The events which followed the death of the sixth great Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, are well known. Every high school graduate in Pakistan has read about them, memorised them, and eventually forgotten them.

William Dalrymple brings them to life with his vivid narration. Readers feel as if they are witnessing the tumultuous events unfold in real time. His book stands in contrast to most history books, which are so dreary that readers begin to skip pages and some doze off.

Anarchy is written for the general reader and assumes no prior knowledge of Indian history. Yet it is based on a meticulous reading of the vast literature on the topic, and his distillation of insights from several primary sources.

Of the 522 pages in the book, 94 document the sources. There are a few shortcomings. What is missing is a table that documents the timelines of the major events described in the book and maps of the major battles. On several pages, dates are mentioned without citing the months or the years.

The Mughals had ruled India for two centuries. Babur, a man from Central Asia, who traced his lineage from Timur and Chinggis Khan, founded the Mughal Empire in 1526, after defeating Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi at the Battle of Panipat. In 1600, his grandson Akbar successfully integrated the diverse cultures of India and restored harmony to Hindu-Muslim relations. His grandson Aurangzeb did the opposite. He executed his elder brother, Dara Shukoh, who Shah Jahan, his father, had appointed emperor when he fell ill. Aurangzeb foisted himself on the throne and went so far as to imprison Shah Jahan once his health had been restored.

Aurangzeb, a puritanical Muslim, extended the empire to its maximum territorial extent in his zeal to place all of India under Islamic rule. He was intolerant of dissent, an absolutist. But the Marathas remained a thorn in his side. His prolonged battles with them eventually drained the Mughal treasury.

India was in the grip of famine and bubonic plague by the time death knocked on the door. Nearly 90 years old, lying on his deathbed, he confessed to his son, “I came alone and I go as a stranger. I do not know who I am, nor what I have been doing.”

He did not have a clearly defined succession plan. After his death, in-fighting broke out among his three sons. The empire essentially died with him, 200 years after it was established.

It was just a question of time before foreign rulers would sense its vulnerability. The first man to do so was Nader Shah, who had seized the Persian throne in 1732, ending 200 years of Safavid rule. He invaded Afghanistan on 21 May 1739. The Mughals in Kabul surrendered in just over a month. In less than three months, Nader Shah was at Karnal, one hundred miles north of Delhi. He defeated a Mughal force of nearly a million men, half of whom were fighters. Soon thereafter, he was knocking on the gates of Delhi.

He captured the Mughal emperor, who had an army of a million “bold and well-equipped horsemen” under his command. Delhi was raped and pillaged like never before. More than 100,000 were killed in this Muslim-against-Muslim battle. A pyramids of skulls was constructed so that his name would never be forgotten.

Nader Shah had no intention of ruling India. He had come simply to gather treasure to fight his real enemies, the Ottomans and the Russians. When he left Delhi, he took treasures amounting to $10 billion in today’s currency, validating the dictum “to the victor belong the spoils of war.” Among them was the coveted Peacock Throne of Emperor Jahangir. In it was embedded the Kohinoor Diamond, the Timur ruby and many other precious jewels.

India’s travails had just begun. It would be attacked no less than 17 times by another Muslim sovereign. This time the invader would be the Afghan monarch Ahmad Shah Durrani, whose first arrival in Delhi was in 1757. He secured his biggest win in 1761 at the Battle of Panipat (where Babur had defeated Lodhi in 1526) against the Marathas. Thousands of them were killed; more than 40,000 were captured, disarmed and put to the sword. The Afghans would rule Delhi for another nine years.

Along the way, the Rohilla Afghans captured and blinded the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam. Even when blinded, the powerless emperor did not suffer from a shortage of titles. He was “His Sacred Majesty, the Shadow of God, Vice-Regent of the All-Merciful, King of the World, Exalted Seed, the Emperor who is a Refuge to the World.”

The period that followed the demise of the Mughal Empire was one of anarchy, followed eventually by the imposition of law and order. Nature abhors a vacuum. The only question was as to who would fill it.

That role went to an obscure foreign entity, the East India Company (“Company”). It was a publicly traded company formed to trade in the “East Indies,” i.e., the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia, and later with East Asia.

The same company had played a part in triggering the American Revolution in the late 1700s. The Boston Tea Party was provoked “by fears that the Company might now be let loose on the thirteen colonies, much as it had been in Bengal.”

It would take the Company several decades to seize control of India, which it did would do through a series of battles. By 1803, in the short span of 50 years, the Company “had captured the Mughal capital of Delhi, and within it, the sightless monarch, Shah Alam, sitting blinded in his ruined palace, the Company had trained up a private security force of around 200,000 – twice the size of the British army – and marshalled more firepower than any nation state in Asia.

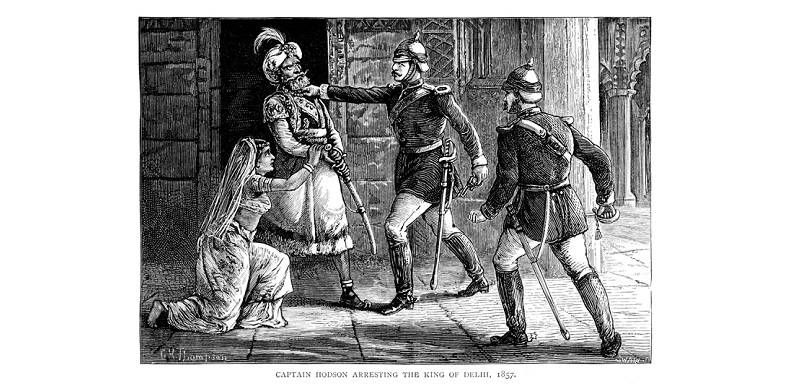

For half a century, it would govern India, with a Mughal “puppet” Emperor at the helm. Its downfall would be triggered by the Great Uprising in 1857, during Bahadur Shah Zafar’s reign. The emperor would pay a price for approving the uprising. The British would take him in shackles in a bullock cart to Burma where he would be imprisoned and eventually die. It was his fate to be buried anonymously.

A year later, the British Empire would replace the Company as India’s undisputed ruler. Henceforth, for the next 90 years, India would be governed by the Viceroys. During the British Raj, India would be lauded as the jewel in Britain’s crown.

William Dalrymple brings them to life with his vivid narration. Readers feel as if they are witnessing the tumultuous events unfold in real time. His book stands in contrast to most history books, which are so dreary that readers begin to skip pages and some doze off.

Anarchy is written for the general reader and assumes no prior knowledge of Indian history. Yet it is based on a meticulous reading of the vast literature on the topic, and his distillation of insights from several primary sources.

Of the 522 pages in the book, 94 document the sources. There are a few shortcomings. What is missing is a table that documents the timelines of the major events described in the book and maps of the major battles. On several pages, dates are mentioned without citing the months or the years.

The Mughals had ruled India for two centuries. Babur, a man from Central Asia, who traced his lineage from Timur and Chinggis Khan, founded the Mughal Empire in 1526, after defeating Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi at the Battle of Panipat. In 1600, his grandson Akbar successfully integrated the diverse cultures of India and restored harmony to Hindu-Muslim relations. His grandson Aurangzeb did the opposite. He executed his elder brother, Dara Shukoh, who Shah Jahan, his father, had appointed emperor when he fell ill. Aurangzeb foisted himself on the throne and went so far as to imprison Shah Jahan once his health had been restored.

Aurangzeb, a puritanical Muslim, extended the empire to its maximum territorial extent in his zeal to place all of India under Islamic rule. He was intolerant of dissent, an absolutist. But the Marathas remained a thorn in his side. His prolonged battles with them eventually drained the Mughal treasury.

India was in the grip of famine and bubonic plague by the time death knocked on the door. Nearly 90 years old, lying on his deathbed, he confessed to his son, “I came alone and I go as a stranger. I do not know who I am, nor what I have been doing.”

He did not have a clearly defined succession plan. After his death, in-fighting broke out among his three sons. The empire essentially died with him, 200 years after it was established.

It was just a question of time before foreign rulers would sense its vulnerability. The first man to do so was Nader Shah, who had seized the Persian throne in 1732, ending 200 years of Safavid rule. He invaded Afghanistan on 21 May 1739. The Mughals in Kabul surrendered in just over a month. In less than three months, Nader Shah was at Karnal, one hundred miles north of Delhi. He defeated a Mughal force of nearly a million men, half of whom were fighters. Soon thereafter, he was knocking on the gates of Delhi.

Even when blinded, the powerless emperor did not suffer from a shortage of titles. He was “His Sacred Majesty, the Shadow of God, Vice-Regent of the All-Merciful, King of the World, Exalted Seed, the Emperor who is a Refuge to the World”

He captured the Mughal emperor, who had an army of a million “bold and well-equipped horsemen” under his command. Delhi was raped and pillaged like never before. More than 100,000 were killed in this Muslim-against-Muslim battle. A pyramids of skulls was constructed so that his name would never be forgotten.

Nader Shah had no intention of ruling India. He had come simply to gather treasure to fight his real enemies, the Ottomans and the Russians. When he left Delhi, he took treasures amounting to $10 billion in today’s currency, validating the dictum “to the victor belong the spoils of war.” Among them was the coveted Peacock Throne of Emperor Jahangir. In it was embedded the Kohinoor Diamond, the Timur ruby and many other precious jewels.

India’s travails had just begun. It would be attacked no less than 17 times by another Muslim sovereign. This time the invader would be the Afghan monarch Ahmad Shah Durrani, whose first arrival in Delhi was in 1757. He secured his biggest win in 1761 at the Battle of Panipat (where Babur had defeated Lodhi in 1526) against the Marathas. Thousands of them were killed; more than 40,000 were captured, disarmed and put to the sword. The Afghans would rule Delhi for another nine years.

Along the way, the Rohilla Afghans captured and blinded the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam. Even when blinded, the powerless emperor did not suffer from a shortage of titles. He was “His Sacred Majesty, the Shadow of God, Vice-Regent of the All-Merciful, King of the World, Exalted Seed, the Emperor who is a Refuge to the World.”

The period that followed the demise of the Mughal Empire was one of anarchy, followed eventually by the imposition of law and order. Nature abhors a vacuum. The only question was as to who would fill it.

That role went to an obscure foreign entity, the East India Company (“Company”). It was a publicly traded company formed to trade in the “East Indies,” i.e., the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia, and later with East Asia.

The same company had played a part in triggering the American Revolution in the late 1700s. The Boston Tea Party was provoked “by fears that the Company might now be let loose on the thirteen colonies, much as it had been in Bengal.”

It would take the Company several decades to seize control of India, which it did would do through a series of battles. By 1803, in the short span of 50 years, the Company “had captured the Mughal capital of Delhi, and within it, the sightless monarch, Shah Alam, sitting blinded in his ruined palace, the Company had trained up a private security force of around 200,000 – twice the size of the British army – and marshalled more firepower than any nation state in Asia.

For half a century, it would govern India, with a Mughal “puppet” Emperor at the helm. Its downfall would be triggered by the Great Uprising in 1857, during Bahadur Shah Zafar’s reign. The emperor would pay a price for approving the uprising. The British would take him in shackles in a bullock cart to Burma where he would be imprisoned and eventually die. It was his fate to be buried anonymously.

A year later, the British Empire would replace the Company as India’s undisputed ruler. Henceforth, for the next 90 years, India would be governed by the Viceroys. During the British Raj, India would be lauded as the jewel in Britain’s crown.