Hardly a day goes by without a headline featuring a woman being killed in Pakistan. Oft-reported cases include violence committed in the name of 'honour'. Indeed, many don’t even make it to news reports.

According to Human Rights Watch, around 1,000 Pakistani women are annually murdered in the name of 'honour'. The causes behind these killings include, but aren’t limited to, ‘unacceptable’ amorous relationships, defiance of gender-specific spaces, brazenness in dressing, and pretty much anything that could be perceived as immoral.

Some argue that reporting 'honour' killings defames Pakistan, as if that means we shouldn’t raise our voice against a gory practice across the country, especially the tribal areas. While women from all ethnic groups have been victims of the so-called honour of their menfolk, my focus is the Pashtun society, where the centuries-old code of life, Pashtunwali, and the correlated nang (honour) continue to be misconstrued.

Pashtunwali is a complete ethical code for Pashtuns, guiding them in every aspect of life since prehistoric times. Even though some scholars argue that it has stemmed from the tenets of Islam, but the code dates back to ancient pre-Islamic times.

The code is instilled in every Pashtun since birth. It is said, to be a Pashtun is to observe Pashtunwali. The role of Pashtunwali in a Pashtun’s life is the same as religion in an ascetic life or the constitution for a patriot.

Pashtunwali is conventionally described as comprising three key concepts: melmastia (hospitality), badal (revenge), and nanawati (submission or asylum). Other aspects relate to toora (bravery), musawat (equality), bawar (trust), and nang. Fundamentally, all Pashtunwali ideals converge towards the latter.

According to Pashtunwali, the true idea of honour for men is safeguarding the respectability of women, who have to be protected from any physical or verbal harm. Integrity of fellow Pashtuns and the homeland also comes under honour. Pashtunwali requires every Pashtun to stand up against any injustice committed against a fellow Pashtun or any other human being.

Unfortunately, the idea of honour has been twisted and peddled as revolving around women, who, as a result, have been victimised for centuries. In a fair world, both men and women would be treated identically under the nang clauses, but instead women are predominantly scapegoated for men’s actions.

Paighor (taunt) often triggers Pashtun men to inflict violence on women over ‘honour’. Men in Pashtun society fear that other men will humiliate them with paighor for generations, to prevent which they resort to killing their own daughters and sisters. That’s their way to restoring the ‘honour’ of the tribe.

Pashtunwali reinforces patriarchy and, like any other patriarchal system, persecutes women. In a Pashtun society ‘honour’ is preserved through complete objectification of women, as a popular Pashto proverb goes: ‘A woman's use is either to cure your poverty or to settle a feud’.

Historically, Pashtunwali has been widely used to settle personal scores. Swara (marrying off virgins to settle disputes), walwar (accepting money for marrying off girls), ghag (violent proclamation that a virgin belongs to a man), and sharmuna (monetary penalty collected over ‘shameful’ acts) are some misogynistic traditions. Mateeza (a derogatory label stamped on a girl who elopes for love) mandates death at the hands of the women’s own family.

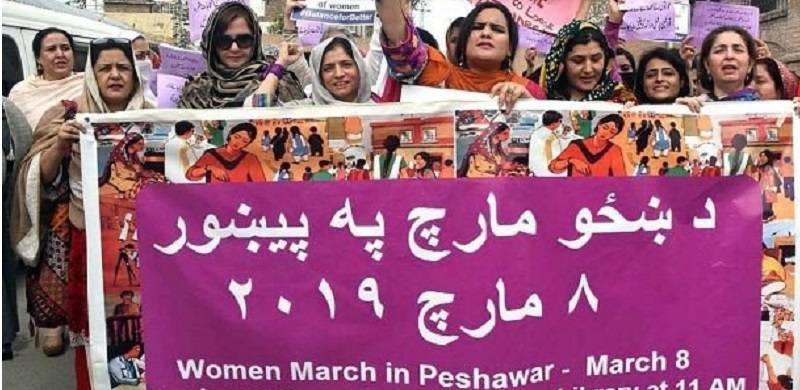

It’s time to redirect honour towards its actual meaning. We need to reclaim the meaning of nang, and redefine Pashtunwali as a gender-equal code for all Pashtun men and women—not a tool for men to subjugate women.

For, there is no honour in killing one’s own daughter just because she loved someone or married a man of her choice. Honour is raising your voice for the oppressed, standing beside those who are wronged. Today, nang for women would mean justice for the atrocities committed against them and a long overdue share in decision-making over policies that impact the entire womankind.

According to Human Rights Watch, around 1,000 Pakistani women are annually murdered in the name of 'honour'. The causes behind these killings include, but aren’t limited to, ‘unacceptable’ amorous relationships, defiance of gender-specific spaces, brazenness in dressing, and pretty much anything that could be perceived as immoral.

Some argue that reporting 'honour' killings defames Pakistan, as if that means we shouldn’t raise our voice against a gory practice across the country, especially the tribal areas. While women from all ethnic groups have been victims of the so-called honour of their menfolk, my focus is the Pashtun society, where the centuries-old code of life, Pashtunwali, and the correlated nang (honour) continue to be misconstrued.

Pashtunwali is a complete ethical code for Pashtuns, guiding them in every aspect of life since prehistoric times. Even though some scholars argue that it has stemmed from the tenets of Islam, but the code dates back to ancient pre-Islamic times.

The code is instilled in every Pashtun since birth. It is said, to be a Pashtun is to observe Pashtunwali. The role of Pashtunwali in a Pashtun’s life is the same as religion in an ascetic life or the constitution for a patriot.

Pashtunwali is conventionally described as comprising three key concepts: melmastia (hospitality), badal (revenge), and nanawati (submission or asylum). Other aspects relate to toora (bravery), musawat (equality), bawar (trust), and nang. Fundamentally, all Pashtunwali ideals converge towards the latter.

According to Pashtunwali, the true idea of honour for men is safeguarding the respectability of women, who have to be protected from any physical or verbal harm. Integrity of fellow Pashtuns and the homeland also comes under honour. Pashtunwali requires every Pashtun to stand up against any injustice committed against a fellow Pashtun or any other human being.

Unfortunately, the idea of honour has been twisted and peddled as revolving around women, who, as a result, have been victimised for centuries. In a fair world, both men and women would be treated identically under the nang clauses, but instead women are predominantly scapegoated for men’s actions.

Paighor (taunt) often triggers Pashtun men to inflict violence on women over ‘honour’. Men in Pashtun society fear that other men will humiliate them with paighor for generations, to prevent which they resort to killing their own daughters and sisters. That’s their way to restoring the ‘honour’ of the tribe.

Pashtunwali reinforces patriarchy and, like any other patriarchal system, persecutes women. In a Pashtun society ‘honour’ is preserved through complete objectification of women, as a popular Pashto proverb goes: ‘A woman's use is either to cure your poverty or to settle a feud’.

Historically, Pashtunwali has been widely used to settle personal scores. Swara (marrying off virgins to settle disputes), walwar (accepting money for marrying off girls), ghag (violent proclamation that a virgin belongs to a man), and sharmuna (monetary penalty collected over ‘shameful’ acts) are some misogynistic traditions. Mateeza (a derogatory label stamped on a girl who elopes for love) mandates death at the hands of the women’s own family.

It’s time to redirect honour towards its actual meaning. We need to reclaim the meaning of nang, and redefine Pashtunwali as a gender-equal code for all Pashtun men and women—not a tool for men to subjugate women.

For, there is no honour in killing one’s own daughter just because she loved someone or married a man of her choice. Honour is raising your voice for the oppressed, standing beside those who are wronged. Today, nang for women would mean justice for the atrocities committed against them and a long overdue share in decision-making over policies that impact the entire womankind.