A book by Denise Hearn and Vass Bednar is the latest from McGill Max Bell Lectures. It has received attention from a wide array of citizens including economists, government officials and independent business representatives, all of whom share concerns on stifled competition and innovation in Canada.

Hearn and Bednar express concerns on corporate power and concentration by alluding to “three major telecommunications companies, five grocers, a few big banks, [and] two major airlines.” This phenomenon is problematic not just because of rising grocery bills and weak bargaining position for workers, but also because of concerns about long-term economic growth, less research and development (R&D) and low productivity. What this means is that citizens both on the left and the right can stand united against such market concentration, given their concerns about worker rights and economic growth respectively.

Hearn and Bednar elaborate that the dominance of mega firms in the digital age relies on unmatched access to big data, coding talent and computing power

Hearn and Bednar refer to financialisation, where the predominant concern is on maximising shareholder returns, that comes at the expense of other stakeholders including consumers, workers and suppliers. They also emphasise that markets are “public creations” and should be “democratically determined” lest they are shaped by private corporate interests. Both points about the skewed objective of the firm and the political contours of the market are reminiscent of the arguments made by Cambridge economist Ha Joon Chang in his popular books 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism (2010) and Edible Economics (2022).

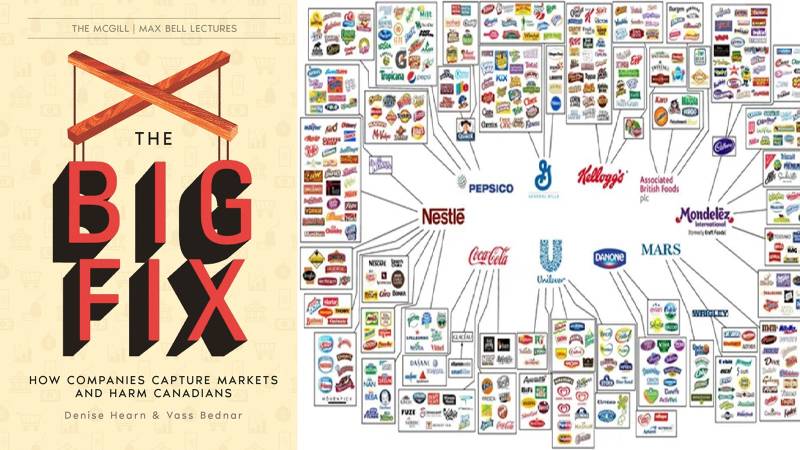

The authors highlight the illusion of competition by arguing that many brands are bought by the same parent company such as Loblaws (NoFrills, Real Canadian Superstore, Shoppers Drugmart, T&T). The authors generally term the approach of buying out as many companies as possible as “lazy growth” – that comes at the expense of investing in R&D or employee training. Thus, they go against the Schumpeterian grain by stating that large incumbent companies have little incentive to innovate and compete, as they can simply co-opt the innovation of competitors based on their monopoly profits.

Hearn and Bednar argue that such market concentration allows big firms to legitimise price hikes and increased profit margins under the cover of “supply chain bottlenecks”. They allude to research that increased profits replaced labour costs as the “main driver of price increases” and which explain about 40% of inflation. A similar argument has been made by Nick Romeo in his book The Alternative (2023) where he states that “corporate profiteering” has been responsible for “more than half of the price increases in the nonfinancial corporate sector” in the US.

The authors mention that independent businesses in the digital age find themselves at the mercy of dominant firms like Google, Amazon and Microsoft, as they are dependent on the latter for platforms including advertising and cloud storage. Hearn and Bednar elaborate that the dominance of such incumbent firms rests on unmatched access to big data, coding talent and computing power. Thus, they reiterate that big firms which “gobble up” small start-up companies contribute towards “Canada’s productivity crisis” and stagnant growth.

In discussing solutions to the market concentration problem, the authors state that competition policy in Canada was shaped by neoliberalism as promoted by Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s. Additionally, they argue that under the garb of “mathematical rigour,” neoclassical economics has led to the “undemocratic decision” to focus on efficiency and free markets. However, like Ha-Joon Chang, they argue that free markets have meant freedom for large firms but not for “workers, consumers, and independent businesses.”

Hearn and Bednar caution that instead of government bureaucracy and the large role of economists and lawyers, all of whom are susceptible to corporate power, the issue of Canada’s market concentration problems should be addressed through democratic citizen assemblies based on “diverse perspectives” from citizens. This is reminiscent of Suleyman and Bhaskar in their book The Coming Wave (2023) where they argue for citizen assemblies to play their role in the formulation of policy pertaining to emerging challenges from AI and automation. Likewise, French economist Thomas Piketty has argued in his book Time for Socialism (2021) for a form of democratic or participatory socialism.

The authors conclude by stating that we need to “create an economy that works for everyone”, which is consonant with Canadian economist Jim Stanford’s approach in Economics for Everyone (2015). Overall, the message of the book by Hearn and Bednar can be situated in the milieu of various other books, which seem to converge against corporate power, worker disenfranchisement, neoclassical economics and, in general, economic inequality.