The ancient Greek philosopher, Socrates, would wander the agora- a public space for debate and discussion in the heart of Athens- seeking fellows for the intellectual discourses he used to conduct. One day, he came across a young man, called Euthydemus, who boasted of his knowledge of various subjects. The old Socrates, with his signature humility, didn’t challenge Euthydemus’ claims outright, instead, Socrates asked him a series of questions, unravelling his fragmented and disjointed information layer by layer, until the young man saw his inner ignorance. By the end of the discussion, the young man, Euthydemus, was not only cognizant of his limited knowledge but was also impressed by Socrates' method of thinking about one's form and function of thinking. “I cannot teach anybody anything,”the teacher of Plato and Xenophon is reported to have said, “I can only make them think”. The element which is missing the most from our education system today is the one that Socrates practised in the 5th century BCE. Instead of equipping our future generation with the lifelong skills of thinking critically and creatively, we are stuffing their heads with lots of information- information often so messy and muddled that they cannot make any sense of .

Sensing the gravity of this glooming reality, the Dosti Welfare Organization, a not-for-profit initiative that primarily works to educate street children in Pakistan, but also conducts, occasionally, literary and cultural events to breed a culture of book reading, debate, dialogue, and tolerance. Recently, with the help of some devoted academics and public intellectuals from the University of Peshawar and Edwards College, Peshawar, the organization steered a series of workshops on thinking and writing skills for university students. Like all its activities, the registration for this event was free. To the surprise of those who lament students’ disinterest in materials outside their curriculum, these workshops- despite the suffocating heat- received more attendees than the organisers had planned for.

“Some creatures possess qualities that humans don’t”a presenter of the workshop explained. “For example,” he continued, “birds can fly, while humans cannot; a tiger can run faster than humans, and a donkey can lift heavier weight than a strong man can; then what quality”, he asked, “has made man superior to them?”

“Thinking,” responded the students.

In most cases, test questions consist of the names of capitals and the currencies of less-known countries like Fiji, Laos, and Chad. One wonders how answering these tricky questions could help teach better

The speaker, while appreciating the students' responses, emphasized the importance of critical and creative thinking, especially in our context where the use of brute force is preferred to the use of rational thought and sound reasoning. The teacher referred to a quote from the Polish-British mathematician and philosopher, Jacob Bronowski, who had cogently distinguished between the use of brain and brawn: “Man masters nature not by force but by understanding.”

Reflecting upon the current state of society in Pakistan, the speaker recalled events that prtray a negative image of this nation as an ‘intolerant, irrational mob’.

He mentioned the events from lynching people inside the police stations and on university campuses to a mob threatening a woman whose attire contained prints of Arabic calligraphy and a lawyer, whose main job is, supposedly, to engage in critical reasoning and logical analysis, but he fell into scuffles with a fellow arguer in front of the camera on a live TV show.

More worrisome than that, this ignoble act, instead of making us alarmed regarding the shrinking space of tolerance and principled debate, won the attorney a massive fan following and earned him the status of a celebrity. This bitter reality shows where our society holds reason and rationality, and where it places violence and its perpetrators.

Regurgitation machines - from remembering to remembering

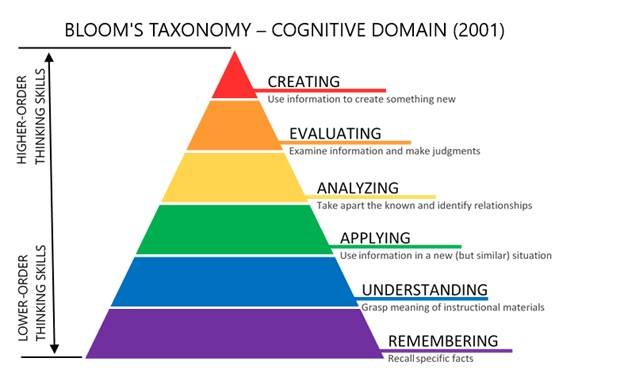

In the 1950s, the American educational psychologist, Benjamin Bloom, published his Taxonomy of Educational Objectives commonly known as Bloom’s Taxonomy. Bloom’s framework has been used by generations of school teachers and college instructors in their teaching to align their instruction and assessment with the levels of the cognitive processes and the goals they want their students to achieve.

Starting with remembering and ending with creation, the taxonomy, designed in the shape of a pyramid, lays the ground for educators to promote thinking skills among students- from lower-order to higher-order thinking- depending on their age and grade levels.

The taxonomy encompasses six levels, namely Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating. In most of our institutions of higher learning, tragically, the pyramid starts with remembering and ends, too, with remembering. As one student explained “Let alone other subjects, even when we study philosophy as a minor subject at university, the focus is on memorizing definitions, remembering the dates of birth and deaths of Western philosophers; and, in some cases, only names of the books they wrote. However, there is no practical engagement with the concepts of philosophy or the creation of new knowledge.

This teaching practice is somewhat unsurprising and even expected because the educators, more often than not, are selected based on their excellence in lower-order thinking skills especially Remembering, a skill that lies at the bottom of the pyramid.

Pounding square pegs into round holes - the recruiting system

The experience of candidates who had appeared in a variety of Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) based tests conducted by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Public Service Commission and other private testing agencies like the NTS, helped understand the current teaching standards of educators. For example, a graduate, who had an excellent academic record and belonged to the southern part of K.P., came across this question on his test, “Which university is closer to ‘Bari Imam’?”Since he had never lived in Islamabad, he didn’t know where or even what, ‘Bari Imam’ was let alone the distance to universities from it. And I am sure many folks living in Islamabad, whose thinking abilities couldn’t be questioned, won't be aware of the location of ‘Bari Imam’.

In most cases, the tests’ questions consist of the names of capitals and the currencies of less-known countries like Fiji, Laos, and Chad. One wonders as to how answering these tricky questions could help teach better, or for that matter, enable the crammer to perform any job that requires complex higher-order thinking skills.

After their recruitment, these ‘misfit square pegs’ then go on to reach the higher echelons of power, where they themselves become recruiters in the capacity of the head of a department or a senior officer.

Likewise, A student shared his experience of studying at a private boarding school in Bannu where they had horses for riding. Once a new principal came to the school who was feeling very proud of having his PhD degree in English. The learned principal wondered what were the horses doing in an educational institute. “Is this a school or a barn?”he asked. Due to his behaviour of neglect and abhorrence towards the horses, within a few months, all the ‘animals’ vanished from the school.

Quite recently, the same line of reasoning was used by the honourable Chief minister of KP, Ali Amin Gundapur, when he was justifying his government’s ‘envisioned’ sale of universities’ land in Mardan. “Do kids come (to universities) to play polo or to study? Why do these universities need such huge lands? Are they running horses in it?”

He said this in a video widely circulated on social media by his fans, who were impressed by his polemical skills and by not-so-fans, who were flabbergasted at the short-sightedness of a leader who promised great change.

“While we teach our students subjects that they might not need even once in their lives,”said a participant of the workshop “sadly, we don’t teach them a subject that they will need every day in their lives, that is, critical and creative thinking.”she lamented.

Isn’t it the right time we think about it?