April 13, 1919 witnessed one of the most gruesome events of colonial violence on the Indian subcontinent. On this day, hundreds of families gathered at Jalianwala Bagh, a park in Amritsar, to celebrate the spring festival of Baisakhi. The celebrations were being held in defiance of the notorious Rowlatt Act which forbade public gatherings in the Punjab. As a response, colonial officials cordoned off the park with their troops, and ordered indiscriminate firing on the crowd. Official death toll from the incident was 379 while nationalist forces claimed that over a thousand people lost their lives in the horrific massacre.

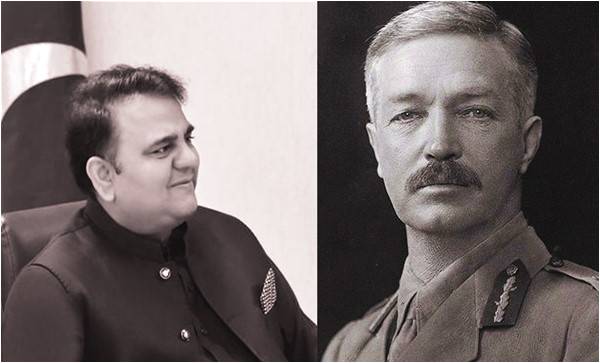

In 2013, the British Prime Minister David Cameron visited the site of the massacre and offered his “respects” but stopped short of a public apology. The centenary of the event this year is leading to renewed calls to the British government to apologise for one of the darkest chapters in its history. An apology was also demanded by Pakistan’s Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry, a rather bizarre move since the country has disavowed its shared anti-colonial history, including repressing the tragedy of the Amritsar Massacre as it does not neatly coincide with the state’s narrative of Muslim victimhood.

The centenary of the massacre is an opportunity for us to not only grapple with the scale of violence carried out in our past, but also recognise that despite our collective amnesia, the logic and methods of colonial governance continue to shape our contemporary moment. Moreover, it is critical to challenge the notion that the Amritsar Massacre was an exception to the “civilizing mission” of the British and place it in a continuum of the systematic oppression, humiliation and violence practiced by the colonial state.

For example, the massacre in Amritsar was preceded by mass unrest in the Punjab in the aftermath of the First World War. Punjabi soldiers were a central force in Britain’s war efforts. Yet, the end of the war led to a sudden demobilisation of the military, rendering hundreds of former soldiers unemployed. A sense of betrayal prevalent in the country was further amplified by increasing price hikes and unemployment that gripped the Indian economy. It was clear that India would have to bear the costs of the Inter-European conflict, as Britain tried to reorient its economy away from exigencies of the war.

Pervasive resentment against deteriorating conditions of everyday life and growing awareness of how India was subsidising the British post-war reconstruction ignited protests across the Punjab. These anti-colonial protests, later termed the “Punjab Disturbances,” led to the Rowlatt Act and the subsequent tragedy at Jallianwala Bagh.

The antagonism between the colonial state and the people, however, did not end with the massacre in Amritsar. A series of colonial practices followed that were aimed at subjugating and humiliating local populations as a response to their brief defiance of colonial power.

For instance, Gujranwala, a hotbed of anti-colonial activity, became the first city in the world in 1919 to be aerially bombarded during “peace time.” Soon after, the British began a bombing campaign in the restive Waziristan region at the border of Afghanistan to quell an anti-colonial insurgency. Between 2.5 and 7 tons of bombs were dropped every day for a full month, blurring judgment on whether the war had ended or only begun for the colonised people.

Apart from direct force, the colonial state also initiated other practices aimed at humiliating local populations. For instance, all students and faculty from the Santam Dharam College in Lahore were interned at the Red Fort and forced to stand in the sun for three hours. Their only crime was that they happened to study in a college whose walls were defaced with anti-government slogans. Such attribution of generalised guilt was also at work in the “saluting orders” issued by the local British official in Gujranwala. This particular order required all inhabitants of Gujranwala to leave their conveyances whenever they witnessed a European officer and stand in an upright position to salute.

Nasser Hussain’s excellent work on colonial violence in the Punjab shows how the primary target of “fanciful punishments” during the emergency were not particular individuals who committed specific crimes. He argues that these acts cannot even be constituted within the economy of punishments, as their goal was intended to be elsewhere, that is towards the re-establishment of a fledgling colonial authority.

One can infer this from the statement given by General Dyer, the man responsible for ordering troops to fire indiscriminately at the crowd in Jalianwala Bagh. In one of the more glaring examples of the link between colonial violence and colonial vulnerability, General Dyer reiterated the logic of his actions in the following words: “I fired and continued to fire until the crowd dispersed, and I consider this is the least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect it was my duty to produce if I was to justify my action….There could be no question of undue severity.”

Apart from revealing the cruelty of the colonial administration, what is remarkable about this statement is that it demonstrates how public torture, humiliation and annihilation of Indian bodies were viewed as carefully choreographed spectacles intended to suppress anti-colonial sentiment.

Such incidents of excessive violence contain three key lessons for understanding colonial modernity. First, they demonstrate the central place of fear in colonial governance. The spectacular demonstration of violence was perceived as a disciplining mechanism to inculcate fear among the people. But as Mark Condos and Kim Wagner have recently shown in their work on Colonial Punjab, such terrifying episodes also revealed the fear felt by the colonial state when confronted with the mass of the colonised subjects, leading to paranoia that communicated its vulnerability through excessive violence.

Second, this mutual feeling of asymmetry meant that theories of a social contract or liberal rights never informed state-society relations in the colonies. Instead, a vast majority of subjects experienced colonial modernity as a proliferation of checkpoints, cantonments, jails and deferred rights. All of this was aimed at demarcating the space and time of the civilised (West) from the (colonised) barbarians who allegedly needed supervision from their colonial masters before they could be ready for the modern public sphere. Thus, in the colonies, the logic of war trumped the logic of rights.

Finally, this historical tracing of the event should shed light on why an apology from the British is a necessary but inadequate response to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. It is necessary, since an apology would finally force the British state to acknowledge the incredible forms of violence that structure its own history, one that it has continuously disavowed. Yet, an apology is inadequate because we are not speaking of a specific incident that stands out as an aberration to the general rule. Instead, we are engaging here with machines of violence built to subjugate and humiliate large swathes of the populations, machines whose infrastructure and rationale continue to impact the modern world.

What is worse is that the classic “West vs. Rest” divide no longer fully holds, as these machines have become part of the logic of postcolonial states that were once its victims. It is indeed tragic that the postcolonial states of India and Pakistan, who remember the Amritsar Massacre as a national wound, have incorporated the violent logics of colonial governance into their own administrative practices. For example, while the bombing campaign in Waziristan began under the British, the region has seen multiple military operations led by the Pakistani state since Independence, citing the colonial discourse of “unruly” and “threatening” populations. Similarly, the combination of overt violence and humiliation regularly meted out to Kashmiris at the hands of the Indian military led celebrated historian, Partha Chatterjee, to declare that the Indian state was repeating the violent legacy of General Dyer in Kashmir.

Such examples demonstrate how a fidelity to those who lost their lives in colonial violence cannot stop at mere reminders of specific instances from history. It has to also grapple with the lingering and sinister ‘remainders’ of this history that continue to haunt us in our disoriented present.

A commitment to fight against the humiliation imposed upon humanity today, whether it be racial, gendered, or economic, is the best way to honour the legacy of those who perished in Jallianwala and elsewhere, since it challenges the logic of dehumanisation that made such a massacre possible. Otherwise, we will remain trapped in a loop of violence and indignity where the egalitarian dreams of modernity are perpetually transformed into a never-ending nightmare for a vast majority of humanity.

The writer is an assistant professor at Forman Christian College

In 2013, the British Prime Minister David Cameron visited the site of the massacre and offered his “respects” but stopped short of a public apology. The centenary of the event this year is leading to renewed calls to the British government to apologise for one of the darkest chapters in its history. An apology was also demanded by Pakistan’s Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry, a rather bizarre move since the country has disavowed its shared anti-colonial history, including repressing the tragedy of the Amritsar Massacre as it does not neatly coincide with the state’s narrative of Muslim victimhood.

The centenary of the massacre is an opportunity for us to not only grapple with the scale of violence carried out in our past, but also recognise that despite our collective amnesia, the logic and methods of colonial governance continue to shape our contemporary moment. Moreover, it is critical to challenge the notion that the Amritsar Massacre was an exception to the “civilizing mission” of the British and place it in a continuum of the systematic oppression, humiliation and violence practiced by the colonial state.

A commitment to fight against the humiliation imposed upon humanity today, whether it be racial, gendered, or economic, is the best way to honour the legacy of those who perished in Jallianwala

For example, the massacre in Amritsar was preceded by mass unrest in the Punjab in the aftermath of the First World War. Punjabi soldiers were a central force in Britain’s war efforts. Yet, the end of the war led to a sudden demobilisation of the military, rendering hundreds of former soldiers unemployed. A sense of betrayal prevalent in the country was further amplified by increasing price hikes and unemployment that gripped the Indian economy. It was clear that India would have to bear the costs of the Inter-European conflict, as Britain tried to reorient its economy away from exigencies of the war.

Pervasive resentment against deteriorating conditions of everyday life and growing awareness of how India was subsidising the British post-war reconstruction ignited protests across the Punjab. These anti-colonial protests, later termed the “Punjab Disturbances,” led to the Rowlatt Act and the subsequent tragedy at Jallianwala Bagh.

The antagonism between the colonial state and the people, however, did not end with the massacre in Amritsar. A series of colonial practices followed that were aimed at subjugating and humiliating local populations as a response to their brief defiance of colonial power.

For instance, Gujranwala, a hotbed of anti-colonial activity, became the first city in the world in 1919 to be aerially bombarded during “peace time.” Soon after, the British began a bombing campaign in the restive Waziristan region at the border of Afghanistan to quell an anti-colonial insurgency. Between 2.5 and 7 tons of bombs were dropped every day for a full month, blurring judgment on whether the war had ended or only begun for the colonised people.

Apart from direct force, the colonial state also initiated other practices aimed at humiliating local populations. For instance, all students and faculty from the Santam Dharam College in Lahore were interned at the Red Fort and forced to stand in the sun for three hours. Their only crime was that they happened to study in a college whose walls were defaced with anti-government slogans. Such attribution of generalised guilt was also at work in the “saluting orders” issued by the local British official in Gujranwala. This particular order required all inhabitants of Gujranwala to leave their conveyances whenever they witnessed a European officer and stand in an upright position to salute.

Nasser Hussain’s excellent work on colonial violence in the Punjab shows how the primary target of “fanciful punishments” during the emergency were not particular individuals who committed specific crimes. He argues that these acts cannot even be constituted within the economy of punishments, as their goal was intended to be elsewhere, that is towards the re-establishment of a fledgling colonial authority.

One can infer this from the statement given by General Dyer, the man responsible for ordering troops to fire indiscriminately at the crowd in Jalianwala Bagh. In one of the more glaring examples of the link between colonial violence and colonial vulnerability, General Dyer reiterated the logic of his actions in the following words: “I fired and continued to fire until the crowd dispersed, and I consider this is the least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect it was my duty to produce if I was to justify my action….There could be no question of undue severity.”

Apart from revealing the cruelty of the colonial administration, what is remarkable about this statement is that it demonstrates how public torture, humiliation and annihilation of Indian bodies were viewed as carefully choreographed spectacles intended to suppress anti-colonial sentiment.

Such incidents of excessive violence contain three key lessons for understanding colonial modernity. First, they demonstrate the central place of fear in colonial governance. The spectacular demonstration of violence was perceived as a disciplining mechanism to inculcate fear among the people. But as Mark Condos and Kim Wagner have recently shown in their work on Colonial Punjab, such terrifying episodes also revealed the fear felt by the colonial state when confronted with the mass of the colonised subjects, leading to paranoia that communicated its vulnerability through excessive violence.

Second, this mutual feeling of asymmetry meant that theories of a social contract or liberal rights never informed state-society relations in the colonies. Instead, a vast majority of subjects experienced colonial modernity as a proliferation of checkpoints, cantonments, jails and deferred rights. All of this was aimed at demarcating the space and time of the civilised (West) from the (colonised) barbarians who allegedly needed supervision from their colonial masters before they could be ready for the modern public sphere. Thus, in the colonies, the logic of war trumped the logic of rights.

Finally, this historical tracing of the event should shed light on why an apology from the British is a necessary but inadequate response to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. It is necessary, since an apology would finally force the British state to acknowledge the incredible forms of violence that structure its own history, one that it has continuously disavowed. Yet, an apology is inadequate because we are not speaking of a specific incident that stands out as an aberration to the general rule. Instead, we are engaging here with machines of violence built to subjugate and humiliate large swathes of the populations, machines whose infrastructure and rationale continue to impact the modern world.

What is worse is that the classic “West vs. Rest” divide no longer fully holds, as these machines have become part of the logic of postcolonial states that were once its victims. It is indeed tragic that the postcolonial states of India and Pakistan, who remember the Amritsar Massacre as a national wound, have incorporated the violent logics of colonial governance into their own administrative practices. For example, while the bombing campaign in Waziristan began under the British, the region has seen multiple military operations led by the Pakistani state since Independence, citing the colonial discourse of “unruly” and “threatening” populations. Similarly, the combination of overt violence and humiliation regularly meted out to Kashmiris at the hands of the Indian military led celebrated historian, Partha Chatterjee, to declare that the Indian state was repeating the violent legacy of General Dyer in Kashmir.

Such examples demonstrate how a fidelity to those who lost their lives in colonial violence cannot stop at mere reminders of specific instances from history. It has to also grapple with the lingering and sinister ‘remainders’ of this history that continue to haunt us in our disoriented present.

A commitment to fight against the humiliation imposed upon humanity today, whether it be racial, gendered, or economic, is the best way to honour the legacy of those who perished in Jallianwala and elsewhere, since it challenges the logic of dehumanisation that made such a massacre possible. Otherwise, we will remain trapped in a loop of violence and indignity where the egalitarian dreams of modernity are perpetually transformed into a never-ending nightmare for a vast majority of humanity.

The writer is an assistant professor at Forman Christian College