There is a story from the days of the British Raj about a certain Senior Civil Judge. Hearing allegations about this Judge’s corruption, his superior, an English Sessions Judge, confronted him and accused him of having taken the at-that-time-massive bribe of two hundred thousand rupees from a litigant. The Civil Judge, who hailed from a leading Sharraf family, was shocked and outraged. Drawing himself up to his full height, he boomed, “That’s an absolute lie. And an insult! I received five hundred thousand rupees, nothing less.”

Now the story is probably apocryphal, but there is no denying the ring of truth in it of a completely amoral perception of the privileges of power. Nor would it just have been about the native Indian employees of the Raj, posting to India being a well-recognised path to immense enrichment; one need only visit the resort town of Brighton in the south of England to see the grand – and sometimes ludicrously gaudy – bungalows built by officials of the Raj as their retirement homes. Go back further, to the days of the East India Company (the ‘Company Bahadur’), whose governors were routinely expected to enrich themselves at the expense of the natives. Robert Clive and Warren Hastings, the first two Governors-General, who attained epic heights of corruption, set the pace for those who were to follow them.

But, as Clive and Hastings may have pointed out, they were only following long established Indian traditions. Consider the custom of the Nazrana, the compulsory gift any litigant or favour seeker in Mughal times was required to place before the Kazi or other official before whom he was to appear. And the custom, perhaps, was a still older one, dating back maybe even to the days of Kautilya.

Now, before any of my readers think I am in any way attempting to “justify” corruption, let me clarify that this is not my intention. I merely wished to point out that, in our part of the world, corruption is as old as time itself and will not be easy to root out. It is, and has long been, an institutional kind of corruption, whose roots are shared up, down, and across the various channels of authority.

Consider all the businessmen who throng Islamabad, wining and dining and fawning over everyone from Section Officers to Federal Secretaries, to have Statutory Regulatory Orders (SROs) issued to favour their particular businesses – SROs that are often in complete contravention of Acts of Parliament or principles of natural justice. Consider the Customs Department, or the Income Tax people, or the Police, or the lower level courts of law, or the local Tehsildar. Consider the enormous well-fattened defence procurement contracts. I believe my point is clear. All these state functionaries, who control the actual levers of power, also have mechanisms for keeping those levers well greased. This is how the system works... and how it has worked since time immemorial.

But, of course, there is a new Johnny-come-lately, who has later entered the circle of corruption and is demanding his share: the politician.

Now, in the first few years of Pakistan’s independence, there were few major examples of corruption at the political level. Incompetence, yes, even outright stupidity, and petty misuse of power or privilege. But, although laws like PRODA and EBDO were directly targeted at them, few major scams featuring political figures surfaced during the 1950s and 1960s. It is probable that in Pakistan politicos were simply not important enough in the scheme of things.

This was not true of bureaucrats, however. In the successive attempts to “clean things up” by the Ayub, Yahya, and Bhutto governments, respectively 32, 303 and 1,100 officials were removed for corruption of one kind or another. Of course, nobody pretends that any of those sets of brooms swept completely clean. Nor, as I have suggested earlier in this piece, has bureaucratic corruption been either eliminated or abated.

While earlier political regimes had been simply too weak or unimportant to challenge their bureaucratic peers’ pocket-filling sprees, the Bhutto government was the first really effective political government in this country’s tragic history. Yet, surprisingly, there have been very few instances of the finger of corruption being credibly pointed at any important member of the federal government or parliament of those days. This is despite the best (or worst) efforts of the Zia dictatorship to discover the blots in the Bhutto copybook.

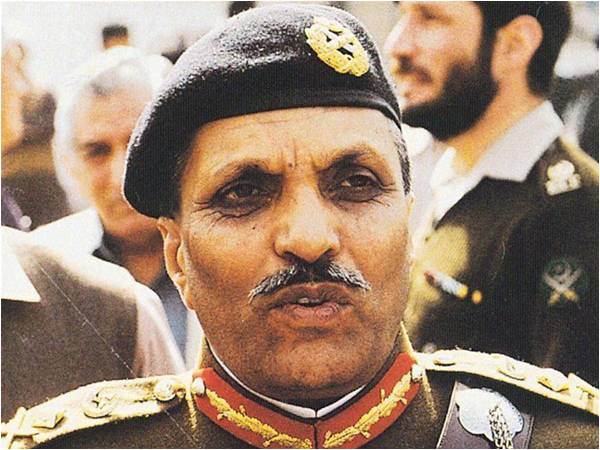

However, this cannot be said for the successor regime, that of the General with the comedian’s moustache and hooded executioner’s eyes. This is when political corruption struck deep roots and grew to a monstrous size. Look back at the history of those days and you may recall the regular ministerial changes that took place. It almost seemed as if Zia periodically permitted another and then another group to occupy office and enjoy the spoils thereof. And the spoils were plenty. On one side, American and Saudi aid was pouring in because of the war in Afghanistan and there were plenty of juicy commissions around for the sharing. On the other hand, were the enormous fortunes being made in the illegitimate weapons and drugs trades. One began to hear of numbered Swiss accounts and of generals and others who were reputed to be dollar billionaires.

After the Corruption Perceptions Index of Transparency International began to appear, the years 2004 to 2007, when Pervez Musharraf was in power, saw Pakistan lodged among the most corrupt 10 percent of the indexed countries. Since then, it has risen in the index and was near the top of the lower 30 percent of indexed countries in 2014.

This still suggests a sadly corrupt country. However, let us clearly understand that corruption, however reprehensible, is not the worst of political sins. Consider: nobody ever accused Hitler or Stalin of financial corruption. Need one say more?

The same Zia regime, which opened up the floodgates of political corruption in this country, also set in motion other even more deadly processes. Even today, twenty seven years after Zia was hurled in flames to the ground, the malignant processes he set in motion are still rotting the vitals of our state and society.

I thank my good friend Fakir Aijazuddin, who writes for another publication, for bringing to mind this quotation from Marcus Tullius Cicero, and trust he will not mind my using it again here:

“A nation can survive its fools, and even the ambitious. But it cannot survive treason from within. An enemy at the gates is less formidable, for he is known and carries his banner openly. But the traitor moves amongst those within the gate freely, his sly whispers rustling through all the alleys, heard in the very halls of government itself… He rots the soul of a nation… He infects the body politic so that it can no longer resist.”

Now the story is probably apocryphal, but there is no denying the ring of truth in it of a completely amoral perception of the privileges of power. Nor would it just have been about the native Indian employees of the Raj, posting to India being a well-recognised path to immense enrichment; one need only visit the resort town of Brighton in the south of England to see the grand – and sometimes ludicrously gaudy – bungalows built by officials of the Raj as their retirement homes. Go back further, to the days of the East India Company (the ‘Company Bahadur’), whose governors were routinely expected to enrich themselves at the expense of the natives. Robert Clive and Warren Hastings, the first two Governors-General, who attained epic heights of corruption, set the pace for those who were to follow them.

But, as Clive and Hastings may have pointed out, they were only following long established Indian traditions. Consider the custom of the Nazrana, the compulsory gift any litigant or favour seeker in Mughal times was required to place before the Kazi or other official before whom he was to appear. And the custom, perhaps, was a still older one, dating back maybe even to the days of Kautilya.

Now, before any of my readers think I am in any way attempting to “justify” corruption, let me clarify that this is not my intention. I merely wished to point out that, in our part of the world, corruption is as old as time itself and will not be easy to root out. It is, and has long been, an institutional kind of corruption, whose roots are shared up, down, and across the various channels of authority.

Nobody ever accused Hitler or Stalin of financial corruption

Consider all the businessmen who throng Islamabad, wining and dining and fawning over everyone from Section Officers to Federal Secretaries, to have Statutory Regulatory Orders (SROs) issued to favour their particular businesses – SROs that are often in complete contravention of Acts of Parliament or principles of natural justice. Consider the Customs Department, or the Income Tax people, or the Police, or the lower level courts of law, or the local Tehsildar. Consider the enormous well-fattened defence procurement contracts. I believe my point is clear. All these state functionaries, who control the actual levers of power, also have mechanisms for keeping those levers well greased. This is how the system works... and how it has worked since time immemorial.

But, of course, there is a new Johnny-come-lately, who has later entered the circle of corruption and is demanding his share: the politician.

Now, in the first few years of Pakistan’s independence, there were few major examples of corruption at the political level. Incompetence, yes, even outright stupidity, and petty misuse of power or privilege. But, although laws like PRODA and EBDO were directly targeted at them, few major scams featuring political figures surfaced during the 1950s and 1960s. It is probable that in Pakistan politicos were simply not important enough in the scheme of things.

This was not true of bureaucrats, however. In the successive attempts to “clean things up” by the Ayub, Yahya, and Bhutto governments, respectively 32, 303 and 1,100 officials were removed for corruption of one kind or another. Of course, nobody pretends that any of those sets of brooms swept completely clean. Nor, as I have suggested earlier in this piece, has bureaucratic corruption been either eliminated or abated.

While earlier political regimes had been simply too weak or unimportant to challenge their bureaucratic peers’ pocket-filling sprees, the Bhutto government was the first really effective political government in this country’s tragic history. Yet, surprisingly, there have been very few instances of the finger of corruption being credibly pointed at any important member of the federal government or parliament of those days. This is despite the best (or worst) efforts of the Zia dictatorship to discover the blots in the Bhutto copybook.

However, this cannot be said for the successor regime, that of the General with the comedian’s moustache and hooded executioner’s eyes. This is when political corruption struck deep roots and grew to a monstrous size. Look back at the history of those days and you may recall the regular ministerial changes that took place. It almost seemed as if Zia periodically permitted another and then another group to occupy office and enjoy the spoils thereof. And the spoils were plenty. On one side, American and Saudi aid was pouring in because of the war in Afghanistan and there were plenty of juicy commissions around for the sharing. On the other hand, were the enormous fortunes being made in the illegitimate weapons and drugs trades. One began to hear of numbered Swiss accounts and of generals and others who were reputed to be dollar billionaires.

After the Corruption Perceptions Index of Transparency International began to appear, the years 2004 to 2007, when Pervez Musharraf was in power, saw Pakistan lodged among the most corrupt 10 percent of the indexed countries. Since then, it has risen in the index and was near the top of the lower 30 percent of indexed countries in 2014.

This still suggests a sadly corrupt country. However, let us clearly understand that corruption, however reprehensible, is not the worst of political sins. Consider: nobody ever accused Hitler or Stalin of financial corruption. Need one say more?

The same Zia regime, which opened up the floodgates of political corruption in this country, also set in motion other even more deadly processes. Even today, twenty seven years after Zia was hurled in flames to the ground, the malignant processes he set in motion are still rotting the vitals of our state and society.

I thank my good friend Fakir Aijazuddin, who writes for another publication, for bringing to mind this quotation from Marcus Tullius Cicero, and trust he will not mind my using it again here:

“A nation can survive its fools, and even the ambitious. But it cannot survive treason from within. An enemy at the gates is less formidable, for he is known and carries his banner openly. But the traitor moves amongst those within the gate freely, his sly whispers rustling through all the alleys, heard in the very halls of government itself… He rots the soul of a nation… He infects the body politic so that it can no longer resist.”