The events of the first 3 weeks of the Trump Administration bring starkly to mind a story I have always remembered from my university days. In 1846, the great American naturalist, philosopher, poet, and moralist, Henry David Thoreau, spent a few days in jail (possibly as few as one) for refusing to pay taxes to a government that permitted slavery and was then waging a war he considered unjust against Mexico. While he was in jail, he was visited by his friend and intellectual rival, the transcendentalist poet, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said, “Henry, what are you doing in there?” Thoreau replied, “Waldo, what are you doing out there?”

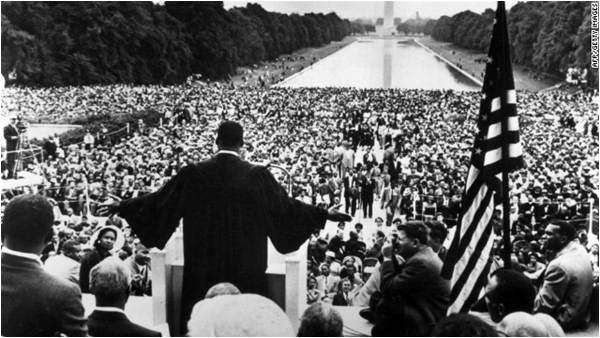

Whether this story is apocryphal I know not, but I treasure it because the point Thoreau was making has plagued citizens for many centuries: when must one take action rather than, by inaction, tacitly support the actions of a government that has lost its moral bearings, and its moral authority through immoral action? Thoreau’s political philosophy justified principled, non-violent resistance against governments that promulgate unjust laws or violate human rights, even if democratically elected, and even if the majority of the people supports such laws and violations. Because he argued that the majority was not always right, he was often accused of rejecting democracy, but he did not deny the general utility of majority rule. He asserted, however, that in exceptional cases the majority will support government’s violation of basic human rights, and that “conscientious objection” to such injustice is not only permissible but required in a democracy. As readers would suppose, Thoreau’s writings had great influence on the likes of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

Beneath Thoreau’s philosophic principle of conscientious objection lies a vast subjective terrain. Not everyone’s tripwire for conscientious objection is the same, and some have no tripwire at all. But for many Americans, perhaps an absolute majority, whatever shred of legitimate moral authority Trump had by being the duly elected President was lost after his first week in office. That week of controversial edicts culminated, as we all know, with an executive order entitled “Protecting the Nation from Terrorist Attacks by Foreign Nationals,” which ordered the suspension of visas to seven Muslim countries (Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen), a shut-down the US Refugee Program for 120 days, a reduction in the number of refugees admitted in 2017 to 50,000, an indefinite halt to Syrian refugee resettlement, and the introduction of a screening mechanism for the entry of foreign nationals.

This egregious act, offensive to possibly half the US population produced chaos at international airports in the US and abroad and provoked immediate protests at airports around the US. Thousands of lawyers came to major airports to offer pro-bono help to stranded immigrants (the US may have its own “lawyers movement”). It was immediately challenged in federal courts by several states and was stopped nationwide by a Seattle Federal Court on a challenge filed by the states of Minnesota and Washington. That decision was upheld by a higher Federal Appeals Court a few days later. As of the time this was being written, it was in limbo while the Trump administration decided what to do next; the option it seems likely to take is to rewrite the order to try to obviate the legal problems while accomplishing the same ends. Whether this is possible is open to question given the discriminatory ends it seeks, which is evidenced not by its own words as by the public words of Trump and his team about their long-term aim to ban Muslims from entering the country.

At this point, one could say that the US constitutional system of checks and balances is working as its authors intended. The third branch of government, the federal judiciary, has at least for the moment, checked the executive branch’s attempt to sideline constitutional protections in the name of security. The battle is not over; it has barely started. The challenged executive order could go to the Supreme Court as it is, or it could be displaced by a new order while, nonetheless, being tried on its substance in the Seattle court.

Conflicts between presidents and the federal courts have a long history in the US. In fact, they go back to 1803 in the celebrated Madison vs. Marbury case which was originally a suit against the executive branch by a citizen, but which Chief Justice Marshall used to establish the right of judicial review, which allows the Supreme Court to review laws and ordinances to determine if they are constitutional. Without Madison vs. Marbury, Trump’s ordinance would have faced no challenge as federal law gives the president very great power in national immigration policy.

In 1832, the concept of judicial review was severely tested when the same Chief Justice Marshall ruled that State of Georgia laws, aimed essentially at removing the Cherokee Indians from their lands, were unconstitutional. President Jackson, who supported Georgia in its aim to remove the Cherokees, was quoted as saying, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” He made no move to enforce it, and eventually, with Jackson’s help, the Cherokees were removed to Oklahoma. This is a very sad tale in itself, but the relevance of Jackson’s decision to ignore the decision is that it shows the flaw in relying on the system of judicial review as the main check on executive branch transgressions—the lack of an enforcement mechanism. The judicial branch depends on all parties recognizing and adhering to the rule of law.

And this is where Henry David Thoreau’s cry, “What are you doing out there, Waldo,” becomes pertinent and perhaps poignant. This is where the second branch of government, the Congress, comes in. It does have enforcement power, through legislation, or through impeachment. It is the Congress asserting its power that enabled Lincoln to shelve the right of habeas corpus for most of the civil war despite a decision from the Supreme Court that judged his action unconstitutional; it was the power of Congress to impeach that ultimately drove Richard Nixon, who was thinking of defying the federal courts, from the White House only 43 years ago.

The Congress is now controlled by the Republican Party, unlikely in most circumstances, to impeach a Republican president. There are many principled men and women on both sides of the aisle, but both sides seem blinded by a partisan fervour that seems to blot out any thought of the rule of law or national interest. In particular, the Republicans in Congress are intent on riding Trump’s coat tails while pushing their conservative agenda through Congress. I find it a distressing comment on our society to think that the tripwire for conscientious objection to flouting the rule of law, the foundational principle of American democracy, may have disappeared in the second branch of government due to partisan zeal.

That leaves just the states as the only institutional bulwark to injustice. The founders of this republic not only set up three branches of the federal government as checks and balances against each other, but they divided up authority between the federal government and the states. This means that states control police policies, health, safety, public morals, and the like. James Madison, one of the main authors of the constitution, wrote that the federal government should confine itself to “external objects, as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce”. Ironically, “states’ rights” was used by Southern states to justify slavery, and after the civil war, segregation. But now some Northern, Western, and Eastern states, not all by any means, are have turned “states’ rights” on its head, and are using it as the base of their conscientious objection to the Trump Administration’s illiberal policies.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

Whether this story is apocryphal I know not, but I treasure it because the point Thoreau was making has plagued citizens for many centuries: when must one take action rather than, by inaction, tacitly support the actions of a government that has lost its moral bearings, and its moral authority through immoral action? Thoreau’s political philosophy justified principled, non-violent resistance against governments that promulgate unjust laws or violate human rights, even if democratically elected, and even if the majority of the people supports such laws and violations. Because he argued that the majority was not always right, he was often accused of rejecting democracy, but he did not deny the general utility of majority rule. He asserted, however, that in exceptional cases the majority will support government’s violation of basic human rights, and that “conscientious objection” to such injustice is not only permissible but required in a democracy. As readers would suppose, Thoreau’s writings had great influence on the likes of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

When must one take action rather than, by inaction, tacitly support the actions of a government that has lost its moral bearings, and its moral authority through immoral action?

Beneath Thoreau’s philosophic principle of conscientious objection lies a vast subjective terrain. Not everyone’s tripwire for conscientious objection is the same, and some have no tripwire at all. But for many Americans, perhaps an absolute majority, whatever shred of legitimate moral authority Trump had by being the duly elected President was lost after his first week in office. That week of controversial edicts culminated, as we all know, with an executive order entitled “Protecting the Nation from Terrorist Attacks by Foreign Nationals,” which ordered the suspension of visas to seven Muslim countries (Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen), a shut-down the US Refugee Program for 120 days, a reduction in the number of refugees admitted in 2017 to 50,000, an indefinite halt to Syrian refugee resettlement, and the introduction of a screening mechanism for the entry of foreign nationals.

This egregious act, offensive to possibly half the US population produced chaos at international airports in the US and abroad and provoked immediate protests at airports around the US. Thousands of lawyers came to major airports to offer pro-bono help to stranded immigrants (the US may have its own “lawyers movement”). It was immediately challenged in federal courts by several states and was stopped nationwide by a Seattle Federal Court on a challenge filed by the states of Minnesota and Washington. That decision was upheld by a higher Federal Appeals Court a few days later. As of the time this was being written, it was in limbo while the Trump administration decided what to do next; the option it seems likely to take is to rewrite the order to try to obviate the legal problems while accomplishing the same ends. Whether this is possible is open to question given the discriminatory ends it seeks, which is evidenced not by its own words as by the public words of Trump and his team about their long-term aim to ban Muslims from entering the country.

At this point, one could say that the US constitutional system of checks and balances is working as its authors intended. The third branch of government, the federal judiciary, has at least for the moment, checked the executive branch’s attempt to sideline constitutional protections in the name of security. The battle is not over; it has barely started. The challenged executive order could go to the Supreme Court as it is, or it could be displaced by a new order while, nonetheless, being tried on its substance in the Seattle court.

Conflicts between presidents and the federal courts have a long history in the US. In fact, they go back to 1803 in the celebrated Madison vs. Marbury case which was originally a suit against the executive branch by a citizen, but which Chief Justice Marshall used to establish the right of judicial review, which allows the Supreme Court to review laws and ordinances to determine if they are constitutional. Without Madison vs. Marbury, Trump’s ordinance would have faced no challenge as federal law gives the president very great power in national immigration policy.

In 1832, the concept of judicial review was severely tested when the same Chief Justice Marshall ruled that State of Georgia laws, aimed essentially at removing the Cherokee Indians from their lands, were unconstitutional. President Jackson, who supported Georgia in its aim to remove the Cherokees, was quoted as saying, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” He made no move to enforce it, and eventually, with Jackson’s help, the Cherokees were removed to Oklahoma. This is a very sad tale in itself, but the relevance of Jackson’s decision to ignore the decision is that it shows the flaw in relying on the system of judicial review as the main check on executive branch transgressions—the lack of an enforcement mechanism. The judicial branch depends on all parties recognizing and adhering to the rule of law.

And this is where Henry David Thoreau’s cry, “What are you doing out there, Waldo,” becomes pertinent and perhaps poignant. This is where the second branch of government, the Congress, comes in. It does have enforcement power, through legislation, or through impeachment. It is the Congress asserting its power that enabled Lincoln to shelve the right of habeas corpus for most of the civil war despite a decision from the Supreme Court that judged his action unconstitutional; it was the power of Congress to impeach that ultimately drove Richard Nixon, who was thinking of defying the federal courts, from the White House only 43 years ago.

The Congress is now controlled by the Republican Party, unlikely in most circumstances, to impeach a Republican president. There are many principled men and women on both sides of the aisle, but both sides seem blinded by a partisan fervour that seems to blot out any thought of the rule of law or national interest. In particular, the Republicans in Congress are intent on riding Trump’s coat tails while pushing their conservative agenda through Congress. I find it a distressing comment on our society to think that the tripwire for conscientious objection to flouting the rule of law, the foundational principle of American democracy, may have disappeared in the second branch of government due to partisan zeal.

That leaves just the states as the only institutional bulwark to injustice. The founders of this republic not only set up three branches of the federal government as checks and balances against each other, but they divided up authority between the federal government and the states. This means that states control police policies, health, safety, public morals, and the like. James Madison, one of the main authors of the constitution, wrote that the federal government should confine itself to “external objects, as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce”. Ironically, “states’ rights” was used by Southern states to justify slavery, and after the civil war, segregation. But now some Northern, Western, and Eastern states, not all by any means, are have turned “states’ rights” on its head, and are using it as the base of their conscientious objection to the Trump Administration’s illiberal policies.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh