The first time I remember being called camp was in the seconds before the curtains opened on my 9th grade school play. A friendly teacher had said it – in a tone of bemused admiration I like to think – and although I didn’t know what it meant, I had an inkling. I was an effeminate, overweight, visually extravagant but athletically demure child. These were not always easy things to be in an all-boys school although it didn’t occur to me to mind. I had a strong group of friends, a loving family and a talent to weaponize words. You had to, especially if you were dressed as a witch, as I was.

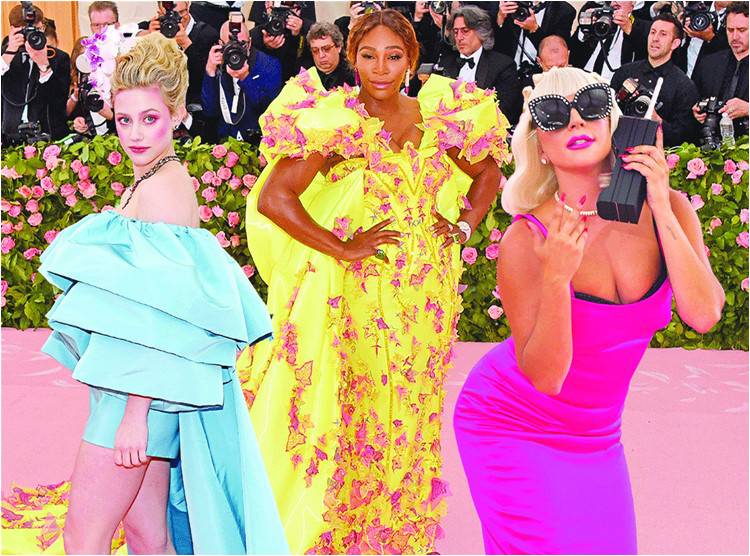

I was thinking about these things and more when I went to see the Costume Institute’s show at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The exhibitions opens every year with a storied Met Gala, where the worlds stars converge in a parade of couture exemplifying that year’s themes. The theme this year was Camp, as defined by Susan Sontag’s essay “Notes on Camp” and it tried to draw a line connecting the notion of camp to (exclusively white) cultural moments in history.

The show is divided into three parts. The first is a sort of truncated introduction to the idea of camp, and places objects from the museum’s collection along with historical costume pieces as a sort of quick overview of camp from Versailles through Oscar Wilde. Its by far the most successful part of the exhibition primarily because its the only one that capitulates to the idea that Camp can manifest in any part of culture. To prove this the show gives you a richly textured menagerie of diaries, statues, garments, portraits, book covers and drawings that, once triangulated, provide us some kind of definition of the term.

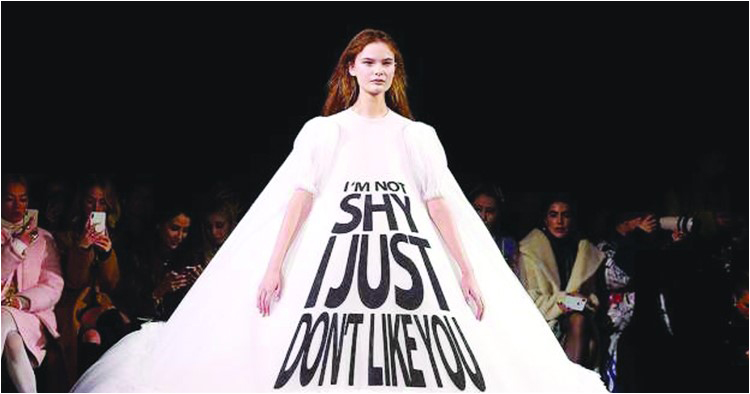

The second section is an homage to the more than 50 definitions that Susan Sontag came up with in her essay. In many cases they represent or are the actual objects that Sontag mentions in her essay (she lived in New York and frequented the museum), like the Caravaggio painting of the musicians or else a later 19th century dinner jacket ensemble. It’s fun, but any kind of intellectual momentum dissipates in the third room, where display boxes of couture creations are stacked like matchboxes on top of each other. Occasionally the voice of Judy Garlands singing “Over the Rainbow” wades out through the air, but otherwise you are left to consider clothes with little other context. Some of them were on the runways as recently as January, while others were from several decades ago. Most were boring.

As I hate-walked through the remaining exhibit, I kept thinking about that first room – the one with the statues – because it made apparent that Camp doesn’t just mean glorifying extravagance for the sake of it. Quite the opposite: camp usually comes from people without power, and embedded in their glorification of things like Rococco royalty or the excess of sequined showmanship, is that in appropriating the trappings of power they are also acknowledging the power that is so often denied by the world. Marlene Dietrich wore men’s suits, and that was camp, but it was camp not just because of the idea of cross-dressing, but because of the power dynamics that a woman wearing a man’s clothes in the 1930s disrupted.

When the disenfranchised create their own culture as both a reaction to and critique of mainstream power dynamics, we often get interesting art. But that didn’t happen at this Met show. The last room, with its dozens of Instagram-worthy clothes, made no effort to diversify its approach to anything beyond Uber-luxe Euro couture. There was no reference to the other temples of Camp, like ballet, opera or the theatre. No reference to Hollywood movies or Broadway shows; no Streisand, Cher, Midler or Madonna. There was little representation of African American history of camp, of Dorothy Dandridge or Ertha Kitt. There was no superheroes like Catwoman from comic books, and perhaps most shocking of all, there was nothing outside of a starkly white narrative. No mention of Bollywood, or Latin American cinema, or African prints or Chinese silks. The whole thing reeked of the worst kind of privileged, self-referential elitism. At the end, it felt like they’d missed the whole point of Camp as an idea that gives strength to those who need it most.

“Was that even Camp?” A friend asked me as we left the museum and I thought back to my school play.

My face was in dark, gothic makeup and I was pacing backstage so that the floor-length hooded can ballooned around me. The role had been a goal of mine since I had seen the movie The Craft the year before, and become briefly but powerfully obsessed with Wicca. My long black painted nails gripping the sweeper’s wooden broom nervously right before I was about to hunch on stage as Witch 1 in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

“You look so Camp!” she had said before moving onto sewing another boy into his costume, and right then I had that momentary panic when you show a bit of your true self and fear you’ve shown too much. Any fat effeminate boy knows the feeling because its always there – the feeling that power might be taken from you at any moment because you don’t control it. Just then my spotlight came on and I swooped on stage magnificently. Why? Because that short, fat, effeminate boy imagining himself as a potent witch made him feel powerful and glorious. That is camp. And thank God for it.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

I was thinking about these things and more when I went to see the Costume Institute’s show at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The exhibitions opens every year with a storied Met Gala, where the worlds stars converge in a parade of couture exemplifying that year’s themes. The theme this year was Camp, as defined by Susan Sontag’s essay “Notes on Camp” and it tried to draw a line connecting the notion of camp to (exclusively white) cultural moments in history.

The show is divided into three parts. The first is a sort of truncated introduction to the idea of camp, and places objects from the museum’s collection along with historical costume pieces as a sort of quick overview of camp from Versailles through Oscar Wilde. Its by far the most successful part of the exhibition primarily because its the only one that capitulates to the idea that Camp can manifest in any part of culture. To prove this the show gives you a richly textured menagerie of diaries, statues, garments, portraits, book covers and drawings that, once triangulated, provide us some kind of definition of the term.

The second section is an homage to the more than 50 definitions that Susan Sontag came up with in her essay. In many cases they represent or are the actual objects that Sontag mentions in her essay (she lived in New York and frequented the museum), like the Caravaggio painting of the musicians or else a later 19th century dinner jacket ensemble. It’s fun, but any kind of intellectual momentum dissipates in the third room, where display boxes of couture creations are stacked like matchboxes on top of each other. Occasionally the voice of Judy Garlands singing “Over the Rainbow” wades out through the air, but otherwise you are left to consider clothes with little other context. Some of them were on the runways as recently as January, while others were from several decades ago. Most were boring.

When the disenfranchised create their own culture as both a reaction to and critique of mainstream power dynamics, we often get interesting art. But that didn’t happen at this Met show

As I hate-walked through the remaining exhibit, I kept thinking about that first room – the one with the statues – because it made apparent that Camp doesn’t just mean glorifying extravagance for the sake of it. Quite the opposite: camp usually comes from people without power, and embedded in their glorification of things like Rococco royalty or the excess of sequined showmanship, is that in appropriating the trappings of power they are also acknowledging the power that is so often denied by the world. Marlene Dietrich wore men’s suits, and that was camp, but it was camp not just because of the idea of cross-dressing, but because of the power dynamics that a woman wearing a man’s clothes in the 1930s disrupted.

When the disenfranchised create their own culture as both a reaction to and critique of mainstream power dynamics, we often get interesting art. But that didn’t happen at this Met show. The last room, with its dozens of Instagram-worthy clothes, made no effort to diversify its approach to anything beyond Uber-luxe Euro couture. There was no reference to the other temples of Camp, like ballet, opera or the theatre. No reference to Hollywood movies or Broadway shows; no Streisand, Cher, Midler or Madonna. There was little representation of African American history of camp, of Dorothy Dandridge or Ertha Kitt. There was no superheroes like Catwoman from comic books, and perhaps most shocking of all, there was nothing outside of a starkly white narrative. No mention of Bollywood, or Latin American cinema, or African prints or Chinese silks. The whole thing reeked of the worst kind of privileged, self-referential elitism. At the end, it felt like they’d missed the whole point of Camp as an idea that gives strength to those who need it most.

“Was that even Camp?” A friend asked me as we left the museum and I thought back to my school play.

My face was in dark, gothic makeup and I was pacing backstage so that the floor-length hooded can ballooned around me. The role had been a goal of mine since I had seen the movie The Craft the year before, and become briefly but powerfully obsessed with Wicca. My long black painted nails gripping the sweeper’s wooden broom nervously right before I was about to hunch on stage as Witch 1 in Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

“You look so Camp!” she had said before moving onto sewing another boy into his costume, and right then I had that momentary panic when you show a bit of your true self and fear you’ve shown too much. Any fat effeminate boy knows the feeling because its always there – the feeling that power might be taken from you at any moment because you don’t control it. Just then my spotlight came on and I swooped on stage magnificently. Why? Because that short, fat, effeminate boy imagining himself as a potent witch made him feel powerful and glorious. That is camp. And thank God for it.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com