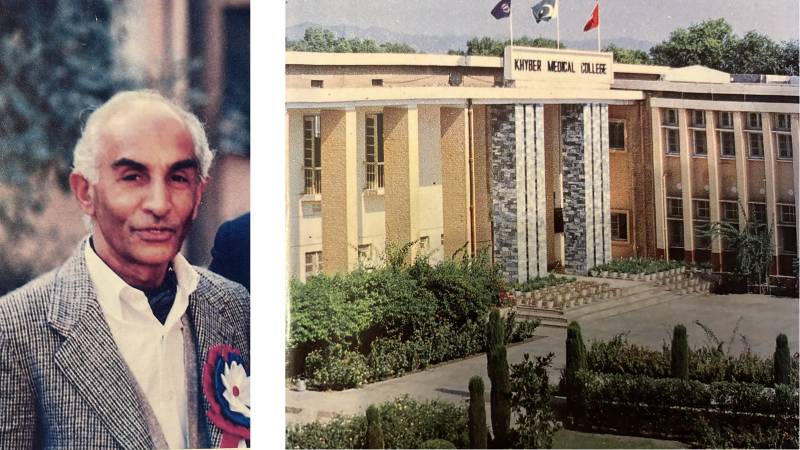

He was diminutive in stature but was of great design. I had been acquainted with this remarkable in various capacities since 1958.

Dr Nasir Uddin Azam Khan, a great physician, superb teacher, administrator and humanitarian, died recently at age 96 in Peshawar. It is hard to draw a circle around the life of a giant. But try I must for I knew him from myriad different angles: teacher, mentor, confidant and (dare I claim) a friend.

He was born into a well to do family in Abbottabad. A child prodigy, he was always ahead of his peers. He attended college in Rawalpindi because, to his loving mother, Rawalpindi was closer to Abbottabad than Peshawar - where he was planning to attend Islamia College.

He got into King Edward Medical College Lahore on reserved seats for the then North West Frontier Province (NWFP). He always felt that quota and reserved seats meant getting into college on grounds other than merit. But securing first position in the first professional examination at the end of the second year gave him renewed confidence that he could successfully compete with the best. There was no looking back.

After graduating with distinction from King Edward Medical College, he was posted in Miran Shah in North Wazirstan, where he spent three years. That stay in Miran Shah came to an abrupt halt when the provincial government selected him for postgraduate education and training in Great Britain.

From all accounts, he succeeded in Great Britain, getting membership in the Royal Colleges of both England and Edinburgh.

Upon his return to Peshawar in the early 1950s, he was appointed medical officer in charge of medical outpatient in Lady Reading Hospital. Subsequently, he was given a ward and the status of a medical consultant.

Khyber Medical College had started in 1955, and within two years, in 1957, the College needed clinical facilities for its students. The provincial government designated Lady Reading Hospital, that had the status of a district hospital, as a teaching hospital.

The specialists working in Lady Reading were appointed to faculty positions in the college. Both internal medicine specialists Dr Ali Raza and Dr Nasir Azam Khan were appointed associate professors in the department of medicine in the College. Since there was no qualified teacher in pharmacology at the time, Dr Nasir was given the additional charge as chairman of the department. As a third-year medical student in 1959, that was my first introduction to Dr Nasir.

He was a superb teacher. He was always impeccably dressed, eloquent, and articulate. His lectures were full of rhetorical flourishes and historic vignettes. That made an otherwise boring subject of drugs, their chemical formulae and their effects on the body interesting and even enjoyable. And he was never on time.

He would be late as much as 30-minutes for an hour-long class. He would rush in the classroom, start the lecture and sometimes would go over the allotted time. That meant the class would miss the ride on the college buses that took students to Lady Reading Hospital 9 miles away in the city for clinical training. I know that the principal Fida Muhammad Khan talked to him, but to no avail.

There was a preacher from Peshawar City by the name of Sethi Abdul Ghafoor, who would make rounds of every school and college, enter a classroom, preach for a minute or two and then be on his way to another classroom. In one week, he would complete the rounds of all primary and high schools and colleges in Peshawar. He would refuse a ride and walk from school to school and college to college. Every professor and government official had seen the man with salt-and-pepper beard, not-too-clean clothes, dirt-crusted shoes and a long staff. Most teachers and government officials, if they had studied in Peshawar, were familiar with Sethi Sahib. Dr Nasir was not.

Once, Dr Nasir was in the middle of delivering a pharmacology lecture when Sethi Sahib barged in. It was startling for the new professor, who did not tolerate any interruptions. He looked at the strange man and ordered him to get out. Sethi Sahib had been doing his preaching for decades, and he never paid attention to the teachers. Teachers, on the other hand, would stand silent until the man left, and would then restart the lecture.

In anger and frustration, Dr Nasir summoned the peon sitting outside the classroom and ordered him to remove the man. The peon stood silent. Sethi Sahib finished his one-minute soliloquy and left, leaving the young professor confused, frustrated and helpless. He dismissed the class and went to principal’s office to lodge a complaint. When he was told about the man and his mission, and that there were no doors in educational institutions and government offices that were closed to him, the young professor calmed down.

Unlike his tardiness for pharmacology lectures, he was always on time for ward rounds and lectures on clinical medicine at the hospital. On his unit, ward rounds were very formal. Accompanied by his entourage of junior teachers, nurses and medical students, he would set the pace, stop at each bed, listen to patient history, results of laboratory investigations and the treatment. He would change the treatment if needed, and would examine the patient if warranted. He had faith in his staff.

Dr Nasir was a deeply religious man. He believed in the superiority of Islam over all other faiths. Though he did not preach that concept overtly, sometimes his deep convictions would come through.

From 1983 to 1988, he served as principal of Khyber Medical College. His reign was remarkable for infusing discipline in the college and the building of a new block to house the department of jurisprudence. Academic standards also improved. His tenure was also remarkable for facilitating the publication of the first comprehensive history of the college.

While he was practicing, he had an arrangement with a pharmacy owner by the name of Iqbal. Whenever Dr Nasir saw a patient who could not afford the prescribed medicines, the patient was directed to Iqbal

I have always been a student of history. I am interested in understanding the evolution of institutions. Whereas in the West there is considerable interest in preserving the history of institutions, in India and Pakistan there is great paucity in finding coherent accounts of great institutions. I approached Dr Nasir and asked if he would be interested in having a written history of Khyber Medical College. He was enthusiastic. He laid open the archives and records of the college to a history scholar from the University of Peshawar. After two years, a definitive history of Khyber Medical College and its allied Institutions was published in 1993.

Dr Nasir taught diseases with historic context. For example, while teaching smallpox, he would paint a picture of an English country physician by the name of Edward Jenner in the mid-18th century, who overheard two milkmaids, his employees, telling each other that since one of them had already contracted cowpox, she is now protected against smallpox. This cross immunity between the two diseases was not known. That eavesdropping by Jenner lead to the development of a smallpox vaccine. How could one not think of smallpox and not think about a country physician eavesdropping on the conversation between two milkmaids?

I immensely enjoyed his lectures and the historic contexts. In my case, that interest led to my appointment as professor of medical humanities at the University of Toledo. I wrote to him and told him that this would have never happened had he not sparked my interest in the field of medical humanities.

One winter night in 1991, I woke up with chest discomfort. I tried to figure out the cause of pain, but nothing made sense. As the pain increased in intensity and gripped my left arm and jaw, I found myself sitting in Dr Nasir’s lecture 30 years earlier as a student and heard his clear and crisp voice telling the class that the sudden onset of severe chest pain with radiation to the arm and jaw is the characteristic of a heart attack.

Did I mention earlier that he was a great teacher?

In 1963, when I boarded Alitalia Aeroplan for my journey to the USA, I was apprehensive and restless. I was fearful of the unknown combined with anxiety about staying grounded in my faith and culture. The avant garde culture of the United States, as depicted in Hollywood movies, was strange and alien to me. Somewhere over the Atlantic, I wrote to him and asked his advice. After all, he had spent many years in England and had returned unscathed. I received his answer a few weeks later.

It was a very cordial letter in which he said that the circle of briefs in Islam is wide. It is incumbent upon the followers to enjoy their lives to the fullest within the constraints prescribed by religion.

I have followed his advice, but at times the cliché, “It is much easier to ask for forgiveness than to resist the temptation” was a handy excuse for occasional excursion outside the circle.

While he was practicing, he had an arrangement with a pharmacy owner by the name of Iqbal. Whenever Dr Nasir saw a patient who could not afford the prescribed medicines, the patient was directed to Iqbal, from whom he got free medications. At the end of the month, Dr Nasir would pay the total amount to Iqbal. This was all done quietly and no one except Dr Nasir’s ward staff knew of this arrangement.

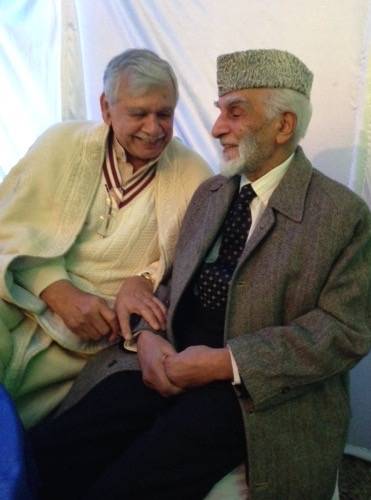

In the initial decades of his practice, he was very strict and unbending. In later decades, he mellowed a lot. He always called me by my first name, but for 15-20 years I noticed a change. He would address me as "putr," meaning son in Hindko.

During my annual visits to Peshawar, I made sure I visited him at his home. Over a cup of tea, we would talk about many things. His knowledge of religion and his life experiences were always amazing. When he was able, he would always come to attend my lectures at the medical college and Peshawar Museum. It was intimidating as well as heartwarming that a giant of a man who moulded my persona in so many ways would make an effort to listen to one of his students.

حق مغفرت کرے عجب آزاد مرد تھا