In a political environment where anti-military posturing used to pay political dividends, Pakistan’s political elite’s mindset is fossilized. To be perceived as an anti-military establishment political leader who is in defiance of the incumbent intelligence and military leaders was (maybe still is) considered a great success in this environment. You are perceived as a victim of the military and intelligence establishment’s highhandedness and your public diatribes against the military and its interference in political affairs are counted as a vote attracting strategy. A flawed and immature understanding and appreciation of political realities are at the basis of this posturing.

Historically, the masses in our region have had a romantic relationship with power and those who wield, exercise or oppose it. Anti-military posturing stems from a political understanding that since the people hold those in power responsible for their hardships, they will support anyone who confronts the powers that be. All this is pure romance and naïveté. In the post-Zia period, this strategy has been adopted by every successful popular leader as the shortest path to build and construct their persona as a larger than life political figure. Anti-military posturing has become therefore the dominant strategy in political discourse at the moment.

The rise of this strain of thinking corresponds directly with the military’s own rise as a dominant player in the power game. This speaks volumes about the barrenness of our political discourse. Anti-military posturing’s salience in the political discourse also reflects the narrowness of intellectual and mental capacities among our political elite. Consider this: at the heart of the civil-military conflict in our society are the procedural and turf wars in our polity that are routinely fought between incumbent governments and military leaders. This unfortunately means anti-military posturing hardly covers the enormity of economics, political and social problems that Pakistan society faces. Anti-military posturing might appear to be a strategically sound electoral strategy, but it can hardly solve Pakistan's governance problems.

We can easily conclude that civil-military tensions or occasional conflicts are hardly a suitable tool for explaining the problems of governance our society is facing. Administrative decay, the dwindling capacity of the state to act at appropriate times and in emergency situations, the lack of capacity of political leaders to carry out administrative tasks of the state could hardly be explained in terms of civil-military tensions. The economic meltdown and inability of almost all political leaders to tackle issues related to internal security are other problems our society and polity are facing.

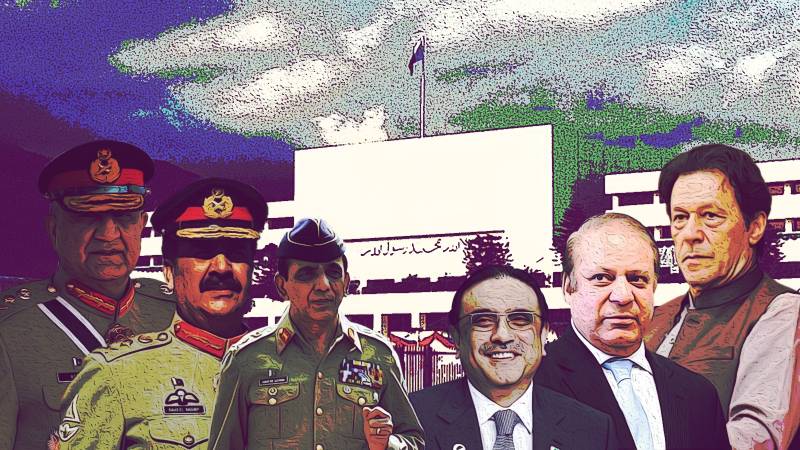

Both major political leaders in our system—Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan—have stories to tell as far as the military's highhandedness is concerned. Our 40 plus news channels have transformed the individual stories of these leaders into a melodramatic soap opera. When we believe the stories these two leaders narrate in private meetings, we have to conclude that they have been treated badly. And those who are interested in the melodrama must devote time to listen to their ordeals. What, however, appears quite strange is the fact that these leaders want to grab the attention of the whole nation and then narrate their stories, wasting in the process the nation's precious time.

It would not be an exaggeration to say we as a country and nation are on the verge of collapse. A vibrant political leadership would at this critical moment come up with some plans for the revival of the economy and would throw around some ideas as to how to deal with the rising tide of violence in our North West and South West. In fact, our leadership is not even discussing these pressing problems. What we see in our midst is a reflection of that fossilized mindset — a set of ideas fossilized in their obsession with anti-military posturing. Imran Khan and his party openly display this mindset, while in the case of the PML-N and Nawaz Sharif, this mindset is somewhat dormant, but could be revived at an appropriate time.

There are two problems with anti-military posturing. Firstly, anti-military posturing will vitiate political elites’ relations with the military and governance will become a problem in case any one of them come to power in the wake of the forthcoming parliamentary elections. Secondly, these political leaders don't have the capacity to rule Pakistan independent of the military's support. Pakistan’s internal security situation is turning into a nightmare and our political elites have zero capacity to deal with this situation. There are two indicators of this reality. Firstly, political elites in the past have behaved in a way which reflects their fear, at the level of personal security, of taking on the Tehreek-e-Taliban using military tools, and have also demonstrated that they lack the motivation to deal with the Tehreek-e-Taliban as an entity they have to militarily crush. Secondly, their flawed understanding of the military nature of the terror threat Pakistan is facing is a major obstacle in the way of the civilian political elite assuming a leading role in state affairs.

If they continue in their ways, this political elite will never be able to put forward a comprehensive plan to tackle the myriad of Pakistan’s problems. Remember that the civil-military imbalance and conflict are not the whole of our governance problem. They are only a part.

The political elite’s anti-military posturing in such a situation is nothing more than a primetime soap opera, full of histrionics - but with no meaningful content. The Pakistani military’s existing hegemonic dominance of the political system could be explained as a post-Musharraf political reality, which in practical terms would mean that the military never completely relinquished the baton of power. Under the first civilian President and PPP co-chairman Asif Ali Zardari, the parliament facilitated the transition from a uniformed President to a parliamentary form of government headed and steered by a democratically elected Prime Minister. This was the front story.

In reality, the office of the Chief of the Army staff emerged as a parallel executive authority in the country under three successive Army chiefs - General Ashfaq Pervaiz Kiyani, General Raheel Sharif and General Qamar Javed Bajwa - who served in the post-Musharraf period. The office of Army chief continued to make decisions about when, where and how to use force against militant and terror groups and continued to act as diplomat-in-chief. That the Army chief acted in these roles was clear for everybody to see. Besides these roles, it is generally believed that Army chiefs in this period have decisively influenced the process of making or breaking of democratic governments. The fact that the military also dominates the coercive machinery of the state, in this period, is also plain to see. However, this is a truth that we as people never put into words in plain language. This is often stated in coded language.

But occasionally, we get confirmation of what can ostensibly be described as conspiracy theories from the formerly powerful and mighty. For instance, General Bajwa’s assertions that he and other military officials were instrumental in securing the “Sadiq and Amin” verdict for Imran Khan from Chief Justice Saqib Nasir led Supreme Court is enough to depict the true picture of who controls the coercive machinery of the state behind closed doors.

Two political leaders, including Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif, are in particular suffering from megalomania. It is useless to expect that they will correct the inherently dysfunctional nature of our political system. We should expect even more melodrama from them. No serious plan. Anti-military posturing is their melodrama of choice; they don’t have any serious plan on how to manage the institution of the military, which has so clearly dominated the processes of governance in post-9/11 Pakistan. When it is the Army chief who is taking decisions about when to apply force and when to negotiate with terrorists, the only thing civilian leaders can really do is to engage in melodrama.