I was there when, in the first week of October 1993—a few days before parliamentary elections— Nawaz Sharif told a jam-packed Liaquat Bagh that after coming to power he wanted to normalise relations with India. The crowd was euphoric, and there was a palpable sense of victory in the air. Nawaz Sharif had just been ousted from power after a confrontation with the then-military-backed President. We were sitting close to where Sharif stood in front of the crowd several feet above the ground level—he looked tired after a long and exhausting month of electoral campaigning in Central Punjab, his stronghold, but he was over-enthusiastic in conveying his political agenda to his constituency, the Punjabi middle class. Murree Road was blocked from Moti Mahal Cinema till Faizabad as droves of Sharif's supporters continued to arrive to listen to his concluding election speech before the country went to polls on October 6, 1993.

Sharif was employing the well-known argument that Pakistan and India should spend more on bringing prosperity to their respective people instead of spending on their militaries. This was Nawaz Sharif's first articulation of his India policy, which he became known for in later years. And it was a gamble as well: Central and Northern Punjab—the recruiting grounds for Pakistan Armed Forces and a hotbed of anti-India feelings could have turned against Nawaz Sharif's Muslim League in the parliamentary elections. Well, they didn't. His party secured 73 seats in the national assembly and emerged as the second largest party, coming second only to Benazir Bhutto's Pakistan People's Party (PPP) which secured 89 seats. Nawaz Sharif's performance showed that the Punjabi middle class —most of which resided in Central and Northern Punjab at that time— would not react negatively to any suggestion of normalising relations with India. In the wake of the 1993 parliamentary elections, Nawaz Sharif could safely have claimed that his political agenda of normalising relations with India was approved by the electorates. It was a kind of, "Nixon goes to China Syndrome" that seemed to have played out in those parliamentary elections. A Punjabi—Kashmiri hardline political leader, who had in the past thrived on anti-India feelings, had then decided to pursue peace with India.

Wishes, desires, and dreams in their raw form cannot be transformed into workable foreign policies. For a change in foreign policy, you need to devise a plan. And if a change in foreign policy is as dramatic as moving away from half a century of antagonistic relations with traditional adversaries like India, then the ruler must consider how the change in policy will affect power relations within the country

The 1993 parliamentary elections did not bring Nawaz Sharif to power. He had to wait until another parliamentary election in February 1997 for that. After coming to power, Nawaz Sharif followed on his promise and pursued a peace agenda with India. However, it was not the public reaction that posed a problem for the then-Sharif government. It was a lack of planning, absence of domestic consensus among different power centres in Pakistan and Sharif's complete inability to think and act strategically on the issue of normalisation with India that could have impacted the domestic power structures of the country. Wishes, desires, and dreams in their raw form cannot be transformed into workable foreign policies. For a change in foreign policy, you need to devise a plan. And if a change in foreign policy is as dramatic as moving away from half a century of antagonistic relations with traditional adversaries like India, then the ruler must consider how the change in policy will affect power relations within the country.

At the time of the Lahore Summit, which brought the then-Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to Lahore in 1999, the civil-military relations in Pakistan were far from stable. Nawaz Sharif had just forced a Chief of Army Staff (COAS) to resign and had appointed a man of his choice (General Pervaiz Musharraf) to be the new army chief. The military's ranks and files were not incredibly happy with the way their army chief was forced to resign. Public discourse related to that period revolves around the issue of whether the military had informed Sharif about intruding into Kargil or not? We have never debated whether Nawaz Sharif, as prime minister, took the then-military leadership into confidence about his new policy towards India and normalising relations? Our radical political discourse usually considers it unnecessary for the prime minister to consult the military as it is deemed his prerogative. Here, Nawaz Sharif's inability to work out a consensus among the power centres could be described as his single biggest mistake, which led to the failure of his India policy in 1999. If you do not develop a consensus over an earth-shattering policy such as normalisation with India that could potentially restructure power relations in your society; you are committing a fatal mistake.

The primary reality about different power centres in Pakistan and their mutual relations is the fact that these power centres are insecure vis-à-vis each other. They doubt each other's intentions. And many times in the post-Musharraf period, these power centres conspired against each other on the smallest pretext

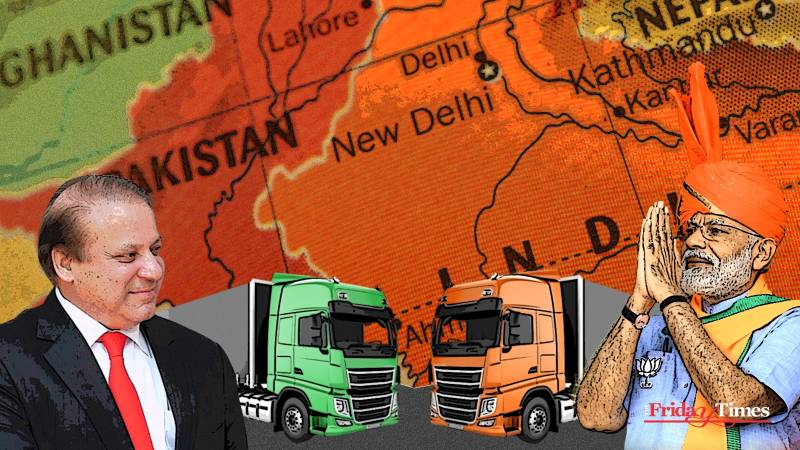

Nawaz Sharif repeated the same mistake in December 2015 when he hosted Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Lahore at his private residence. This again rattled his relations with the military establishment, which took it as another attempt by Sharif for a solo flight. In the absence of institutional consensus to back Sharif's wish to normalise relations with India, hosting the Indian prime minister at his private residence without even senior state functionaries present in meetings between the two premiers raised alarm bells in Rawalpindi. And again, military leaders started to develop doubts about Nawaz Sharif's intentions. Within two years, he was ousted from power. The primary reality about different power centres in Pakistan and their mutual relations is the fact that these power centres are insecure vis-à-vis each other. They doubt each other's intentions. And many times in the post-Musharraf period, these power centres conspired against each other on the smallest pretext, especially when they developed doubts about each other's intentions.

Nawaz Sharif has twice faced this situation in his political career. First, when he invited Vajpayee to Lahore, the military pursued a parallel India policy when it launched a secret Kargil adventure. Second, when Nawaz Sharif invited Modi to his private residence in Lahore, this again led the military establishment to launch a "get Nawaz Sharif" operation, which culminated in his ouster from power.

On the eve of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation's Summit in Islamabad, former prime minister Nawaz Sharif reportedly once again expressed his wish that they (Pakistani prime minister or government) would be meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narender Modi soon. "It would have been a great thing if PM Modi had also attended the SCO summit here in Pakistan. I do hope that he (Modi) and us will have an opportunity to sit together in the not-so-distant future," he told Indian journalist Barkha Dutt in Islamabad.

Nawaz Sharif's assertion is, again, simply a pious wish that can hardly be transformed into a workable policy. And there is a potential danger that, once again, a pious wish from Nawaz Sharif would prove too divisive for Pakistan's power structure

Nawaz Sharif's pious wish is again not backed by institutional consensus in Pakistan. Unlike his predecessor, COAS General Syed Asim Munir does not seem enthusiastic about normalising relations with India. His predecessor, General (retired) Qamar Javed Bajwa, showed enthusiasm for reducing tensions with New Delhi.

Another key aspect is that there has been no policy debate in the media or in political circles to examine the options available to the Pakistani government in the fast-changing geo-political and security environment of the region. There is not even a single study in the official or non-governmental sector about how changing regional security and political environment would affect the prospects of improving relations with India. Yet, suddenly and unexpectedly, Nawaz Sharif has made a statement about improving relations with India. Nawaz Sharif's assertion is, again, simply a pious wish that can hardly be transformed into a workable policy. And there is a potential danger that, once again, a pious wish from Nawaz Sharif would prove too divisive for Pakistan's power structure. Thus, signs of trouble in civil-military relations have already started to appear in Islamabad and Rawalpindi.

Pakistan-India relations are mostly defined by the military content of their relations—the political leaders of the two countries are not on talking terms. Trade relations between the two countries are minimal. Business and commercial collaboration is nonexistent. We barely even play cricket with each other. The Pakistan military is a dominant player in politics, and adversarial relations between the two countries at the military level allow the Pakistani military to dominate the power structure in Pakistan. India is militarily superior and is a threat to Pakistan's survival, which is the argument that supports continued higher levels of military spending in Pakistan. In India, on the other hand, the military lives under complete civilian supremacy. In the last two decades, India's economic miracle has allowed the Indian government to spend an exponentially high percentage of its GDP on defence and military without causing any economic and political instability in the society. Pakistan's high military spending has pushed it close to the brink of financial bankruptcy. The power centres in Pakistan, in this context, exist in a highly insecure environment with the result that they perceive any move on the part of rival power centres that could disturb the precariously held equilibrium to be a threat to their existence or their share within the small and ever-shrinking financial and resource pie. In this context, Nawaz Sharif's pious wish to normalise relations with India often proves to be a highly destabilising factor in Islamabad's power politics.

Now, the Americans do not seem interested in bringing the two countries to the negotiating table. To the contrary, Americans are busy propping up the Indian military as a counterweight to China in the region

What started in December 1993—at that time, Nawaz Sharif appeared to look like a statesman for thinking out of the box on the question of relations with India—as a pious wish that has time and again proved to be the cause of national disasters like Kargil and coups and counter coups.

The times, though, have changed. We do not have any method to discern whether Nawaz Sharif realises how dramatically different the international and regional geo-political environment has become since he last made a full-fledged diplomatic attempt to normalise relations with India in 1999. For instance, at the time of the then-Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee's visit to Lahore on a bus, US diplomats stationed in the region played a critical role in establishing initial contacts between Indian and Pakistani Prime Ministers' offices. The US diplomats, who were active in attempts to shape Pakistani and Indian nuclear doctrines and strategies in the wake of nuclear tests by the two countries, were also instrumental in shaping the agenda and content of the Lahore Summit. Now, the Americans do not seem interested in bringing the two countries to the negotiating table. To the contrary, Americans are busy propping up the Indian military as a counterweight to China in the region—a policy which could prove to be highly destabilising for South Asia.

Secondly, at the time of the Lahore Summit, there was a considerable body of opinion within India that was interested and was lobbying New Delhi to normalise relations with Pakistan. This is no longer the case. The Indian public opinion has turned highly anti-Pakistan in the wake of the Mumbai attacks. Thirdly, it is not simply the Americans who want to prop up India as a counter to China. Japan, Australia, and a host of other countries are flirting with the idea that India could mitigate the adversarial effects of the rise of China in Asia. Fourthly, India's rise as an economic powerhouse has transformed the perceptions of its political elites about regional security. It is not surprising that Indian military and political elites have started flirting with dangerous military and political concepts and doctrines vis-à-vis Pakistan.

The fact that the military dominates and controls the mechanics of its political system has stunted Pakistan's political, social, and economic growth

Nawaz Sharif, however, seems to be still living in the 1990s. His views about relations with India appear too naïve. There seems to be no realisation that during the last two decades, India has taken a great leap forward. It is all set to become the third-largest economy in the world by the middle of the century. Pakistan, on the other hand, has lagged. It is almost bankrupt, and there are questions about its continued financial viability without international help. Its terrorism and militancy problems mean that it is likely and certain that it will not be able to achieve its economic potential in the next two decades. Pakistan's highly unstable political environment and absence of political norms and trade will force it to continue the path of a highly unstable country. The fact that the military dominates and controls the mechanics of its political system has stunted Pakistan's political, social, and economic growth.

The choice for Pakistan is either to continue on the self-destructive path of confrontation with India and lose any chance of attaining economic growth at a rate that could sustain the economic aspirations of its ever-growing population. The second choice is to embark on a diplomatic track that suits its reduced economic and political weight in the region as well as internationally. In both cases, the days of substantial and sustained dialogue with India that would be supported by the international community are over.