“What do you want to be when you grow up?” I remember being asked in grade nine, to which I had replied, “an astrophysicist.” It was late 2004. Before then, I was as clueless and as undecided as are most other students in grade nine. Academics, at the time, I viewed primarily as a means to an end: to get good enough grades to secure a decent job.

However, in the summer of 2004, I watched two movies that would not only be the impetus for my future academic choices but also become the start of what would completely upend my view on life, the universe and everything else in between.

The first one was ‘Contact’ which is a movie adaptation of the sci-fi book by the brilliant astrophysicist Carl Sagan. Its storyline was enough of an inspiration to get me interested in studying sciences.

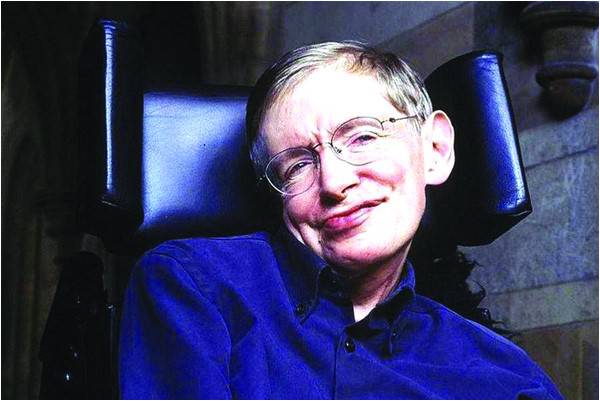

But the moment that definitely got me hooked on science, particularly physics, came from another movie simply titled ‘Hawking.’

I still remember the profound effect one of the scenes in the movie had on me. In this scene, a frail young Stephen Hawking, barely able to stand and staggering on with the help of a cane, stops dead in the middle of the street and, in a moment of break down and vulnerability but decided inspiration, draws out the geometrical representation of his theory on the road.

This level of interest in and dedication to a cause left an interminable impression and, even though I couldn’t pursue astrophysics, singularly sparked my lifelong affair with sciences and scientific research.

Professor Stephen Hawking’s utter commitment to his ideas and his work despite his completely debilitating affliction inspires an unfailing sense of purpose.That to me is his real legacy and is what makes him one of the best of humanity.

His inspirational story is not all that made him the great man that he was. Professor Hawking’s genius shone through both his feats in physics and his efforts for making science accessible to the public. In the following words, I have attempted to recount a brief history of his life and work.

As a scientist, Dr Hawking spent his life addressing the profound questions arising out of Einstein’s greatest theory, the theory of gravity, general relativity.

Einstein’s general relativity, revealed the true nature of space and time. But it also predicted something so odd that he himself never really accepted it. The theory predicted that if enough mass was concentrated at one point, the space around it would sag like a mattress and bend so much as to form a closed region – like a sinkhole – with so much gravity that not even light could escape from it.

It was Dr Hawking was instrumental in making these imagined entities – the black holes – more than just an academic curiosity.

It was previously thought that black holes were extremely rare in the universe and that it was highly unlikely that we would ever observe one. This was because the extreme bending of space required, according to the math, specialized and exceptionally difficult to occur pre-conditions.

However, in his 1966 doctoral thesis, Hawking managed to prove that black holes could be produced under many different, much general, pre-conditions and that the universe should be peppered with them. Indeed, as we now know, there’s a black hole at the centre of almost every galaxy, even our very own Milky Way.

Moreover, in 1970, Dr Hawking, in collaboration with mathematician and physicist Roger Penrose, showed that time and space also had a beginning. In other words, they showed that the universe had a beginning: it was the Big Bang.

In 1974, Dr Hawking came up with an idea that overturned another generally accepted truth about black holes. Physicists had previously thought that things falling into the black holes would make them bulk up and increase in size. But Hawking showed that one thing could escape the immense gravitational pull of a black hole: heat. He showed that black holes were hot – they had a temperature and that would give them a faint glow. This, he revealed, would make the black holes leak energy in the form of radiation and get smaller and smaller until they exploded.

This idea that bears his name – Hawking radiation – might not seem very much on its own but this is one of his crowning achievements because of what it means for the discipline of physics.

Modern physics rests on two pillars: two vastly powerful and highly successful models of reality. One is quantum field theory which deals with everything smaller than atoms. It can explain everything from light, electricity, chemical reactions and nuclear radiation to the basic constituents of matter: the sub-atomic particles. The other theory deals with the universe at the largest of scales - that is, it explains how everything from planets and stars to the galaxies and the largest superstructures in the universe behave through the interplay of space, time and gravity. This is the same Einsteinian theory mentioned above: general relativity.

These two theories together explain almost everything that we have ever observed, measured, or experimented with. But there is a problem. These two ideas do not sit well together; they break down when stretched to the extremes and so they cannot be stitched into a single overarching framework. If they could be merged, all phenomena in the universe would be reducible to one single equation: the so-called theory of everything.

Up until 1974, all attempts to reconcile the two ideas had failed - the two pillars stood too far apart. But Hawking had a way of bringing vastly separate worlds together. The brilliance of his idea lay in the fact that he was able to combine the features of quantum mechanics like light and temperature and the features of relativity into the idea of Hawking radiation. Although it didn’t solve everything, the idea became an important first step towards the formulation of a theory of everything.

Dr Hawking’s uncanny knack of overturning previously accepted notions did not just extend to his scientific work. He was also instrumental in bringing down an unsaid precept to which the scientific community had stuck. Up until the late 1980s, scientists, particularly physicists, believed that modern science was much too complex and unlike day-to-day experience to be effectively communicated to the public. Scientists mostly only made brief media comments and any scientific books written for public consumption dealt with the concepts tersely and in fairly technical terms.

In 1988 Dr Hawking published his most popular book A Brief History of Time. Here, he gave an overview of the history of the universe starting from the Big Bang. He described intricate concepts in terms understandable by any non-technical person familiar with high school science.

The book stayed on the London-Times bestseller list for four years, beating all expectations that such a book would not garner much public response and starting a gold rush of popular science books by other eminent scientists.

Professor Hawking and Carl Sagan both were influential in bringing down the barriers between scientists and researchers and the public and inspired many to join research and STEM fields.

Dr Hawking was particularly media savvy. He regularly appeared on prominent public platforms. And through his appearances in documentaries and science lectures he always remained devoted to furthering public understanding of science.

It took a lot of preparation and months of planning before Dr Hawking could travel from one place to another. Nonetheless he actually made it a point to be the most socially immersive scientist of his time. He regularly appeared in various TV dramas and comedy shows. His most notable appearance being several cameos in the comedy show The Big Bang Theory. He was as much idolised by the popular culture, having been portrayed in biopics about his life, several guest appearances in cartoon shows like Futurama and the Simpsons and depictions in numerous comics, newspapers and books.

Professor Hawking can be considered a true heir of Einstein’s legacy as he not only extended the theory of relativity but also posed many clever questions associated with it. Some of the debates that he started still rage on 40 years later.

Perhaps then, it was fitting that he died on the day of Einstein’s birth. Because Time, as both him and Einstein told us, is relative.

However, in the summer of 2004, I watched two movies that would not only be the impetus for my future academic choices but also become the start of what would completely upend my view on life, the universe and everything else in between.

The first one was ‘Contact’ which is a movie adaptation of the sci-fi book by the brilliant astrophysicist Carl Sagan. Its storyline was enough of an inspiration to get me interested in studying sciences.

But the moment that definitely got me hooked on science, particularly physics, came from another movie simply titled ‘Hawking.’

I still remember the profound effect one of the scenes in the movie had on me. In this scene, a frail young Stephen Hawking, barely able to stand and staggering on with the help of a cane, stops dead in the middle of the street and, in a moment of break down and vulnerability but decided inspiration, draws out the geometrical representation of his theory on the road.

This level of interest in and dedication to a cause left an interminable impression and, even though I couldn’t pursue astrophysics, singularly sparked my lifelong affair with sciences and scientific research.

Professor Stephen Hawking’s utter commitment to his ideas and his work despite his completely debilitating affliction inspires an unfailing sense of purpose.That to me is his real legacy and is what makes him one of the best of humanity.

His inspirational story is not all that made him the great man that he was. Professor Hawking’s genius shone through both his feats in physics and his efforts for making science accessible to the public. In the following words, I have attempted to recount a brief history of his life and work.

As a scientist, Dr Hawking spent his life addressing the profound questions arising out of Einstein’s greatest theory, the theory of gravity, general relativity.

Einstein’s general relativity, revealed the true nature of space and time. But it also predicted something so odd that he himself never really accepted it. The theory predicted that if enough mass was concentrated at one point, the space around it would sag like a mattress and bend so much as to form a closed region – like a sinkhole – with so much gravity that not even light could escape from it.

It was Dr Hawking was instrumental in making these imagined entities – the black holes – more than just an academic curiosity.

It was previously thought that black holes were extremely rare in the universe and that it was highly unlikely that we would ever observe one. This was because the extreme bending of space required, according to the math, specialized and exceptionally difficult to occur pre-conditions.

However, in his 1966 doctoral thesis, Hawking managed to prove that black holes could be produced under many different, much general, pre-conditions and that the universe should be peppered with them. Indeed, as we now know, there’s a black hole at the centre of almost every galaxy, even our very own Milky Way.

Moreover, in 1970, Dr Hawking, in collaboration with mathematician and physicist Roger Penrose, showed that time and space also had a beginning. In other words, they showed that the universe had a beginning: it was the Big Bang.

In 1974, Dr Hawking came up with an idea that overturned another generally accepted truth about black holes. Physicists had previously thought that things falling into the black holes would make them bulk up and increase in size. But Hawking showed that one thing could escape the immense gravitational pull of a black hole: heat. He showed that black holes were hot – they had a temperature and that would give them a faint glow. This, he revealed, would make the black holes leak energy in the form of radiation and get smaller and smaller until they exploded.

This idea that bears his name – Hawking radiation – might not seem very much on its own but this is one of his crowning achievements because of what it means for the discipline of physics.

Modern physics rests on two pillars: two vastly powerful and highly successful models of reality. One is quantum field theory which deals with everything smaller than atoms. It can explain everything from light, electricity, chemical reactions and nuclear radiation to the basic constituents of matter: the sub-atomic particles. The other theory deals with the universe at the largest of scales - that is, it explains how everything from planets and stars to the galaxies and the largest superstructures in the universe behave through the interplay of space, time and gravity. This is the same Einsteinian theory mentioned above: general relativity.

These two theories together explain almost everything that we have ever observed, measured, or experimented with. But there is a problem. These two ideas do not sit well together; they break down when stretched to the extremes and so they cannot be stitched into a single overarching framework. If they could be merged, all phenomena in the universe would be reducible to one single equation: the so-called theory of everything.

Up until 1974, all attempts to reconcile the two ideas had failed - the two pillars stood too far apart. But Hawking had a way of bringing vastly separate worlds together. The brilliance of his idea lay in the fact that he was able to combine the features of quantum mechanics like light and temperature and the features of relativity into the idea of Hawking radiation. Although it didn’t solve everything, the idea became an important first step towards the formulation of a theory of everything.

Dr Hawking’s uncanny knack of overturning previously accepted notions did not just extend to his scientific work. He was also instrumental in bringing down an unsaid precept to which the scientific community had stuck. Up until the late 1980s, scientists, particularly physicists, believed that modern science was much too complex and unlike day-to-day experience to be effectively communicated to the public. Scientists mostly only made brief media comments and any scientific books written for public consumption dealt with the concepts tersely and in fairly technical terms.

In 1988 Dr Hawking published his most popular book A Brief History of Time. Here, he gave an overview of the history of the universe starting from the Big Bang. He described intricate concepts in terms understandable by any non-technical person familiar with high school science.

The book stayed on the London-Times bestseller list for four years, beating all expectations that such a book would not garner much public response and starting a gold rush of popular science books by other eminent scientists.

Professor Hawking and Carl Sagan both were influential in bringing down the barriers between scientists and researchers and the public and inspired many to join research and STEM fields.

Dr Hawking was particularly media savvy. He regularly appeared on prominent public platforms. And through his appearances in documentaries and science lectures he always remained devoted to furthering public understanding of science.

It took a lot of preparation and months of planning before Dr Hawking could travel from one place to another. Nonetheless he actually made it a point to be the most socially immersive scientist of his time. He regularly appeared in various TV dramas and comedy shows. His most notable appearance being several cameos in the comedy show The Big Bang Theory. He was as much idolised by the popular culture, having been portrayed in biopics about his life, several guest appearances in cartoon shows like Futurama and the Simpsons and depictions in numerous comics, newspapers and books.

Professor Hawking can be considered a true heir of Einstein’s legacy as he not only extended the theory of relativity but also posed many clever questions associated with it. Some of the debates that he started still rage on 40 years later.

Perhaps then, it was fitting that he died on the day of Einstein’s birth. Because Time, as both him and Einstein told us, is relative.