Unlike the natural sciences, there is a strong likelihood that the theories and ideas in the social and human sciences are getting ossified, because once the idea becomes a part of existing power relations, it tends to become static. Thus, orthodoxies emerge in the field of knowledge. Today, conceptual orthodoxies are even more pronounced, because we cannot think of an alternate world or society without modern institutions and notions like the nation-state, currency, roads, banking, impersonal institutions, stock exchanges, political parties, elections, and other symbols of modernity. This time bound perspective creates a skewed vision of reality.

However, a longer view of history reveals that there are societies that live without these institutions. Hence, we can say that humans have developed diverse ways for organization and self-organisation within a society in the backdrop of certain power dispensations and historical contexts. James Campbell Scott was one of the pioneering scholars of subaltern groups and politics, and non-state societies who took a long durée of the social practices which were rejected by modern orthodox scholarship as primitive, unruly or backward.

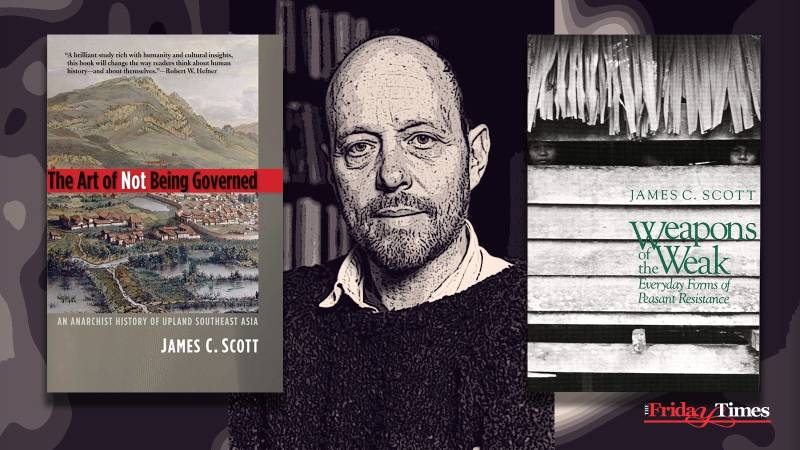

Going against the grain, James Scott carried out pioneering studies to unveil the “the dramaturgy of power” that keeps its hegemony over society, and the existence of resistance to predatory states in the quotidian affairs of life. After living a fruitful scholarly life, James Scott passed away on July 19, 2024. This piece is an attempt to pay homage to his conceptual contributions to the disciplines of political and social sciences.

Born in New Jersey in December 1936, James Scott went on to study political economy in Massachusetts, Burma, and Paris. He earned a Ph.D. in political science from Yale University where he served as a professor of political science and anthropology before retiring in 2021. For his contributions to the social sciences, James Scott received the Benjamin E. Lippincott Award from the American Political Science Association in 2015, the Prize for High Achievement in Political Science for his lifetime accomplishment in 2018 and ASK Social Science Award in 2021.

To elaborate on modes of control, James Scott introduces the idea of ‘transcripts,’ which dictates dominant and the weak to adhere to certain social roles and behavior. He claims that hegemony functions at a subconscious level in internalized forms, rather than explicit and willful acts.

Scott’s contributions to modern scholarship is the introduction of heterogenic concept of “everyday resistance’ to the predatory state. While studying resistance, it is a commonly observed norm in academia to focus on the things that are visible and stand in stark opposition to another. Thus, there is a tendency among scholars to focus on outward manifestations, rather identifying the underlying factors resulting in certain outward behaviour or traits. In James Scott’s conceptual framework, theory is not something that descends into ground from an ivory tower. Rather, it stems from the quotidian affairs of life and society.

To elaborate on modes of control, James Scott introduces the idea of ‘transcripts,’ which dictates dominant and the weak to adhere to certain social roles and behavior. He claims that hegemony functions at a subconscious level in internalized forms, rather than explicit and willful acts. So, internalized hegemony also begets unconscious strategies to resistance. So, it can be said that certain hegemonic practices elicit forms of resistance typical to it. Therefore, there are modes of resistance in society which function in invisible, quiet and disguised forms. Seen in this way, hegemony functions at the subconscious level of agency and sublimates at structural level. James Scott sees resistance somewhere between structure and agency.

Thus, he claims that ‘most of the political life of subordinate groups is to be found neither in the overt collective defiance of powerholders, nor in complete hegemonic compliance, but in the vast territory between these two opposites.’ It is this vast realm of political action that has been often overlooked by political scientists. James Scott has discovered a new continent of resistance that exists between the two seas of agency and structure. Through his research in Zambia, Scott proved that historically, most human beings lived outside state control “under loose-knit empires or in situations of fragmented sovereignty.” This space is ignored because it does not form collective action and therefore is not considered politics in the dominant discourses in the political and social sciences in Western academia.

The everyday strategies and subterranean forms of resistance enable people to avoid being governed by predatory power. The strategies and arsenals of resistance employed by common people are prosaic in nature. This enables people to “struggle below the radar” of the state. To explicate the art of resistance to the domination of the state in mundane spaces and practices, James Scott deploys the idea of carnivalesque, propounded by the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin in his study of a famous French novel ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’ in his book ‘Rabelais and His World’.

For Bakhtin, the carnival is a sanctioned location and permitted revelry in which uninhibited speech occurs, roles get reversed - buffoons become kings, and kings become buffoons; the rigid order of the world is thrown off, and inversion of power relationships are celebrated. Through these acts in the carnival, power relationships are suspended and thus people upset power through imagery. Scott extrapolates the concept of carnivalesque from literature into the study of society and politics. “From the lower classes,” writes James Scott, “who spent much of their lives under the tension created by subordination and surveillance, the carnivalesque was a realm of release.” Hence, the carnival become a space for resistance and freedom.

The famous Punjabi folk song Lagi Bina invites lovers to the carnival - Chal Mele Nu Chaliye. Here it speaks of moments of merry and emancipation from the tight grip social norms and fetters of religious orthodoxies in the space of carnival. Similarly, James Scott’s book “Two Cheers for Anarchism,” celebrates common sense, common rule-breaking gestures like jaywalking and rowdy behaviour. It is reminiscent of what characters do in the mela and carnival in South Asian social settings.

For subjective reasons, his book ‘The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia’ holds special appeal for me. This book examines the culture and history of groups inhabiting certain hilly areas in Southeast Asia. It is a sparsely populated area with diverse communities spread over seven countries - Burma, Cambodia, China, India, Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand. The area is named Zomia. Today, we cannot imagine a life without a state informing the structures of society and economy. That is why we focus more on being ruled. The region of Zomia has remained stateless for centuries. Contrary to the prevalent tendency to see the state or government as an indispensable institution of society, Scott, in his study of the Zomia region, shows how people have deliberately and reactively remained stateless for centuries by employing strategies embedded in everyday activities.

These strategies to be ungoverned were adopted to avoid the encroachment of state power from the lowlands into the upland societies of Zomia. In the process, they intentionally avoided state-like structures, practices, or anything that smacks of state intrusion. For example, the people in Zomia “forget” writing as an act of defiance. With such defiant gestures, they formed a society and culture that was antithetical to state at its core. Unlike the state that tries to co-opt societies with distinctive identities within its monolithic structure, the people inhabiting the Zomia region distanced themselves from it through culturally embedded practices.

Although Scott was criticized for generalization and creating academic fiction like Shangri La and Xanadu in his works, his thesis of everyday resistance still provides rich epistemological insights into everyday history. The subterranean social practices and techniques developed by people to not being ruled point toward the formation of underlying tectonic plates. Any shift in these tectonic plates shake the visible structures situated on the upper crust of political in the state. Scott rejects the state narrative of backwardness, rebellion, barbarians, unorganized, stateless, and different epithets to define societies in the fringes as state strategies to bring such group under the ambit of the government.

The most appealing aspect of James Scott’s scholarship is his selection of evocative words to describe amorphous social and political processes. His analytical lexicon contains concepts that have become mainstream conceptual tools to explain certain political and sociological phenomena. Concepts like tactical wisdom, moral economy, acephalous “jellyfish” political structures, swidden agriculture, friction of capital, friction of terrain, weapons of the weak etc., shed light on unexplored sociological facts.

To elaborate his argument, Scott tends to take prosaic examples that normally stand before everyone’s eyes, but escape our attention. For example, roads appear to be an integral part of our existence in modern time, but their existence is enmeshed with broader power strategies and meanings, as roads are the best avenue for the state to project its power and domination. Once we start examining roads through this angle, the meaning, and manifestations of the whole discourse around roads and development takes a different turn. Once its new meaning is accepted, the road - instead of appearing as the hallmark of modernity - stands as a testament to the physical manifestation of state power on physical topography and human geography.

Scott seems to be aware of importance of conceptual instruments - words - in the formulation of our approach and explanations. James Scott’s selection of the titles for his books bespeaks of his unconventional way of approaching analysis and a flair for words to represent certain conditions of society or actions. Some of the titles of his books are: Weapons of the Weak, Decoding Subaltern Politics Ideology, Disguise, Resistance in Agrarian Politics, Domination and the Arts of Resistance, Seeing Like a State, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts and Against the Grain. The presence of art in most of his titles reveals that James does not treat politics as a science. On the contrary, he treats it as an art. That is why the titles are more evocative of art than a science of resistance.

His book “Seeing Like a State” is a critique of the creed of scientism followed by the planners in their administrative ordering of nature and society in the erstwhile Soviet Union and other parts of the world. It is this scientism that infused the hubris of scientific omniscience in the planners who embarked upon social engineering projects at the expense of local realities and knowledges. It is a strange irony of human history that emancipatory ideologies ultimately turn into cages for people when states prefer ideological structures over the agency of the masses. The former USSR is a case in point. To avoid the negative repercussions of an omniscient and omnipotent state, James Scott appears to favour local knowledges and strategies in running the affairs of society.

His book “Seeing Like a State” is a critique of the creed of scientism followed by the planners in their administrative ordering of nature and society in the erstwhile Soviet Union and other parts of the world. It is this scientism that infused the hubris of scientific omniscience in the planners who embarked upon social engineering projects at the expense of local realities and knowledges.

Expanding the boundaries of knowledge is possible in a society where research and thinking take place. A society that blindly follows the certainties of its received knowledge is condemned to repeat the tried and tested ways of seeing and thinking. James C. Scott challenged the habits of seeing the reality of our existence from a statist point of view. Instead, he gave us an alternate perspective to view the disorder of order from within. Though he has left the world, his ideas will keep illuminating the hearts and minds of those who seek knowledge.

A great mind teaches us how to get rid of opinion and build analytical capacity to see beyond the apparent. But in the age of communications and information, in Pakistan, to quote the words of James Scott, the “descriptions and analyses of open political action dominate accounts of political conflict.” That is why 240 million people in Pakistan are dependent on the analysis of a few dozen anchors, commentators, and a few hundred YouTubers and influencers who wallow in the current affairs drivel and engage in hair splitting argumentation on what appears before them. Since they lack the scholarly capabilities to peel off the layers of reality to see the vast realm that exists beneath the appearance, they settled for what is apparent. Thus, we are condemned to lead our life on the basis of the opinions of others, not on knowledge.

There is no denying the fact that similar processes are underway in other parts of the world. However, the difference is that along with all the nonsense of the mainstream and social media, the academic institutions in the West still produce knowledge and ideas in different disciplines. James C. Scott has left us a rich tapestry knowledge for posterity. In Pakistan, we will bequeath trillions of gigabytes of opinions and irrationality on social media and videos to our next generation. We become what we consume. Today, we consume cyber junk in Pakistan. The destiny of such products will be cyber junk, not the domain of knowledge and ideas. The work of scholars like James C. Scott might yet save us from heading into the dustbin of history and knowledge.