In a state like Pakistan, and more specifically in Pakhtunkhwa, where the scars of terrorism and violence run deep, we find ourselves in a tragic and terrible predicament. Between the chaos and turmoil of war, our thoughts and imaginations have suffered a profound loss. The very essence of creativity and artistic expression, so essential for our intellectual and emotional nourishment, seems to have decayed.

Wars, with their destructive force, indiscriminately claim not only lives and physical infrastructure but also the intangible treasures of culture and art. The toll of conflict on the human psyche is immeasurable, leaving scars that inhabit the cultivation of literature, poetry and other forms of artistic expression. In the face of violence, our ability to imagine, to create and to engage with the world through the lens of art becomes stifled, overshadowed by the pressing realities of survival and restoration.

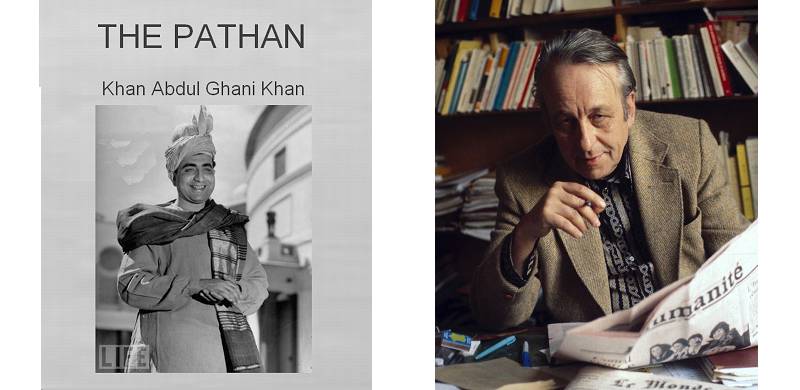

Yet, in acknowledging this loss, and as a hopeless pessimist, still I think that to unlock the potential for social change, one must embrace the inherent absurdity of their surroundings and strive to regain the most precious lost gift; of thought and of imagination. With almost nothing in my hands, I with some of my friends took the initiative to form a literary circle within our department—Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Peshawar. In this literary circle, we formed a Reading Club where collectively we select a book and read it within two weeks, and on every second Monday we gather and discuss it. The book we selected for last Monday was Ghani Khan’s The Pathan, which was first published in 1947 and ironically is less known in academic and intellectual circles.

Written during his time as a young student at Edwards College, Ghani Khan, poet, philosopher, sculptor and son of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (who was lovingly known as Bacha Khan), offers profound insights into societal customs and their enduring influence on the Pashtuns’ life. One of the most interesting aspects of our discussion was the exploration of customs: how laws ingrained in a race become customs, persisting long after their original purpose has faded from memory. It is through these customs that individuals pass down not only physical traits but also their fears, songs, and beliefs. As Ghani Khan writes: “When a law is bred into the very fiber of a race it becomes a custom and persists long after the need is gone and the occasion forgotten. For man gives to his children not only the shape of his own nose and the cranks in his character, he also teaches them his fears and forebodings, his songs and curses. He molds his child as nearly as he can to his own shape” adding: “The civilised man does it through his schools and books, the press and platform. He is not ashamed to use a little gunpowder and occasionally the hanging block to drive home some of his points.’’

Here one of the discussants drew our attention to the remarkable resonance between Ghani Khan’s insights and the work of French philosopher Louis Althusser.

Althusser (1918-1990) is known for his influential essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” (1969), in which he shed light on the multifaceted mechanisms through which societies are governed and ideologies are disseminated. What fascinated us, even more, was the fact that Ghani Khan wrote his analysis decades before Althusser, which I think here needs a little bit of commentary.

Ghani Khan’s observation about laws becoming customs reflects the idea that customs, like laws, shape the behaviour and beliefs of individuals. “The civilised man does it through his schools and books, the press and platform,” Ghani Khan points out. Althusser’s concept of ISAs (Ideological State Apparatuses) includes institutions such as Churches, Parties, Trade Unions, families, schools, newspapers, etc that disseminate dominant ideologies and values and pass them on to the younger generation. Furthermore, Ghani Khan’s mention of “using gunpowder and the hanging block to enforce certain points” signifies the exercise of power and control. Althusser’s concept of the repressive state apparatus (RSA) functions massively and predominantly by repression (including physical repression), while functioning secondarily by ideology and represents the coercive apparatuses employed by the State to maintain social order and suppress dissent.

Both Ghani Khan and Althusser’s theories highlight the interplay between customs, laws, institutions, and power dynamics in shaping societal norms and maintaining the existing social order. They both highlight how the transmission of ideas and values occurs through both peaceful means, like education and coercive measures when necessary.

Addressing the British colonialists, Ghani Khan further writes: ‘‘Your laws are as stupid to him as his customs are to you.’’ In a daring style here, Ghani Khan adopts a totally postmodern lens, boldly asserting that the laws cherished by one group are just as foolish to another as the other’s customs are to them. Here, he challenges the notion of absolute truth and mocks the idea of fixed, universal standards. With a touch of irony, Ghani Khan exposes the inherent subjectivity of human experiences, where each individual or community creates their own intricate web of meaning.

In drawing a comparison between Ghani Khan and Althusser, it is important to make clear that the intention is not to discredit one in favour of the other or engage in a competition of ideas. Rather, the aim of writing this exploration, the resonance between Ghani Khan’s insights and Althusser’s work, is simply to shed light on the significance of our own literature, which has often been marginalised by the policies of the State.

Alongside questioning state policies and attitude towards local literature, it also highlights the need for our scholars and intellectuals to give a little of their valuable attention to our rich literary heritage and place a little emphasis on its study too, if possible. We must pay attention to the timeless wisdom and universal themes embedded within our own literature, which not only deepen our understanding of Pashtun culture and the misrepresentation by others, but also contribute valuable perspectives and insights to the global intellectual discourse.

Our literature holds the power to transcend cultural boundaries and offer unique perspectives on the human condition. Through such exploration and appreciation of our own literary gems, we can form our own narrative and can proudly share our intellectual heritage with the world.

Wars, with their destructive force, indiscriminately claim not only lives and physical infrastructure but also the intangible treasures of culture and art. The toll of conflict on the human psyche is immeasurable, leaving scars that inhabit the cultivation of literature, poetry and other forms of artistic expression. In the face of violence, our ability to imagine, to create and to engage with the world through the lens of art becomes stifled, overshadowed by the pressing realities of survival and restoration.

Yet, in acknowledging this loss, and as a hopeless pessimist, still I think that to unlock the potential for social change, one must embrace the inherent absurdity of their surroundings and strive to regain the most precious lost gift; of thought and of imagination. With almost nothing in my hands, I with some of my friends took the initiative to form a literary circle within our department—Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Peshawar. In this literary circle, we formed a Reading Club where collectively we select a book and read it within two weeks, and on every second Monday we gather and discuss it. The book we selected for last Monday was Ghani Khan’s The Pathan, which was first published in 1947 and ironically is less known in academic and intellectual circles.

Written during his time as a young student at Edwards College, Ghani Khan, poet, philosopher, sculptor and son of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (who was lovingly known as Bacha Khan), offers profound insights into societal customs and their enduring influence on the Pashtuns’ life. One of the most interesting aspects of our discussion was the exploration of customs: how laws ingrained in a race become customs, persisting long after their original purpose has faded from memory. It is through these customs that individuals pass down not only physical traits but also their fears, songs, and beliefs. As Ghani Khan writes: “When a law is bred into the very fiber of a race it becomes a custom and persists long after the need is gone and the occasion forgotten. For man gives to his children not only the shape of his own nose and the cranks in his character, he also teaches them his fears and forebodings, his songs and curses. He molds his child as nearly as he can to his own shape” adding: “The civilised man does it through his schools and books, the press and platform. He is not ashamed to use a little gunpowder and occasionally the hanging block to drive home some of his points.’’

Here one of the discussants drew our attention to the remarkable resonance between Ghani Khan’s insights and the work of French philosopher Louis Althusser.

Althusser (1918-1990) is known for his influential essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” (1969), in which he shed light on the multifaceted mechanisms through which societies are governed and ideologies are disseminated. What fascinated us, even more, was the fact that Ghani Khan wrote his analysis decades before Althusser, which I think here needs a little bit of commentary.

Ghani Khan’s observation about laws becoming customs reflects the idea that customs, like laws, shape the behaviour and beliefs of individuals. “The civilised man does it through his schools and books, the press and platform,” Ghani Khan points out. Althusser’s concept of ISAs (Ideological State Apparatuses) includes institutions such as Churches, Parties, Trade Unions, families, schools, newspapers, etc that disseminate dominant ideologies and values and pass them on to the younger generation. Furthermore, Ghani Khan’s mention of “using gunpowder and the hanging block to enforce certain points” signifies the exercise of power and control. Althusser’s concept of the repressive state apparatus (RSA) functions massively and predominantly by repression (including physical repression), while functioning secondarily by ideology and represents the coercive apparatuses employed by the State to maintain social order and suppress dissent.

Both Ghani Khan and Althusser’s theories highlight the interplay between customs, laws, institutions, and power dynamics in shaping societal norms and maintaining the existing social order. They both highlight how the transmission of ideas and values occurs through both peaceful means, like education and coercive measures when necessary.

Addressing the British colonialists, Ghani Khan further writes: ‘‘Your laws are as stupid to him as his customs are to you.’’ In a daring style here, Ghani Khan adopts a totally postmodern lens, boldly asserting that the laws cherished by one group are just as foolish to another as the other’s customs are to them. Here, he challenges the notion of absolute truth and mocks the idea of fixed, universal standards. With a touch of irony, Ghani Khan exposes the inherent subjectivity of human experiences, where each individual or community creates their own intricate web of meaning.

In drawing a comparison between Ghani Khan and Althusser, it is important to make clear that the intention is not to discredit one in favour of the other or engage in a competition of ideas. Rather, the aim of writing this exploration, the resonance between Ghani Khan’s insights and Althusser’s work, is simply to shed light on the significance of our own literature, which has often been marginalised by the policies of the State.

Alongside questioning state policies and attitude towards local literature, it also highlights the need for our scholars and intellectuals to give a little of their valuable attention to our rich literary heritage and place a little emphasis on its study too, if possible. We must pay attention to the timeless wisdom and universal themes embedded within our own literature, which not only deepen our understanding of Pashtun culture and the misrepresentation by others, but also contribute valuable perspectives and insights to the global intellectual discourse.

Our literature holds the power to transcend cultural boundaries and offer unique perspectives on the human condition. Through such exploration and appreciation of our own literary gems, we can form our own narrative and can proudly share our intellectual heritage with the world.