so he was quite at home in Mona. Of course, being from a feudal background and an army officer to boot, he did not agree with my views about personal freedom, individualism, peace and egalitarianism. However, he was a genial and gentlemanly person so we remained on excellent terms. Butt was a very intelligent man whose company I enjoyed very much but he too did not believe in my liberal ideas. Again, this created no problem and we enjoyed long sessions of banter. I told him that he had his eyes on the throne and for this he would have to be a general.

‘But this is a democracy’ he protested.

‘Not really. The army will rule again. And if you are not the COAS you would be not in the run for the top dog’.

‘So, you mean I must slave away and slave away with that end in view’.

‘Obviously—if you call being served by waiters and consuming gallons of beer slaving away, then YES.’

‘And you?’

‘I don’t have to bother. I won’t be in the run. I am o.k with books and horses.’

Amjad suggested lewd additions and get a rap on his head for his pains.

We got up early in the morning and went for riding. After a few hours we came back ravenously hungry for breakfast. People ordered as many as six extra eggs on top of the two eggs they gave us anyway. After this we went for classes about how to look after horses and even brushed and saddled the animals. Then came lunch and a bit of rest.

In the evening we again went for riding for three hours. Late evenings after sunset were free. We had walks and I used to drive my little car to Sargodha with friends. But at about seven rupees a gallon, petrol was so expensive for me that such indulgence could not be very frequent. As a further drain on my income, the car developed faults.

One day I found that its brakes had failed completely. Amjad told me that the nearest place where I would find a mechanic was Jhelum. He also volunteered to come with me if I let him also drive the car. So, we drove off on the mud path on the bank of the Jhelum canal. At first, we went slow but this was so tedious that we increased the speed. The car was slowed down by shifting gears and using the hand brake in a clever combination of which we were justly very proud.

Anyway, caring for none of the traffic on the narrow road and the suburbs of the city, we reached Jhelum only to find the city closed on account of something! Now we had a choice between going back to Mona or driving on to Pindi. We were reckless enough to choose the latter alternative though it meant driving on the main G.T. road. Whenever we had to stop we slowed down and looked for a place where we could drive the car away from the road. So, driving into bushes; into sand and mud; into piles of loose stones; into fields – we reached Pindi. Throughout the way we were joking and shouting and telling each other – whoever was driving—what to do. It was a miracle we did not have a major accident. But such is the optimism of youth that we did not fully appreciate the risk we had taken.

As for the course, I was easily the best rider in the course to begin with but I had no ambition to top the course. Thus, I did not bother too much about the instructor – Dafadar Nazar. He told me to ride with long stirrups but I preferred short ones. For being so pig-headed I knew I could not top the course. This only made me more careless so I later rode with no stirrups at all which was against all orders. Ustad Nazar confessed my excellence in riding but he cursed my independence.

To make matters worse, I did not bother about writing down the instructional lessons which had to be committed to memory. These were written in Urdu in a register and even the deviation of one word was not tolerated. When my turn came I gave the lesson entirely in my own words in Urdu peppered with words of English. Dafadar Nazar almost had a fit but even he did not fail me since the lessons were clear and simple to understand. And so the course went on. Not surprisingly, Captain Nangiana topped it though everybody, including Nangiana himself, acknowledged me as the best and the most fearless rider they had seen.

One day Captain Nangiana invited myself and Butt to his ancestral house (haveli) near Sargodha. So off we went on my little blue car which did not let us down. The haveli was made of stone as far as I remember though other houses in the village were of mud. The Nangianas were big landlords so they were wealthy and we were given sumptuous dishes in keeping with traditional old-world hospitality. We also rode his village horses which were much smaller than the thoroughbreds we had in Mona.

Unfortunately, one of the ponies got stuck in a pool of slimy mud and the more it made efforts to get out the more it sank. Right before our eyes the horse was sinking. And as it sank up to the withers it started shaking and even gave up struggling. By this time someone brought sheets of some hard material, perhaps silk or just cotton, and I and a few others stepped into the mud putting other sheets and a lot of grass or hay under out feet. Somehow, we managed to put that sheet under the horse and got out just before we too got stuck. This time we did manage to get the horse out. It stood shaking with its head down till somebody led it towards its stable.

We also went for wild bear hunting but I was appalled at the cruel practice of driving the wild boar, including little piglets, to the hunter. I was on horseback armed with a spear and I deliberately let the sow and the piglets escape the hunters. After this experience I never went hunting or shooting again. I remembered how I had shot dogs as a boy in PMA and thoroughly regretted this needless cruelty. From that day onwards I never held a spear or gun in my hand to kill animals.

One day towards the end of the course I received the good news that I had passed my M.A in English Literature and that, having a good second division, had done unexpectedly well. I also came to know that, having something like three marks less than first division which used to be at 60 percent marks, I stood third in the whole university that year. The candidate who had stood first was a girl with the name of Minnie Serena and I do not know if she did get a first or a good second. Well, because she was a girl, my friends found it fit to pull my leg.

‘What kind of cavalry officer would get beaten by a girl’, said Tipu (later brigadier) in derision.

‘One would challenge her for dishonouring the cavalry’, added another.

‘Well’, said Captain Nangiana with a smile ‘no gentleman can fight a duel of honour with a lady’.

Everybody agreed with that though Amjad muttered something on the lines that this applied only to gentlemen for which I gave him a well-deserved rap on the head. In the end everybody decided that I would have to live with this eternal disgrace and the only punishment of the offender should be that she should become a venerable aunty and that was that. While, not a single one of my friends acknowledged at that time that standing third in the university as a private candidate was something of an achievement, they nevertheless and quite brazenly, still asked me for a treat. I pointed out that all they had done was to try to make me ashamed of it. They countered that the shame remained intact and valid as a girl had beaten me but that did not mean it was not an achievement so a treat was due. I refused but eventually had to yield to their pressure and the treat had to be given in Sargodha in the PAF officers’ club there. Of course, this meant that I had to borrow the money from the same people who enjoyed the treat.

At last, on a cool and crisp winter day the course finally came to an end. We all got ready to disperse. As usual I was terribly short of cash and the idea of driving the car or putting it on the train was nightmarish to say the least. In that condition, right on the last day of the course, Nangiana’s cousins came and offered ready cash for my car. I was tempted since the money was enough to repay all my loans and still leave me with what I thought was a king’s ransom. I do not remember how much they paid me but it seemed a lot to me. But I did regret parting from the car. Anyway, I came back to Multan without it.

(to be continued)