“Har cheez bhula di jaayegi

Yadon ke haseen butkhane se

Har cheez utha di jaayegi

Phir koi nahin yah poochhega

Sardar kahan hai mehfil mein”

(Every memory will be erased from the beautiful temple of memories

Every single thing will have gone

Then, no one will ask:

Where is Sardar in the Soirée?)

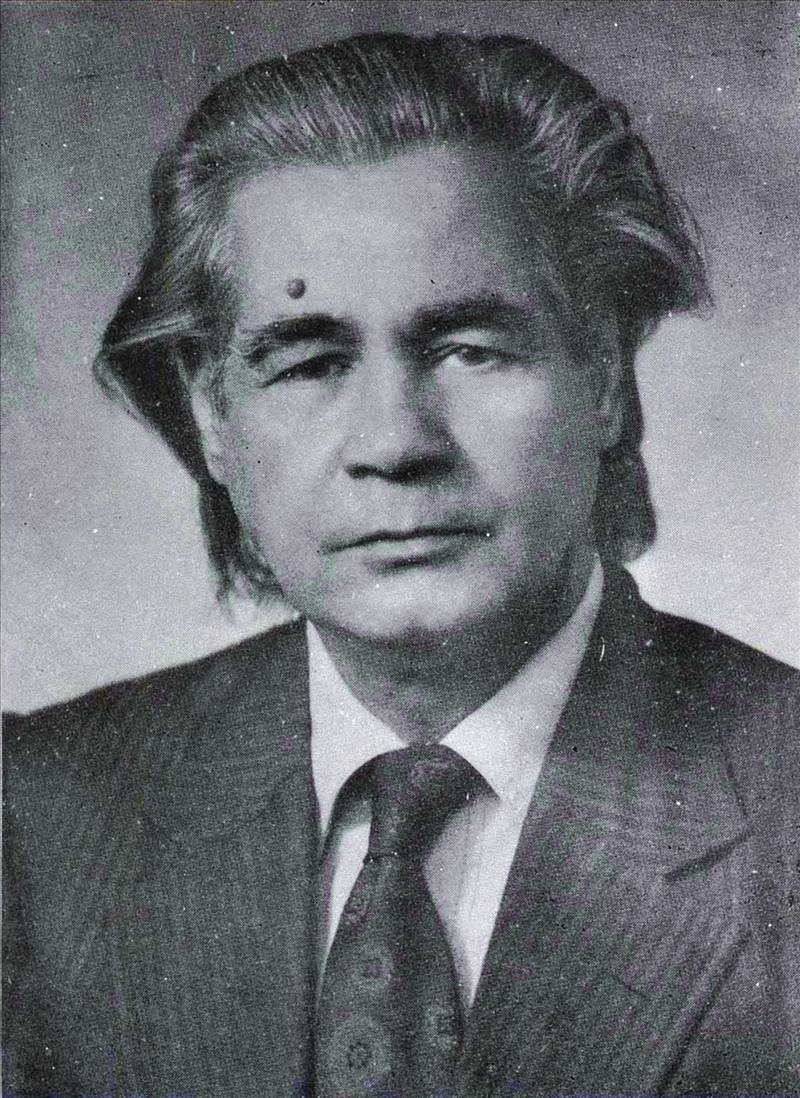

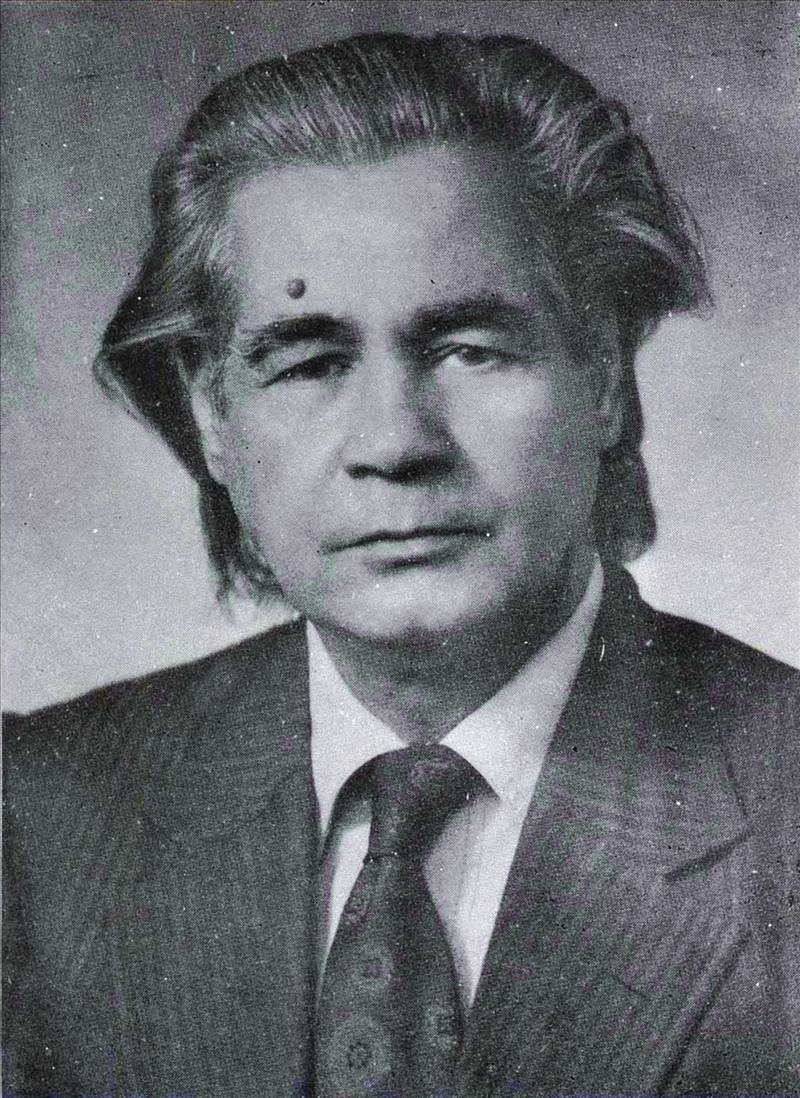

For some reason, the writer, orator, poet, short-story writer, dramatist, critic and filmmaker Ali Sardar Jafri, who passed away in Mumbai 20 years ago this year on the 1st of August, never received his due as a poet. Perhaps it was due to his programmatic verses and his overt association with the Communist Party of India. In his later years, he experienced some recognition as a poet who wrote optimistically about Indo-Pak relations. When Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee took a bus journey to Pakistan in 1999, the following four-liner by Jafri was played on its PA system, and became quite the rage for a while:

“Tum aao Gulshan-e-Lahore se chaman bardosh

Hum aayen subh-e-Banaras ki raushni le kar

Himalaya ki havaaon ki taazgi le kar

Aur us ke baad yeh poochenge kaun dushman hai?”

(Come bearing the fragrant garden of Lahore

And we will bring the light of a Banaras morning

And the fresh breeze from the Himalayas

And then let us ask: who is the enemy?)

Jafri is not only among the founders of the Progressive Writers Movement but he raised the standard of Progressive literature with his sensual labours; and thus created new meanings and facets in it. He began his career as a fiction writer, but later moved to poetry. He also wrote a few plays for the Indian People’s Theatre Association.

He was subjected to periodic imprisonment twice: for the first time by British colonial authorities during the Second World War in 1939, for the crime of making a speech at the height of opposition to what was then seen by the communist movement as an imperialist war, akin to the First World War.

In those days, the custom of restricted house-arrests had not become prevalent, in fact, a case was established even against political prisoners in court and punishment was given for a fixed period. The charge-sheet against Sardar was so flimsy that had he fought the case, he would have definitely been released. But respecting the longstanding political tradition of the country, he said in full court that “we neither accept this court nor its law, therefore the question of presenting a defence does not even arise.” He was sentenced to six months of hard labour. He spent a few days in Lucknow, then was sent to Banaras.

When Sardar was released, the nature of the World War had changed due to Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union. Crushing Malaya and Burma, the Japanese forces had reached the borders of Assam, in fact Calcutta had even been air-bombed. This was not the time to sit on the fence.

So, when the training of guerrilla units began in Lucknow, Sardar also joined it and began to write anti-fascist dramas and speeches for the radio. In those very days, the mushaira was held, which Sardar Jafri has mentioned in his book Lucknow Men Paanch Raaten (Five Nights in Lucknow).

And then again – in a moment that reminds us of Frantz Fanon’s account of the betrayal of the moment of decolonization by local elites – Jafri was arrested by the government of independent India in 1949 for espousing the cause of socialism, joining his colleagues like Faiz and Sajjad Zaheer who had suffered similar incarceration in Pakistan.

Like a good communist, he also aroused the ire of religious fundamentalists, and was subjected to death threats in the 1980s when he came out against the treatment of divorced women under the Muslim Personal Law. His opposition to the infamous Muslim Women’s Protection Act in 1986 earned him the ire of Muslim communalists; college students of that period still remember watching him being shouted at, slapped and garlanded with chappals by goons – a moment that further politicized some of those young witnesses against the atmosphere of rapidly increasing communalism in India. However, in the end, we must remember that Jafri led a celebrated life, having had the Jnanpith award bestowed on him in 1993. In 2013, on the occasion of his birth centenary, a website was inaugurated in his honour.

(to be continued)

All translations from Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

Yadon ke haseen butkhane se

Har cheez utha di jaayegi

Phir koi nahin yah poochhega

Sardar kahan hai mehfil mein”

(Every memory will be erased from the beautiful temple of memories

Every single thing will have gone

Then, no one will ask:

Where is Sardar in the Soirée?)

For some reason, the writer, orator, poet, short-story writer, dramatist, critic and filmmaker Ali Sardar Jafri, who passed away in Mumbai 20 years ago this year on the 1st of August, never received his due as a poet. Perhaps it was due to his programmatic verses and his overt association with the Communist Party of India. In his later years, he experienced some recognition as a poet who wrote optimistically about Indo-Pak relations. When Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee took a bus journey to Pakistan in 1999, the following four-liner by Jafri was played on its PA system, and became quite the rage for a while:

“Tum aao Gulshan-e-Lahore se chaman bardosh

Hum aayen subh-e-Banaras ki raushni le kar

Himalaya ki havaaon ki taazgi le kar

Aur us ke baad yeh poochenge kaun dushman hai?”

(Come bearing the fragrant garden of Lahore

And we will bring the light of a Banaras morning

And the fresh breeze from the Himalayas

And then let us ask: who is the enemy?)

Jafri is not only among the founders of the Progressive Writers Movement but he raised the standard of Progressive literature with his sensual labours; and thus created new meanings and facets in it. He began his career as a fiction writer, but later moved to poetry. He also wrote a few plays for the Indian People’s Theatre Association.

He was subjected to periodic imprisonment twice: for the first time by British colonial authorities during the Second World War in 1939, for the crime of making a speech at the height of opposition to what was then seen by the communist movement as an imperialist war, akin to the First World War.

In those days, the custom of restricted house-arrests had not become prevalent, in fact, a case was established even against political prisoners in court and punishment was given for a fixed period. The charge-sheet against Sardar was so flimsy that had he fought the case, he would have definitely been released. But respecting the longstanding political tradition of the country, he said in full court that “we neither accept this court nor its law, therefore the question of presenting a defence does not even arise.” He was sentenced to six months of hard labour. He spent a few days in Lucknow, then was sent to Banaras.

When Sardar was released, the nature of the World War had changed due to Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union. Crushing Malaya and Burma, the Japanese forces had reached the borders of Assam, in fact Calcutta had even been air-bombed. This was not the time to sit on the fence.

So, when the training of guerrilla units began in Lucknow, Sardar also joined it and began to write anti-fascist dramas and speeches for the radio. In those very days, the mushaira was held, which Sardar Jafri has mentioned in his book Lucknow Men Paanch Raaten (Five Nights in Lucknow).

And then again – in a moment that reminds us of Frantz Fanon’s account of the betrayal of the moment of decolonization by local elites – Jafri was arrested by the government of independent India in 1949 for espousing the cause of socialism, joining his colleagues like Faiz and Sajjad Zaheer who had suffered similar incarceration in Pakistan.

Like a good communist, he also aroused the ire of religious fundamentalists, and was subjected to death threats in the 1980s when he came out against the treatment of divorced women under the Muslim Personal Law. His opposition to the infamous Muslim Women’s Protection Act in 1986 earned him the ire of Muslim communalists; college students of that period still remember watching him being shouted at, slapped and garlanded with chappals by goons – a moment that further politicized some of those young witnesses against the atmosphere of rapidly increasing communalism in India. However, in the end, we must remember that Jafri led a celebrated life, having had the Jnanpith award bestowed on him in 1993. In 2013, on the occasion of his birth centenary, a website was inaugurated in his honour.

(to be continued)

All translations from Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com