It has been almost a year and things at the political and economic front still remain volatile. While two provincial assemblies have been dissolved, the IMF programme is still not revived but it seems that the government, having exhausted all its option, has finally succumbed to the global lender’s demands.

Monetary tightening alongside administrative measures have provided some relief in the form of a steep decline in current account deficit. Yet, the relief is temporary as a major drain on the foreign reserves from mounting debt payments is likely to keep the country’s financial managers on their toes.

Pakistan has more than 70 billion in repayment commitments over the course of next three fiscal years (including 2023). The financing arrangements sought by the government will only help the country see through till March 2024.

(Read more about it: Pakistan’s Short-Term Financing Gap Likely To Be ‘Sorted’ If IMF Deal Goes Through.)

Therefore, to mitigate the situation and buy some time to implement “real” economic reforms, the government should consider restructuring its debt. What makes restructuring even more imminent is the fact that the “freebies” from friendly countries which Pakistan is addicted to, are soon going to dry up.

The Saudi Finance Minister in his recent address at the World Economic Forum stated that the kingdom would now be more cautious while extending debt support to developing countries and would seek economic reforms in the recipient nation for a sustainable debt profile.

Pakistan already had a chance in the shape of Debt Service Suspension Initiatives (DSSI) (a moratorium on debt repayments) during the pandemic but failed to capitalise on it. Thus, some serious deliberation would be required this time around to achieve any meaningful outcomes subsequent to a debt restructuring.

“Policymakers can choose to approach creditors and initiate a debt restructuring process. This will again come at the expense of meeting additional conditionalities agreed with the creditors, who will bear the cost of restructuring. None of these options are without economic pain, but a well-managed restructuring process can allow the economy to recover sooner than later,” proposed the Economic Advisory Group.

However, it is worth analysing that how could a possible restructuring shape up and the global frameworks available to facilitate that process.

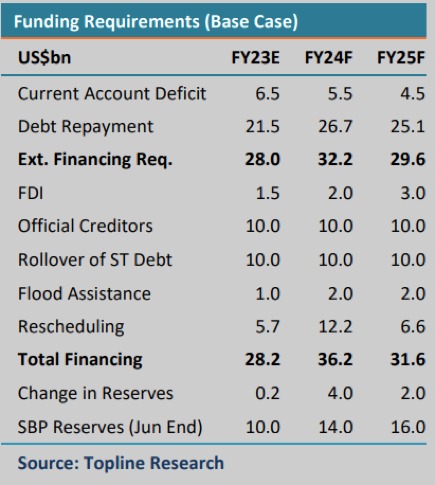

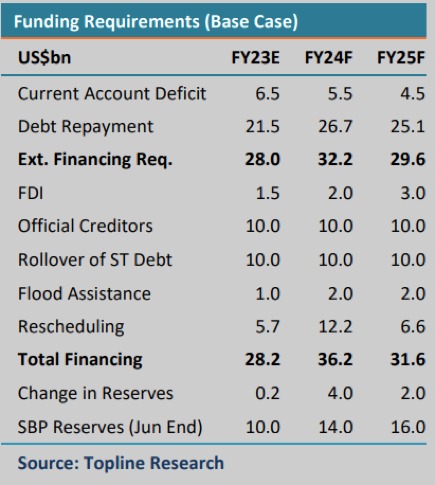

As per a report by Topline Securities, “Considering this external debt repayment crisis, we think Pakistan will do a Debt Rescheduling (Base Case) with its bi-lateral lenders especially China as it forms 30% of government external debt and the repayment to China is huge in next few years. Pakistan must capitalize on its friendly relationship with China and must seek IMF led Debt Restructuring of at least US$30bn for next 3-5years.”

“Other than bilateral/commercial creditors, the government should approach multilaterals to get as much relief as possible. Based on equal treatment, Eurobond maturities falling in next 3-4 years needs to be revisited,” the report further added.

To achieve that Pakistan would need to rely on highly flawed and outdated global frameworks governing the process.

“Today’s approach to debt workouts was devised during the emerging market debt crises of the late 20th century, when creditors were largely western governments and commercial banks. Since then, however, China, India and Saudi Arabia have become increasingly important players in financing poorer countries. The banks involved in the past, meanwhile, have been replaced by thousands of bondholders,” World Bank chief economist, Indermit Gill, said in an interview with the Financial Times.

The World Bank officials have also been critical about the prevailing frameworks of sovereign debt restructuring. Stating that all creditors (of a country) should be compelled by law to cooperate in good faith in sovereign-debt restructurings. What it means is that sovereign debt providers, when their debtors are facing financial difficulties should engage in a collective manner rather than going on a litigious streak to exploit debtors' conditions.

As per a paper published in 2021 by Lee C. Buchheit and Mitu Gulati, Sovereign Debt Restructuring, “If reliance on an implied duty on the part of creditors to participate in collective sovereign debt workouts is thought to be insufficient, sovereigns could consider including an explicit provision in their external debt instruments confirming what we believe most institutional investors already understand and expect — that in the event of severe sovereign distress all similarly situated creditors will be expected to participate in a collective workout process that satisfies certain conditions.”

The World Bank economists also opined, “All sovereign debt contracts should limit how much a creditor can collect through lawsuits outside the Common Framework and, in addition, include ‘Collective Action Clauses’ (CAC) which mean all bonds can be restructured as long as the vast majority of bondholders have agreed. That in turn would clip the wings of so-called vulture funds that try to hold out and then take governments to court to score a bigger payout for themselves.”

This suggestion holds true for Pakistan. “To my knowledge, Pakistan does not have any CAC’s in its agreements. So, the wriggling room on that front is extremely limited,” says, Shahram Azhar, Assistant Professor of Economics at the Bucknell University.

Not having such cover makes a country vulnerable to acts of opportunistic creditors. Case in point, Argentina, which faced multiple lawsuits from hedge funds it owed money to and the nation ended up paying much more than the debt’s actual value.

Last time Pakistan undertook a major restructuring was in the aftermath of 1998 nuclear tests which led to the country being heavily sanctioned. “Post the 9/11 attacks, Pakistan turned from a pariah nation to a major ally to the United States. That aided 3 debt restructurings agreements – the first two rescheduling arrears and payments, while a third provided a debt stock reduction in November 2001,” writes Raza Agha, in an article for the Profit

Experts believe that the preferable avenue for Pakistan to negotiate debt rescheduling is through the IMF and World Bank, which will conduct a debt sustainability analysis to quantify the magnitude of the problem before initiating the formal restructuring process.

As per an article in the Financial Times, “Standard procedures for debt workouts involve the IMF and World Bank conducting a debt sustainability analysis to assess the scale of the problem, before calculating the amount of debt relief needed to restore sustainability and put the debtor on a path to economic growth. Creditor governments then agree how much relief they will provide — a step which typically unlocks an IMF bailout. The process ends when the debtor government is tasked with securing the same terms from its commercial creditors as those offered to the official sector.”

Shahram Azhar is of the opinion, “Pakistan’s ability to restructure right now is extremely limited, primarily because we have lost the trust of creditors. During Imran Khan’s regime, Pakistan reneged on its own promise with the IMF of maintaining the budget its own parliament approved; Pakistan has lost credibility in the eyes of major creditors so it is becoming incredibly difficult (especially given the global recessionary environment) for the country to secure a better deal now.”

However, similar to what is transpiring in Sri Lanka, restructuring would, in any case, be a laborious task and Pakistan highly depends on guarantees from friendly countries for a smooth execution of the process, if initiated.

Monetary tightening alongside administrative measures have provided some relief in the form of a steep decline in current account deficit. Yet, the relief is temporary as a major drain on the foreign reserves from mounting debt payments is likely to keep the country’s financial managers on their toes.

Pakistan has more than 70 billion in repayment commitments over the course of next three fiscal years (including 2023). The financing arrangements sought by the government will only help the country see through till March 2024.

(Read more about it: Pakistan’s Short-Term Financing Gap Likely To Be ‘Sorted’ If IMF Deal Goes Through.)

Therefore, to mitigate the situation and buy some time to implement “real” economic reforms, the government should consider restructuring its debt. What makes restructuring even more imminent is the fact that the “freebies” from friendly countries which Pakistan is addicted to, are soon going to dry up.

Pakistan has more than 70 billion in repayment commitments over the course of next three fiscal years (including 2023). The financing arrangements sought by the government will only help the country see through till March 2024.

The Saudi Finance Minister in his recent address at the World Economic Forum stated that the kingdom would now be more cautious while extending debt support to developing countries and would seek economic reforms in the recipient nation for a sustainable debt profile.

Pakistan already had a chance in the shape of Debt Service Suspension Initiatives (DSSI) (a moratorium on debt repayments) during the pandemic but failed to capitalise on it. Thus, some serious deliberation would be required this time around to achieve any meaningful outcomes subsequent to a debt restructuring.

“Policymakers can choose to approach creditors and initiate a debt restructuring process. This will again come at the expense of meeting additional conditionalities agreed with the creditors, who will bear the cost of restructuring. None of these options are without economic pain, but a well-managed restructuring process can allow the economy to recover sooner than later,” proposed the Economic Advisory Group.

However, it is worth analysing that how could a possible restructuring shape up and the global frameworks available to facilitate that process.

As per a report by Topline Securities, “Considering this external debt repayment crisis, we think Pakistan will do a Debt Rescheduling (Base Case) with its bi-lateral lenders especially China as it forms 30% of government external debt and the repayment to China is huge in next few years. Pakistan must capitalize on its friendly relationship with China and must seek IMF led Debt Restructuring of at least US$30bn for next 3-5years.”

“Other than bilateral/commercial creditors, the government should approach multilaterals to get as much relief as possible. Based on equal treatment, Eurobond maturities falling in next 3-4 years needs to be revisited,” the report further added.

To achieve that Pakistan would need to rely on highly flawed and outdated global frameworks governing the process.

“Today’s approach to debt workouts was devised during the emerging market debt crises of the late 20th century, when creditors were largely western governments and commercial banks. Since then, however, China, India and Saudi Arabia have become increasingly important players in financing poorer countries. The banks involved in the past, meanwhile, have been replaced by thousands of bondholders,” World Bank chief economist, Indermit Gill, said in an interview with the Financial Times.

The World Bank officials have also been critical about the prevailing frameworks of sovereign debt restructuring. Stating that all creditors (of a country) should be compelled by law to cooperate in good faith in sovereign-debt restructurings. What it means is that sovereign debt providers, when their debtors are facing financial difficulties should engage in a collective manner rather than going on a litigious streak to exploit debtors' conditions.

As per a paper published in 2021 by Lee C. Buchheit and Mitu Gulati, Sovereign Debt Restructuring, “If reliance on an implied duty on the part of creditors to participate in collective sovereign debt workouts is thought to be insufficient, sovereigns could consider including an explicit provision in their external debt instruments confirming what we believe most institutional investors already understand and expect — that in the event of severe sovereign distress all similarly situated creditors will be expected to participate in a collective workout process that satisfies certain conditions.”

The World Bank economists also opined, “All sovereign debt contracts should limit how much a creditor can collect through lawsuits outside the Common Framework and, in addition, include ‘Collective Action Clauses’ (CAC) which mean all bonds can be restructured as long as the vast majority of bondholders have agreed. That in turn would clip the wings of so-called vulture funds that try to hold out and then take governments to court to score a bigger payout for themselves.”

Similar to what is transpiring in Sri Lanka, restructuring would, in any case, be a laborious task and Pakistan highly depends on guarantees from friendly countries for a smooth execution of the process, if initiated.

This suggestion holds true for Pakistan. “To my knowledge, Pakistan does not have any CAC’s in its agreements. So, the wriggling room on that front is extremely limited,” says, Shahram Azhar, Assistant Professor of Economics at the Bucknell University.

Not having such cover makes a country vulnerable to acts of opportunistic creditors. Case in point, Argentina, which faced multiple lawsuits from hedge funds it owed money to and the nation ended up paying much more than the debt’s actual value.

Last time Pakistan undertook a major restructuring was in the aftermath of 1998 nuclear tests which led to the country being heavily sanctioned. “Post the 9/11 attacks, Pakistan turned from a pariah nation to a major ally to the United States. That aided 3 debt restructurings agreements – the first two rescheduling arrears and payments, while a third provided a debt stock reduction in November 2001,” writes Raza Agha, in an article for the Profit

Experts believe that the preferable avenue for Pakistan to negotiate debt rescheduling is through the IMF and World Bank, which will conduct a debt sustainability analysis to quantify the magnitude of the problem before initiating the formal restructuring process.

As per an article in the Financial Times, “Standard procedures for debt workouts involve the IMF and World Bank conducting a debt sustainability analysis to assess the scale of the problem, before calculating the amount of debt relief needed to restore sustainability and put the debtor on a path to economic growth. Creditor governments then agree how much relief they will provide — a step which typically unlocks an IMF bailout. The process ends when the debtor government is tasked with securing the same terms from its commercial creditors as those offered to the official sector.”

Shahram Azhar is of the opinion, “Pakistan’s ability to restructure right now is extremely limited, primarily because we have lost the trust of creditors. During Imran Khan’s regime, Pakistan reneged on its own promise with the IMF of maintaining the budget its own parliament approved; Pakistan has lost credibility in the eyes of major creditors so it is becoming incredibly difficult (especially given the global recessionary environment) for the country to secure a better deal now.”

However, similar to what is transpiring in Sri Lanka, restructuring would, in any case, be a laborious task and Pakistan highly depends on guarantees from friendly countries for a smooth execution of the process, if initiated.