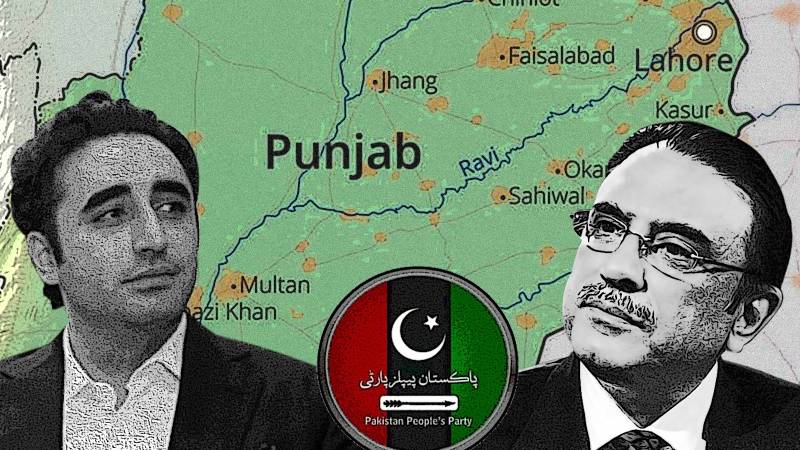

It can be argued that the real winner of the February 8th election is the PPP. The party has retained its stronghold in Sindh, made significant inroads in Balochistan and secured the Presidency for Asif Ali Zardari, all while avoiding the burden of the federal government. Yet despite a favourable election result, how much closer is the People’s Party to its ultimate objective of making Bilawal Bhutto the Prime Minister with a simple majority? Unfortunately for the PPP, not much, and the key factor behind this is the party’s position in the Punjab.

The party managed a meagre 7 seats in the National Assembly from the Punjab, and 10 seats in the Punjab provincial assembly. If we delve into the details of the results and compare them to previous elections, the severity of the situation becomes even clearer – particularly in central and northern Punjab. Take Attock district as an example - in the 2008 election, Sardar Saleem Haider of the PPP won a National Assembly seat with a lead of approximately 13,000 votes – in every election since (2013, 2018 and 2024), the PPP candidate has finished fourth. The same pattern can be seen in multiple districts across the province. Even Bilawal’s own decision to contest a National Assembly seat from Lahore, although a brave one, did not yield the results the party would have wanted with Bilawal losing the seat by a sizeable margin.

Although the PPP took some important initiatives for the democratic system such as the 18th Amendment, the party’s 2008-2013 tenure is mostly associated with rampant loadshedding and numerous corruption allegations against key leaders.

The desperate state of the party in the Punjab is a far cry from the 1970s, or even the late 1990s when a PPP ticket was enough to ensure a candidate’s victory in the province. It is worth mentioning that multiple old-school heavyweights from the Punjab including Sadiq Hussain Qureshi, Ghulam Mustafa Khar and Balakh Sher Mazari were all part of the PPP at some stage in their political career – such was the party’s appeal in the Punjab. If you had said to these gentlemen that Benazir’s son will contest a National Assembly seat from Lahore and finish third, they would have had a good laugh.

I recently spoke with a long-time PPP supporter based in Lahore who recalled with nostalgia the 1988 election – he narrated, with a mix of laughter and emotion, how him and his friends would drive through the streets of Lahore with PPP flags on their cars. This was the first election his generation experienced after a 10-year dictatorship – the PPP was the flag-bearer of democracy in the country and the people rallied with passion and zeal behind Bhutto’s daughter. Bhuttoism was at its peak and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s ultimate sacrifice coupled with the intense support of the party amongst the working class resulted in Benazir becoming the first female Prime Minister of a Muslim majority country.

What went so horribly wrong? It is difficult to pinpoint one reason and there is almost certainly a mix of factors that have contributed to this mind-boggling downfall. To begin with, although the PPP took some important initiatives for the democratic system such as the 18th Amendment, the party’s 2008-2013 tenure is mostly associated with rampant loadshedding and numerous corruption allegations against key leaders.

Karachi’s dilapidated infrastructure and underdevelopment in Sindh’s rural districts have further eroded the party’s support base in the Punjab. Contrary to popular belief, the PPP has done some impactful work in Sindh, particularly in the healthcare space – an example is the expansion of the National Institute of Cardiovascular Disease (NICVD). However, it is nowhere near the level of work that should have been done considering the PPP has had the Sindh government for nearly two decades now.

The vast majority of young voters have never really considered the PPP as a serious alternative, not necessarily because they agree or disagree with the PPP’s policies, but because the party is so far removed from the political discourse in the province.

Lack of leadership cannot be ruled out either - Bilawal has only recently taken the reins and the fact is that many of the PPP’s current central and provincial leaders were in charge back in 2008 and it is under their watch that the PPP went from 82 Punjab Assembly seats in 2008 to 10 seats in 2024.

Perhaps the most worrying factor for the PPP is the disconnect between the party and young voters in the Punjab. According to data published by the ECP, the proportion of young voters (18-35) is approximately 42% in the province – many of these voters were born two or three years prior to Benazir’s assassination and by the time they entered their teens, it was 2018 or 2019, by which time the PPP’s support base had already declined significantly in the Punjab. The vast majority of young voters have never really considered the PPP as a serious alternative, not necessarily because they agree or disagree with the PPP’s policies, but because the party is so far removed from the political discourse in the province.

What does all this mean then for the party going forward? Is it all over for the PPP in the Punjab? Not just yet – as the newly-elected President Asif Ali Zardari correctly remarked in an interview prior to the elections: “the PPP is still alive in every village in the Punjab.” This is true – PPP loyalists, or ‘jiyalas’ still exist in nearly every union council across the province, but the number is shrinking at an alarming rate.

The PPP must, as a priority, chalk out and implement a detailed strategy of mobilizing the party in every district across the Punjab, and more importantly develop a narrative that will appeal to voters in the province - gone are the days when the party could rely on the Bhutto legacy for votes. The PPP hasn’t fallen off the cliff just yet as far as the Punjab is concerned, but it is standing right at the edge.