Last Tuesday I had dinner with my old college roommate. Henry is a white, middle-class American who grew up playing sports in the suburbs, and over the years I’ve used him as my central barometer for what White America is thinking at any given time. This admittedly problematic impulse probably began in the first second when I met him. I had barely finished lugging two heavy suitcases up to our shared rooms when the front door flung opened unsolicited. Henry stood there with an outstretched hand. ‘Sup,” he said.

Excited as I was about college and time away from home, I was very nervous about the kind of roommate I would get. Never having shared a room, I spent months terrified that I’d have to live with the worst caricature of an American: a racist, homophobic lacrosse player who had a rotation of one-night stands and never cleaned the bathroom. Henry, I am eternally grateful, was none of these (except a lacrosse player but you can’t win ‘em all). In retrospect he must have been as unsure of me as I was of him. We spent the first hour awkwardly trying to get to know each other and I gathered he is one of three kids, had recently moved colleges so that he could to be closer to his ailing mother, and that his brother was at the time serving as a combatant in Iraq. It was 2004 and the Iraq war was new, so the revelation made me nervous. Here was a flesh and blood example of the US army families I saw referred to on TV speeches, and my assumptions about his biases scared me. But he was nothing like I feared. He was intelligent and thoughtful; we remained friends through college and the fifteen years since.

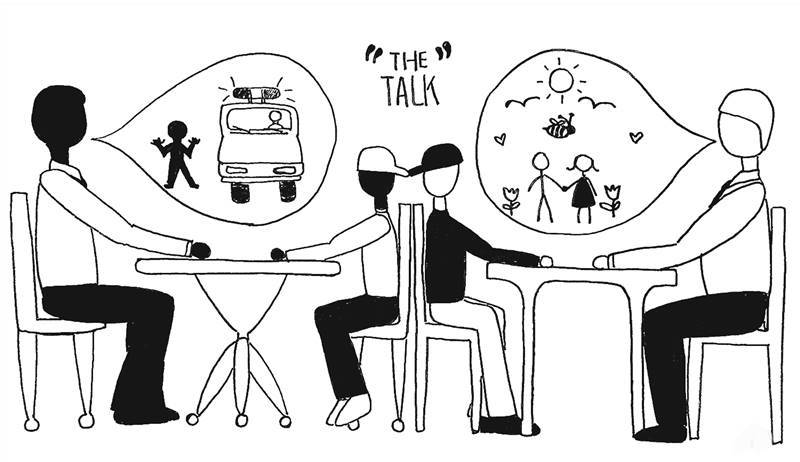

At our most recent dinner we began talking about the concept of “privilege”. As as a straight, white, middle-class, educated, professional adult American male, Henry is perceived to be the recipient of almost all of the privilege the U.S can afford to confer on one person. He confessed that although he understood why people were talking more and more openly about implicit biases, he sometimes felt shut out of the conversation, as if his being and who he is precluded him from having an opinion at all. In a way he is right. But the idea that this might have something to do with the fact that everyone in the world had already heard from white men for centuries didn’t sit well with him. He didn’t grow up wealthy, he reminded me. Had to work all through high-school and college, and he graduated with large student debts that he only recently began paying off after nearly half a decade of drawing pay cheques. Why then, he asked, can someone tell me that I’ve had a privileged upbringing?

It’s a reasonable question, and not for the first time I found myself having to explain privilege to a white man and not knowing quite how to do it. You begin by asserting than privilege is not just about money. The easiest way for me to understand the concept is that privilege is when you think something isn’t a problem simply because it isn’t a problem for you. I don’t worry about where my next meal is coming from, or where I can find shelter to spend the night, or worry about having to feed a dependent. My obsession with diets aside, I remain a man of imposing proportions and so I don’t often have to think about my safety walking alone late at night, or take precaution to avoid being touched without permission. Nearly all the women I know do not take this for granted. These are only a few of my privileges as an educated, employed man.

But I also reminded Henry that despite the fact that I was in the U.S completely legally, for the years that he and I were roommates I was questioned for hours at airports, wasn’t allowed to leave the country without checking into immigration, formulated travel plans based on visa requirements and in general lived under the assumption that in the eye of the American state I was “guilty” until I proved otherwise. Even with my white college friends - Henry and some professors included - I felt the invisible pressure to prove that I was not a “terrorist”, that I was the “right” kind of foreigner, whatever that means. White straight men called Henry did not have to do that. That’s his privilege. We eventually began debating the terminology of political correctness and representation. He wondered aloud why it was that everyone was so concerned about “representation, particularly trans folks or “people of colour”.

Its then that I realized that as close as we are are friends, we have tremendously different lived experiences. Henry can go to most any country turn on the TV and count on seeing content from his home country, complete with people with his skin tone telling a version of history that takes their centrality to it for granted. Calling him out on that is not taking away from any hardships he’s faced, but rather asking him to see that it is not merely bad luck why other races or people can’t do the same thing that he can. There is a reason a white person believes themselves to be in one group and “people of colour” to be in another. Its one born of centuries of endemic disenfranchisement. The system breeds the same ugliness as when the President of America told a group of non-white Congresswomen this week to “go back to where they came from.” He thinks they are different, and it’s not a long way from “different” to “lesser”.

But its not just white people. I’ve had to endure the most racist conversations with desi uncles and aunties all my life. Recently I had one aunty bemoaning racial or LGBT inclusivity in popular culture because they wondered “Why do people have to be so public about it? It’s not like I go onto rooftops shouting about who I am sleeping with?”

No, the world did that for you Shahista, because the moment you found a man to sleep with for life your parents threw you an expensive five-day party and patiently waited for you to get knocked up, after which they threw you another party. The world and its mating rituals were built for you to shout out about who you are sleeping with. LGBT folks don’t get that privilege.

So the next time someone talk to you about privilege, try not to recoil into a defensive ball. Be honest: which parts of your life have benefited from an advantage you didn’t even realize you had?

For the truth is that everyone’s problems are problems, even if they aren’t everyone’s problems. Even yours!

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

Excited as I was about college and time away from home, I was very nervous about the kind of roommate I would get. Never having shared a room, I spent months terrified that I’d have to live with the worst caricature of an American: a racist, homophobic lacrosse player who had a rotation of one-night stands and never cleaned the bathroom. Henry, I am eternally grateful, was none of these (except a lacrosse player but you can’t win ‘em all). In retrospect he must have been as unsure of me as I was of him. We spent the first hour awkwardly trying to get to know each other and I gathered he is one of three kids, had recently moved colleges so that he could to be closer to his ailing mother, and that his brother was at the time serving as a combatant in Iraq. It was 2004 and the Iraq war was new, so the revelation made me nervous. Here was a flesh and blood example of the US army families I saw referred to on TV speeches, and my assumptions about his biases scared me. But he was nothing like I feared. He was intelligent and thoughtful; we remained friends through college and the fifteen years since.

At our most recent dinner we began talking about the concept of “privilege”. As as a straight, white, middle-class, educated, professional adult American male, Henry is perceived to be the recipient of almost all of the privilege the U.S can afford to confer on one person. He confessed that although he understood why people were talking more and more openly about implicit biases, he sometimes felt shut out of the conversation, as if his being and who he is precluded him from having an opinion at all. In a way he is right. But the idea that this might have something to do with the fact that everyone in the world had already heard from white men for centuries didn’t sit well with him. He didn’t grow up wealthy, he reminded me. Had to work all through high-school and college, and he graduated with large student debts that he only recently began paying off after nearly half a decade of drawing pay cheques. Why then, he asked, can someone tell me that I’ve had a privileged upbringing?

It’s a reasonable question, and not for the first time I found myself having to explain privilege to a white man and not knowing quite how to do it. You begin by asserting than privilege is not just about money. The easiest way for me to understand the concept is that privilege is when you think something isn’t a problem simply because it isn’t a problem for you. I don’t worry about where my next meal is coming from, or where I can find shelter to spend the night, or worry about having to feed a dependent. My obsession with diets aside, I remain a man of imposing proportions and so I don’t often have to think about my safety walking alone late at night, or take precaution to avoid being touched without permission. Nearly all the women I know do not take this for granted. These are only a few of my privileges as an educated, employed man.

But its not just white people. I’ve had to endure the most racist conversations with desi uncles and aunties all my life

But I also reminded Henry that despite the fact that I was in the U.S completely legally, for the years that he and I were roommates I was questioned for hours at airports, wasn’t allowed to leave the country without checking into immigration, formulated travel plans based on visa requirements and in general lived under the assumption that in the eye of the American state I was “guilty” until I proved otherwise. Even with my white college friends - Henry and some professors included - I felt the invisible pressure to prove that I was not a “terrorist”, that I was the “right” kind of foreigner, whatever that means. White straight men called Henry did not have to do that. That’s his privilege. We eventually began debating the terminology of political correctness and representation. He wondered aloud why it was that everyone was so concerned about “representation, particularly trans folks or “people of colour”.

Its then that I realized that as close as we are are friends, we have tremendously different lived experiences. Henry can go to most any country turn on the TV and count on seeing content from his home country, complete with people with his skin tone telling a version of history that takes their centrality to it for granted. Calling him out on that is not taking away from any hardships he’s faced, but rather asking him to see that it is not merely bad luck why other races or people can’t do the same thing that he can. There is a reason a white person believes themselves to be in one group and “people of colour” to be in another. Its one born of centuries of endemic disenfranchisement. The system breeds the same ugliness as when the President of America told a group of non-white Congresswomen this week to “go back to where they came from.” He thinks they are different, and it’s not a long way from “different” to “lesser”.

But its not just white people. I’ve had to endure the most racist conversations with desi uncles and aunties all my life. Recently I had one aunty bemoaning racial or LGBT inclusivity in popular culture because they wondered “Why do people have to be so public about it? It’s not like I go onto rooftops shouting about who I am sleeping with?”

No, the world did that for you Shahista, because the moment you found a man to sleep with for life your parents threw you an expensive five-day party and patiently waited for you to get knocked up, after which they threw you another party. The world and its mating rituals were built for you to shout out about who you are sleeping with. LGBT folks don’t get that privilege.

So the next time someone talk to you about privilege, try not to recoil into a defensive ball. Be honest: which parts of your life have benefited from an advantage you didn’t even realize you had?

For the truth is that everyone’s problems are problems, even if they aren’t everyone’s problems. Even yours!

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com