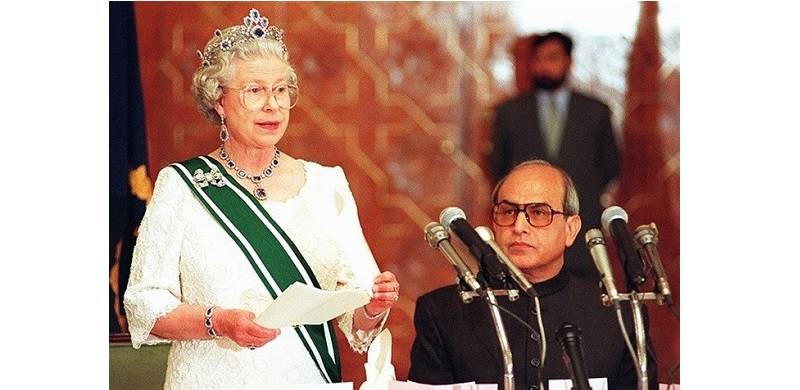

The death of Queen Elizabeth II has been marked nearly universally as the passing away of a lady of immense grace and dignity, whose seventy-year reign will be remembered for her devotion to duty.

For many Pakistanis with an interest in our nation’s history, there is an added sense of remembrance. From 1947-1956, Pakistan had dominion status and it functioned as a constitutional monarchy. For four of those years, from 1952-1956, Elizabeth II was the Queen of Pakistan. Therefore, the Queen’s demise brings to an end the last living link with the early years of our nation’s constitutional history.

However, not surprisingly, some discordant notes have been struck in Pakistan. The line of attack by the critics runs thus: since the British Empire was synonymous with conquest, colonial exploitation, racism and slavery, therefore the unrepentant Queen, as the symbol of that oppressive edifice, should neither be mourned nor is she worthy of any praise.

No doubt the proponents of this approach subscribe to Shakespeare’s memorable line, “the sins of the father are to be laid upon the children.” However, while literary license was available to the Bard of Avon to consider one generation culpable for the acts of its predecessor generations, for us lesser mortals the rule is a simple one: each person is liable only for his/her own acts of commission and omission. Law, equity, morality and logic demand no less.

By this token, how can Elizabeth II be held responsible for any crimes, excesses or infractions that were committed on the orders of British governments during the 18th to 20th centuries? It defies logic that anyone with a modicum of grasp of the principles of law and equity would subscribe to such a view.

Ascribing such guilt to the Queen is a flawed proposition for several reasons. First, from 1688 onwards the UK began transitioning towards a constitutional monarchy and political power steadily moved from Buckingham Palace to 10 Downing Street. Thus, by the 19th century, Queen Victoria may well have been Queen of the UK and Empress of India, but she only reigned as a figurehead monarch, and the actual power of running her vast dominions was vested in the British prime minister.

Therefore, can the British monarchs of the preceding three centuries be considered liable for actions which may well have been taken in their name, but only on the authority, and by the consent, of their fully empowered prime ministers? If common sense militates against an affirmative answer, then how can the Queen be taken to task on this count?

Second, as a constitutional head-of-state, did the Queen have the power and authority to apologise for the excesses of previous British governments? The simple answer is, absolutely not! The Queen was bound to act on the advice of her prime ministers on this matter, as she was on all other matters of statecraft, and only the prime minister of the day could have decided whether or not to apologise on behalf of the British government.

Third, is it sensible to judge the actions of previous generations on the touchstone of present-day principles which were absent in previous centuries? For example, concepts such as the rule of law, anti-racism, non-discrimination and the protection of fundamental human rights attained worldwide currency in the 20th century. Before then, these principles were conspicuous only by their absence.

Therefore, should the actions of rulers and statesmen of those earlier times, like Sultan Abdul Hamid or Emperor Napoleon or Tsar Alexander or Otto von Bismarck or Count Metternich, be viewed through the prism of our modern-day lens? If so, then should not the current governments of Turkey, France, Russia, Germany and Austria be made to apologise and atone for the centuries-old decisions of their previous leaders? Or are the French, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, Belgian and German governments absolved of the sins of colonialism perpetrated by their predecessors and only the British are to be held to account?

Interestingly, the Pakistani state lays claim to be the inheritor of the Mughal Empire and on that basis a demand has been made for the return of the Kohinoor Diamond from the UK. By that token, should the government of Pakistan, being the self-avowed successor of the Mughal state, apologise to the government of India for the conquest of India by the Mughals and for their plunder of Indian resources?

Ludicrous as this line of reasoning appears, what is good for the goose is good for the gander; if the Queen should have apologised for the sins of previous British governments, then surely the Pakistani state cannot shirk its responsibility for the darker side of Mughal rule over India.

As Pakistanis we also need to chew on another hard fact. Had the British colonial government chosen to transfer power to a unitary Indian state in 1947, the inhabitants of present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh may well have gone under perpetual Hindu yoke. The Quaid masterfully won the case for Pakistan, but it cannot be denied that it was the British government of Clement Attlee which agreed to separate the Subcontinent into two and to carve out a brand new country from the ancient territory of India.

Therefore, it scarcely behooves us to indulge in an outright condemnation of British rule over India and to arraign the former Queen of Pakistan on an arguably specious basis.

For many Pakistanis with an interest in our nation’s history, there is an added sense of remembrance. From 1947-1956, Pakistan had dominion status and it functioned as a constitutional monarchy. For four of those years, from 1952-1956, Elizabeth II was the Queen of Pakistan. Therefore, the Queen’s demise brings to an end the last living link with the early years of our nation’s constitutional history.

However, not surprisingly, some discordant notes have been struck in Pakistan. The line of attack by the critics runs thus: since the British Empire was synonymous with conquest, colonial exploitation, racism and slavery, therefore the unrepentant Queen, as the symbol of that oppressive edifice, should neither be mourned nor is she worthy of any praise.

No doubt the proponents of this approach subscribe to Shakespeare’s memorable line, “the sins of the father are to be laid upon the children.” However, while literary license was available to the Bard of Avon to consider one generation culpable for the acts of its predecessor generations, for us lesser mortals the rule is a simple one: each person is liable only for his/her own acts of commission and omission. Law, equity, morality and logic demand no less.

By this token, how can Elizabeth II be held responsible for any crimes, excesses or infractions that were committed on the orders of British governments during the 18th to 20th centuries? It defies logic that anyone with a modicum of grasp of the principles of law and equity would subscribe to such a view.

Ascribing such guilt to the Queen is a flawed proposition for several reasons. First, from 1688 onwards the UK began transitioning towards a constitutional monarchy and political power steadily moved from Buckingham Palace to 10 Downing Street. Thus, by the 19th century, Queen Victoria may well have been Queen of the UK and Empress of India, but she only reigned as a figurehead monarch, and the actual power of running her vast dominions was vested in the British prime minister.

Therefore, can the British monarchs of the preceding three centuries be considered liable for actions which may well have been taken in their name, but only on the authority, and by the consent, of their fully empowered prime ministers? If common sense militates against an affirmative answer, then how can the Queen be taken to task on this count?

Second, as a constitutional head-of-state, did the Queen have the power and authority to apologise for the excesses of previous British governments? The simple answer is, absolutely not! The Queen was bound to act on the advice of her prime ministers on this matter, as she was on all other matters of statecraft, and only the prime minister of the day could have decided whether or not to apologise on behalf of the British government.

Third, is it sensible to judge the actions of previous generations on the touchstone of present-day principles which were absent in previous centuries? For example, concepts such as the rule of law, anti-racism, non-discrimination and the protection of fundamental human rights attained worldwide currency in the 20th century. Before then, these principles were conspicuous only by their absence.

Therefore, should the actions of rulers and statesmen of those earlier times, like Sultan Abdul Hamid or Emperor Napoleon or Tsar Alexander or Otto von Bismarck or Count Metternich, be viewed through the prism of our modern-day lens? If so, then should not the current governments of Turkey, France, Russia, Germany and Austria be made to apologise and atone for the centuries-old decisions of their previous leaders? Or are the French, Spanish, Dutch, Italian, Belgian and German governments absolved of the sins of colonialism perpetrated by their predecessors and only the British are to be held to account?

Interestingly, the Pakistani state lays claim to be the inheritor of the Mughal Empire and on that basis a demand has been made for the return of the Kohinoor Diamond from the UK. By that token, should the government of Pakistan, being the self-avowed successor of the Mughal state, apologise to the government of India for the conquest of India by the Mughals and for their plunder of Indian resources?

Ludicrous as this line of reasoning appears, what is good for the goose is good for the gander; if the Queen should have apologised for the sins of previous British governments, then surely the Pakistani state cannot shirk its responsibility for the darker side of Mughal rule over India.

As Pakistanis we also need to chew on another hard fact. Had the British colonial government chosen to transfer power to a unitary Indian state in 1947, the inhabitants of present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh may well have gone under perpetual Hindu yoke. The Quaid masterfully won the case for Pakistan, but it cannot be denied that it was the British government of Clement Attlee which agreed to separate the Subcontinent into two and to carve out a brand new country from the ancient territory of India.

Therefore, it scarcely behooves us to indulge in an outright condemnation of British rule over India and to arraign the former Queen of Pakistan on an arguably specious basis.