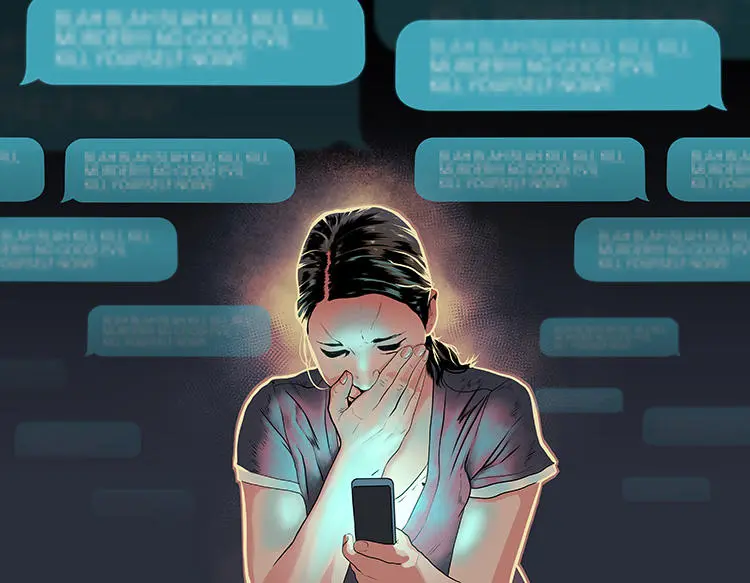

It cannot be denied that women and girls all over the world, especially in South Asia, are some of the worst impacted victims of digital violence. They are incredibly vulnerable to hate messages and sexual harassment, right up to rape and murder threats, on the Internet. Every single day, women are abused, threatened or slandered on digital social networks.

Gender-based violence is defined by the United Nations as “violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects woman disproportionately.”

This includes physical, sexual or emotional harm. Gender-based cybercrimes include cyber stalking, cyber harassment and cyber bullying. All these offences have been described as avoidance of hate speech, unwanted online messages, making sexual and offensive advances through social networking websites.

This rising tide of misogynist hate and violence is devastating for those who experience it. Yet it is ignored by tech companies and policymakers who continue to place greater value and protections on copyright than they do on human beings and our rights online.

Well, when did digital violence actually take hold in Pakistan? Why did it happen? Who is to be held responsible? Various version of answers to all these questions can be found in numerous stories, such as that of journalists Asma Shirazi and Gharida Farooqi. The question that one must ponder is, when will digital violence stop? Can we stop it? And will anyone muster the courage to make it stop? Is there any redress for a complaint? These are the questions that we all have to work together to answer.

Many months ago, we used to say that there were thousands of similar instances of social media importunity and digital violence in Pakistan, but now out of the millions of exemplifications, it is tough to determine which ones are worth mentioning and which ones are not.

Women journalists in Pakistan continue to face increasing levels of online harassment, including trolling, cyber-bullying, intimidation and doxxing. It is more important than ever that media organization, unions, and other stakeholders work together to spread awareness about the issues faced by media practitioners and support women in the field of journalism, those who face harassment and such type violence.

According to a periodic report by the Economist Intelligence Unit, the rate of online violence against women worldwide is 85%. What’s intriguing about this report is the number of women who reported harassment and threats of violence online from their particular and professional networks. The rate of women who reported being victimized by other women was 65%, while the rate of women who reported particular run ins with online violence was 35%. One thing that this report suggests is that the victims of digital violence are substantially women, who are associated with some profession.

Lately, Pakistan’s famed journalist Gharida Farooqi gave an illustration of the global epidemic of online harassment in The Washington Post. The cost of these incidents of harassment is far lesser in grief and demotion for their victims. The voices of thousands of women intelligencers around the world have been suppressed and, in some cases, excluded entirely. Still, they have to struggle to keep their jobs.

Meanwhile, intelligencer Javeria Siddique, the widow of late journalist Arshad Sharif, also broke her silence through a post about the scornful social media crusade and trolling while she is in the iddah period. According to Javeria, the movement of harassment by political activists and pixies is discipline for standing by her husband. She added, “My husband is no more but I'm alive, but some people want to bury me alive too.”

Like in Pakistan, the question is that when her iddah will end, will Javeria be still an equally responsible person to fulfil her journalistic liabilities as well as domestic chores in this society in the same way when her husband stood by her side?

According to a report by the Economist Intelligence Unit, 78% of women do not have an effective agency to report online harassment. According to the check, 62% of the women are facing passions of helplessness because they’ve veritably many platforms to deal with this problem.

In 2017, journalist Tanzeela Mazhar took a case of online harassment to the courts numerous times crying hoarse for justice. There was a case of harassment against the functionary of the state-owned TV channel PTV, which was successful after numerous times.

Nonetheless, panels of imputations are active, but they are still not sure whether or not they (women) would be able to get justice within the four walls of their institutions. “She was wearied, stalked and hovered with rape and murder," Gharida said in an interview, likening online harassment to digital violence. Her fake prints have surfaced constantly on pornographic websites and social media. Analogous cases of ill-treatment of women journalists are heard each over the world. After all, what is the reason that the victims of digital harassment are women? One of the main reasons for this is lack of justice in Pakistan. A largely complex system of justice doesn’t allow women to knock on the door of justice. Restrictions on women’s movement by family and fear of their family’s response help women from submitting formal complaints as they are forced to visit the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) Office and submit their CNIC number, phone number and father's name. Ubiquitously, they have to meet certain ‘demands’ for getting the needful done.

The digital violence and harassment issues identified in this report are based on actual experiences and examples. Women have been reeling under the effects of online violence for years while trying to find solutions in various ways for peace of mind. It is high time that we ended the campaigns and movements to make women more accessible on digital platforms.

Saddia Mazhar, a journalist from central Punjab, has been mentally ill for the past several years due to digital violence. She said in a telephone interview, her pictures and personal-life information were posted on a fake ID on the social media website Facebook.

On the other hand, Saddia complained to the FIA Office in Islamabad, “the complaint subject was, that I want the IP address of this fake Facebook account so that I can be vigilant and careful of this person in future.” After almost a year, the FIA sent me an email in which it was admitted that they did not have any technology that can find the IP address of a fake Facebook account.

For over a year and a half, Saddia kept asking for help from institutions, and finally, she got information from their friends, she officially reported to Facebook authorities that fake profile. “However, after the complaint, all of my information was deleted from the fake Facebook account within three to four days”.

Albeit all precautions, warnings and repercussions, just a simple piece of advice to all and sundry is that the parents ought to educate and train their children about the ethics of using social media while giving them access to the internet.

Finally, we need robust, tangible and tough laws – of course with strict implementation – with regard to fake and dual accounts used for cyber harassment offenders of any kind against anyone. Along with the legislation to deal with online violence, institutions should also act against criminals. The country's security agencies must be punished befittingly if they fail to curb this heinous crime.

Gender-based violence is defined by the United Nations as “violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects woman disproportionately.”

This includes physical, sexual or emotional harm. Gender-based cybercrimes include cyber stalking, cyber harassment and cyber bullying. All these offences have been described as avoidance of hate speech, unwanted online messages, making sexual and offensive advances through social networking websites.

This rising tide of misogynist hate and violence is devastating for those who experience it. Yet it is ignored by tech companies and policymakers who continue to place greater value and protections on copyright than they do on human beings and our rights online.

Well, when did digital violence actually take hold in Pakistan? Why did it happen? Who is to be held responsible? Various version of answers to all these questions can be found in numerous stories, such as that of journalists Asma Shirazi and Gharida Farooqi. The question that one must ponder is, when will digital violence stop? Can we stop it? And will anyone muster the courage to make it stop? Is there any redress for a complaint? These are the questions that we all have to work together to answer.

Many months ago, we used to say that there were thousands of similar instances of social media importunity and digital violence in Pakistan, but now out of the millions of exemplifications, it is tough to determine which ones are worth mentioning and which ones are not.

Women journalists in Pakistan continue to face increasing levels of online harassment, including trolling, cyber-bullying, intimidation and doxxing. It is more important than ever that media organization, unions, and other stakeholders work together to spread awareness about the issues faced by media practitioners and support women in the field of journalism, those who face harassment and such type violence.

According to a periodic report by the Economist Intelligence Unit, the rate of online violence against women worldwide is 85%. What’s intriguing about this report is the number of women who reported harassment and threats of violence online from their particular and professional networks. The rate of women who reported being victimized by other women was 65%, while the rate of women who reported particular run ins with online violence was 35%. One thing that this report suggests is that the victims of digital violence are substantially women, who are associated with some profession.

Lately, Pakistan’s famed journalist Gharida Farooqi gave an illustration of the global epidemic of online harassment in The Washington Post. The cost of these incidents of harassment is far lesser in grief and demotion for their victims. The voices of thousands of women intelligencers around the world have been suppressed and, in some cases, excluded entirely. Still, they have to struggle to keep their jobs.

Meanwhile, intelligencer Javeria Siddique, the widow of late journalist Arshad Sharif, also broke her silence through a post about the scornful social media crusade and trolling while she is in the iddah period. According to Javeria, the movement of harassment by political activists and pixies is discipline for standing by her husband. She added, “My husband is no more but I'm alive, but some people want to bury me alive too.”

Like in Pakistan, the question is that when her iddah will end, will Javeria be still an equally responsible person to fulfil her journalistic liabilities as well as domestic chores in this society in the same way when her husband stood by her side?

According to a report by the Economist Intelligence Unit, 78% of women do not have an effective agency to report online harassment. According to the check, 62% of the women are facing passions of helplessness because they’ve veritably many platforms to deal with this problem.

In 2017, journalist Tanzeela Mazhar took a case of online harassment to the courts numerous times crying hoarse for justice. There was a case of harassment against the functionary of the state-owned TV channel PTV, which was successful after numerous times.

Nonetheless, panels of imputations are active, but they are still not sure whether or not they (women) would be able to get justice within the four walls of their institutions. “She was wearied, stalked and hovered with rape and murder," Gharida said in an interview, likening online harassment to digital violence. Her fake prints have surfaced constantly on pornographic websites and social media. Analogous cases of ill-treatment of women journalists are heard each over the world. After all, what is the reason that the victims of digital harassment are women? One of the main reasons for this is lack of justice in Pakistan. A largely complex system of justice doesn’t allow women to knock on the door of justice. Restrictions on women’s movement by family and fear of their family’s response help women from submitting formal complaints as they are forced to visit the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) Office and submit their CNIC number, phone number and father's name. Ubiquitously, they have to meet certain ‘demands’ for getting the needful done.

The digital violence and harassment issues identified in this report are based on actual experiences and examples. Women have been reeling under the effects of online violence for years while trying to find solutions in various ways for peace of mind. It is high time that we ended the campaigns and movements to make women more accessible on digital platforms.

Saddia Mazhar, a journalist from central Punjab, has been mentally ill for the past several years due to digital violence. She said in a telephone interview, her pictures and personal-life information were posted on a fake ID on the social media website Facebook.

On the other hand, Saddia complained to the FIA Office in Islamabad, “the complaint subject was, that I want the IP address of this fake Facebook account so that I can be vigilant and careful of this person in future.” After almost a year, the FIA sent me an email in which it was admitted that they did not have any technology that can find the IP address of a fake Facebook account.

For over a year and a half, Saddia kept asking for help from institutions, and finally, she got information from their friends, she officially reported to Facebook authorities that fake profile. “However, after the complaint, all of my information was deleted from the fake Facebook account within three to four days”.

Albeit all precautions, warnings and repercussions, just a simple piece of advice to all and sundry is that the parents ought to educate and train their children about the ethics of using social media while giving them access to the internet.

Finally, we need robust, tangible and tough laws – of course with strict implementation – with regard to fake and dual accounts used for cyber harassment offenders of any kind against anyone. Along with the legislation to deal with online violence, institutions should also act against criminals. The country's security agencies must be punished befittingly if they fail to curb this heinous crime.