Alexander the Great headed from Egypt to Syria and finally reached Mesopotamia. After the failure of negotiations between Alexander and King Darius III, the Macedonians planned a decisive attack. The Battle of Gaugamela (Arbela) took place on 1 October 331 BC against the Persian army under Darius III. This fighting took place in Gaugamela, a village on the banks of the River Bumodus, north of Arbela, modern-day Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan. The size of the Macedonian army was 47,000 while the Persian strength is estimated around 50,000 to 120,000. The number of casualties and losses are estimated at 1,100 to 1,500 Greeks and 40,000 to 90,000 Persians.

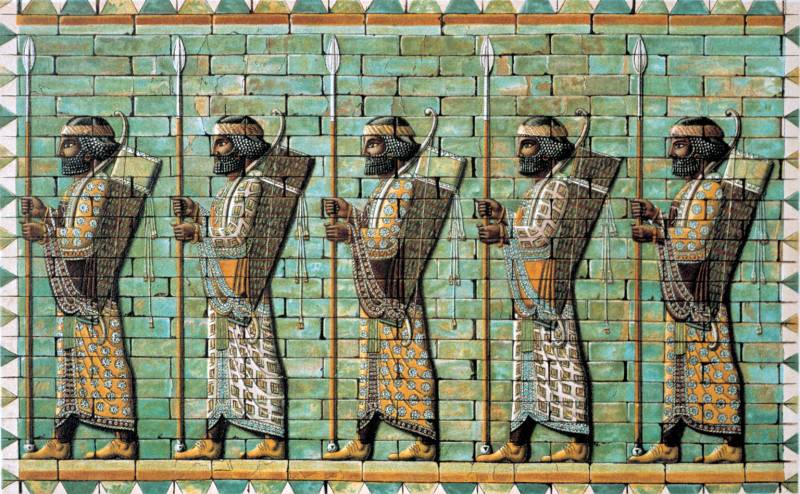

Darius III managed to escape on horseback. The Bactrian cavalry and Bessus caught up with him. The Persian King planned to head further east for raising another army to face Alexander. At the same time, he dispatched letters to his eastern satraps asking them to remain loyal to the Achaemenids. But Bessus murdered Darius before fleeing eastwards, which saddened Alexander. Bessus proclaimed himself as king of the Persian satrapy of Bactria. He continuously resisted Alexander’s forces. After a short rule in Bactria, he fled into Sogdiana, where he was arrested by his own officers, who handed him over naked and bound to Alexander, who had him executed at Ecbatana, the capital of the Median kingdom. The execution was supervised by Darius III’s brother Oxyathres. The Persians cut off his ears and nose, which was the Persian way of punishment. King Darius III had three children: Staterira, Drypetis and Ochus. Besides Roxana, Alexander married Stateira, at Susa in 324 BC

Alexander invaded modern-day Afghanistan in 330 BC as part of the war against Persia. He wanted to expand his control over Persia and its vast boundaries in the east. Having secured the victory over Bactria and Sogdiana, he captured Kapisa in 327 BC. He then passed through a region called Nikaea, a site close to modern Kabul, and reached the fertile land of what is today Nangarhar or Jalalabad.

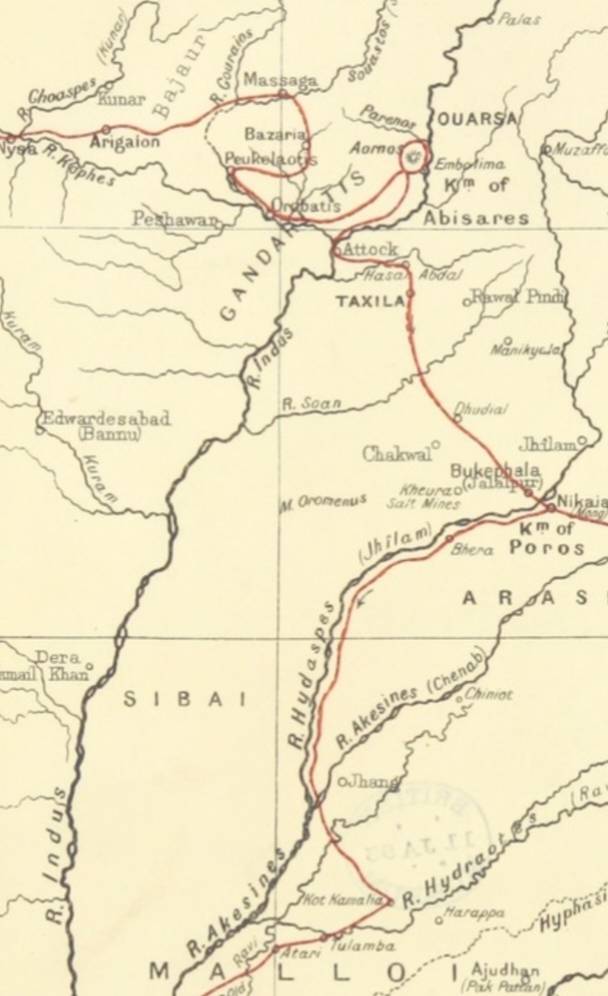

After offering a sacrifice to the goddess Athena, Alexander divided his forces there to invade the Gandhara satrapy in the Indus Valley. Alexander entered in the Valley of the Indus through the Hindukush mountain range via Khyber Pass, Dir or Bajaur, Kunar, Chitral and Swat regions. After fighting many battles with local tribes, including Assakenois (Assacenians), he finally reached the Chakdara plains. Alexander had taken scientific staff with him to explore India. There was Callisthenes (a historian), Onesicritus (a geographer), Anaxarchus (a philosopher) and various botanists and zoologists. It is supposed that this scientific mission was prompted by Alexander’s old teacher Aristotle.

A number of ancient cities, mountains and rivers are attested to in the Indus Valley Region (today located in Pakistan), attested to during Alexander’s Campaign in modern-day Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Alexander captures Nysa

Arrian mentions the city of Nysa between the Cophen (Kabul) and Indus Rivers.

Alexander found in Gandhara a city called Nysa, which was said to be founded by Dionysus after the conquest of India. Dionysus named this place Nysa in the honour of his nurse. This god is also known as the god of theatre, the masked god or the wine god. Many Greek stories believe Dionysus was a son of Zeus. It is told that Queen Hera was angry with Zeus for having this child, and so Zeus gave Dionysus to Nysa, a nursemaid. She was said to be buried at the town of Scythopolis in Syria.

In Greek mythology, the mountainous district of Nysa is variously associated with Macedonia, Boeotia (Greece), Thrace (Southeast Europe), Cilicia (Anatolia), Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, Syria, Babylonia, Arabia or India. Stephanos of Byzantium, a grammarian and author of 6th Century A.D., names 10 cities with the name Nysa, Some of which are real (Nysa on the Meander) and others are mythical. According to Sir William Jones, Meros is said by the Greeks to have been a mountain in India, on which their Dionysus was born, and that Meru is also a mountain near the city of Naishada or Nysa. Many Sanskrit poems mention this place. Today Koh Mor (Mount Nysa of Greek legend) stands in Bajaur Agency. This mount is visible from Peshawar Valley.

It was here at the foot of mountain that Alexander reportedly camped and founded the Nysaean colony of the Greeks. The area was stronghold of Apraca or the Apracharajas, also known as Avacarajas, a local ruling dynasty of Gandhara. Some scholars like Cunningham have identified Nysa with Nagara Dionyopolis and locate it at Bagram (Afghanistan). Others believe it was Nissa in Parthia.

According to a legend, on his return from Nysa to join his fellow Olympians, Dionysus brought with him wine that had psychedelic effects. Arrian of Nicomedia (d 160 AD) was a Greek historian and senator of the Roman Empire. His book The Anabasis of the Alexander is the best source on the life, campaigns and achievements of Alexander. Arrian’s Anabasis comprises seven books. The fifth book has Chapter I with the title “Alexander at Nysa.” He writes: “In the country traversed by Alexander between the Kophen and the River Indus, they say that besides the cities already mentioned, there stood also the City of Nysa, which owned its foundation in Dionysus, and that Dionysos founded it when he conquered the Indians.”

He again writes: “When Alexander came to Nysa, the Nysaians sent out to him their president, whose name was Akouphis and along with him 30 deputies of their most eminent citizens, to entreat him to spare the city for the sake of the god. The deputies, it is said, on entering Alexander’s tent found him sitting in his armour, covered with dust from his journey, wearing his helmet and grasping his spear. They fell to the ground in amazement at the sight, and remained for a long time silent. But when Alexander had bidden them rise and to be of good courage, then Akouphis taking no speech thus addressed him.” (79)

Chapter II describes that Alexander permitted the Nysaians to retain their autonomy. Later on, Alexander requested Akouphis to send with him 300 of his best horsemen. He also took Akouphis’ son and his daughter’s son for his next expedition. Alexander visited Mount Meros or Mor with his companion cavalry and foot guards. There, Alexander saw ivy (sacred plant of the gods), laurel and other trees. He offered sacrifices to the god Dionysus. The Macedonians wove chaplets and crowned themselves with wreaths made of leaves. Alexander feasted with his friends and chanted hymns to the god of Meros, Dionysus. The Greeks also heard myths of Herakles beyond Nysa and the Rock of Aornos in Gandhara.

There are those who believe that the inhabitants of Nysa were not Indians, but descendants of companions of Alexander and parts of his army, who remained as invalids in India due to their wounds. Some of the isolated and indigenous people of Kabul, Meros, Pamir and Swat are important for such investigations.

Daedala: A military colony on the border

Quintus Curtius Rufus, was a Roman senator and historian. He compiled the History of Alexander the Great. Quintus died in 70 AD. Describing Daedala, a place close to Nysa, he writes, “From Nysa they came to a region called Daedala. The inhabitants had deserted their habitations and fled for safety to the trackless recesses of their mountain fortress. He therefore passed on to Acadira, which he found burned, and like Daedala deserted by the flight of the inhabitants.” (page 194)

According to William Woodthorpe Tarn’s book The Greeks in Bactria and India (2010), Daedala was a district in Bajaur (KP province). Probably the Daedalian Mountain was close to this location. He writes that, “Stephanus too had heard of Menander’s Daedala in India, which he calls an Indo Cretan city. Menander’s Daedala then was a military colony of mercenaries”. (Page 250) Ptolemy’s Daedala situated upon Lycia, Anatolia. Getzel M Cohen (2013) views that we do not know whether the settlers living at Daedala in India originated in Crete, Asia Minor or the Parapamisadai.

Acadira: story of a burned city

Quintus Curtius Rufus mentions this city with Daedala. Justin in Historiae speaks of mountains which he calls Daedali. General Cunningham calls it Mount Dantalok, which is three miles from Palodheri or Pelly, a place 40 miles distant from Pashkalavati (Hasht Nagar) in Peshawar Valley. Many geographers and historians like Ptolemy, Muller and Abbot have also tried to identify this place in north western India. The location is unidentified. This region was taken by storm during Alexander’s Cophen campaign. Muller calls it Candira and connects it with the Khond Mountain. Some historians call it Acadera.

Arigaion (Arigaeum): A mountain base of Indians

Arrian under Chapter XXIV, “Operations against the Aspasians,” writes:

“Alexander then crossed the mountains, and came to a city at their base, named Arigaion. He found that the inhabitants had burned the place and taken to flight. Here, Krateros, with his staff and the troops under his command, rejoined him, after having fully carried out all the orders given by the king. As the city seemed to occupy a very advantageous site, he commanded Krateros to fortify it strongly, and people it with as many natives of the neighbourhood as should consent to make it their home, together with any soldiers found unfit for further service. He then marched to a place where, as he had ascertained, most of the barbarians of that part of the country had taken refuge, and on reaching a certain mountain encamped at its base.” (pages 63 and 64)

After observing the advance of his enemies using fires, Alexander divided his forces into three parts: led by Alexander himself, Ptolemy son of Lagos and Leonnates. Later on, we read that Aspasians, Assakenians and Gouraians were defeated badly. From Justin’s Historiae we know that Alexander received the submission of Queen Cleophis. Ptolemy states that above 40,000 men were taken as prisoners. Thousands of oxen were captured. Alexander picked out the best oxen in beauty and size for agriculture in Macedonia. He then marched to invade the Assakenians who were ready with 20,000 cavalry and 30,000 infantry besides 30 elephants. He passed through the country of Gouraians that lived on the River Gouraios. The Indians, we are told, had no courage therefore they dispersed in several cities.

According to WJ Mcrindle (1896) the River Gouraios is the River Panjkora, which unites with the river of Swat, to form the Landai, a large affluent of the Kabul River. Panjkora means “five flowing waters.” The length of Panjkora River is 140 miles or 220km, at an elevation of 3,600 m (11,800 ft). It flows through Kumrat Valley, Upper and Lower Dir Districts in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The Panjkora River is the natural habitat of trout fish. The valley contains important sites of the Gandhara Grave Culture (1500-600 BC), Timergara, Balambat, Talash and others. Remains of prehistoric forts, altars and houses can be seen here.

Massaga: the capital of Queen Cleophis

Massaga, Massaka, Mazaga or Msoka was an ancient city of the Gandhara Satrapy.

The Indian border town of Massaga was the capital of the King Assakanos. He ruled the Assaceni; an Indian tribe that lived in the Valleys of Swat and Bunner.

Arrian writes that Assakanos, the king of that place, died in a battle before Alexander’s arrival. McCrindle in his book The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great (1896) writes, “Assakanos was succeeded by his mother (wife) whose name was Cleophis, and who according to Justin, bore a son whose paternity was ascribed to Alexander. In reference to this statement, Dr Bellew remarks that in the present day, several of the chiefs and ruling families in the neighbouring states of Chitral and Badakhshan boast a lineal descent from Alexander the Great.” (Page 335)

Alexander marched first to attack Massaga in the autumn of 327 BC, during his hill campaign in the Indus Valley. The Assakenoi faced Alexander with an army of 30,000 cavalry, 38,000 infantry and 30 elephants. They had fought bravely and offered stubborn resistance to the invader in many of their strongholds like cities of Ora, Bazira and Massaga. Assakenoi warriors were actually a serious threat to Alexander’s army, and they resisted bravely in many battles against the Macedonians.

Alexander himself sustained a serious wound to the ankle. When the king of Massaga was struck by a missile, the supreme command of the army passed to his mother, Cleophis. These people were also known as Ashvakas in Sanskrit, meaning "the Horse People." In a hand-to-hand encounter with the Greeks, 200 Indians were killed. Alexander employed the Phalanx formation and war engines that fired missiles against the Indians. The men who had previously captured Tyre were engaged in breaking the walls of the fortification. The people then left the city, arms in hand, and encamped on a small hill. Alexander captured the mother and daughter of Assakenos, the king of Massaga, while the rest of the people sought refuge in the city of Massaga in the Katgala Pass. The Macedonian army was confronted by Aphirices (a relative of Assakenos) in the Buner region. He was ultimately killed by his own men, and many natives took refuge on the Holy Rock, Aornus or Pir Sar.

Curtius, describing the romance between Alexander and the queen, writes: “Since the besieged townspeople now had no option but to surrender, a deputation came down to the king to seek a pardon, which was granted to them. Then the queen came with a group of ladies of noble birth, who made libations from golden bowls. The queen herself placed her little son at Alexander’s knees, and from him gained not only a pardon, but also the restitution of her former status, for she retained the title of queen. Some have held the belief that it was the queen’s beauty rather than Alexander’s compassionate nature that won her this, and it is a fact that she subsequently bore a son who was named Alexander, whoever his father was” (Curtius 8.10.33-36). Cleophis’s liaison with Alexander earned her the reputation of “the royal whore” (scortum regium). Curtius, Justin, and the Metz Epitome have all produced numerous stories about this queen. Gerard Hoet, a Dutch painter, engraved a painting entitled Queen Cleophis Offers Alexander the Great Wine in 1670.

Philostratus, a Greek sophist, observed: “Taxila, they tell us, is about as big as Nineveh and was fortified fairly well after the manner of Greek cities”

Diodoros writes in Bibliotheca Historica, the 17th book: “When the capitulation on those terms had been ratified by oaths, the Queen (of Massaga), to show her admiration of Alexander’s magnanimity, promised that she would fulfil all the stipulations. Then the mercenaries, in accordance with the terms of the agreement, immediately evacuated the city and, after retiring to a distance of 80 stadia, pitched their camp unmolested, without any thought of what was to happen” (Page 269). Alexander had sexual relations with Cleophis. Justin (perhaps following Cleitarchus) alleges in his Historiae: “Thence he marched to the Daedali mountains and the dominions of Queen Cleophis, who, after surrendering her kingdom, purchased its restoration by permitting the conqueror to share her bed, thus gaining by her fascinations what she had not gained by her valour. The offspring of this intercourse was a son, whom she called Alexander, the same who afterwards reigned as an Indian king. Queen Cleophis, because she had prostituted her chastity, was therefore called by the Indians the royal harlot” (Page 322).

Andrew Michael Chugg, in his book Alexander’s Lovers, writes: “Today in the Chitral region of Pakistan, in the vicinity of ancient Massaga, live the Kalash people, who continue vociferously to claim descent from Alexander’s army. The historian Michael Wood visited the clan for his TV series and book: In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great (1997, Page 7). Furthermore, it is reputed that the leaders of the Kalash assert that Alexander himself is their direct ancestor. The legend of the mountain queen and Alexander’s lost son seems to have achieved a kind of perpetuity. Babur (d.1530) described the ancient city of Massaga as Mashanagar in his Memoirs. Rennell identified this name with the Massaga of Alexander’s historians. Are 3,800 Kalash people descendants of Alexander the Great?”

According to Colonel John Biddulph (d 1921) in his book Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh, different rulers of states both north and south of the Hindu Kush claim that they descend from Alexander. Venetian traveller Marco Polo (13th Century) reported in his book that the royal dynasty of Badakhshan descended directly from Alexander” (Polo 2005: 37). In Gilgit, the Wakhan Princes are said to be entitled to this claim. In Wakhan, the Chitral rulers are named as the true descendants of Alexander the Great, and in Chitral, the distinction is assigned to the Darwaz rulers. Babur also mentions in his Memoirs that the Princes of Darwaz are descended from Alexander (Tribes of Hindoo Koosh, Page 146). Many of the Kalash people of Chitral, Hunza, Gilgit, and Nagar also claim their descent from Alexander. The Bushgalis of Chitral claimed them as their slaves. The Kalash people today speak the Kalasha and Khowar languages. They follow Hinduism, Animism, and Islam. Their main festivals are Chawmos, Chilm Joshi, and Uchal.

This ethnic group relates itself to the Indo-Aryan peoples. The Siah Posh people of the Hindukush are also of Greek descent or Slav origin. Prince Ghazanfar Ali Khan of Hunza and his wife Princess Rani Atiqa claim descent from Alexander the Great. A high delegation of the Hunza people travelled to Macedonia in July 2018. Prince Ghazanfar Ali Khan of Hunza was appointed Governor of Gilgit-Baltistan on 14 September 2018. Prince Ghazanfar Ali Khan has three sons: Prince Salim Khan, Prince Shehryar Khan, and Prince Salman Khan. In October 2019, Britain’s Duke and Duchess, Prince William and Princess Kate Middleton, visited Village Bumburet in the Chitral Region of the Hindukush Mountains, some 250 miles north of Islamabad, Pakistan. They mingled with the Kalasha community and showed interest in their dance, music and customs.

The capture of Bazira (Beira)

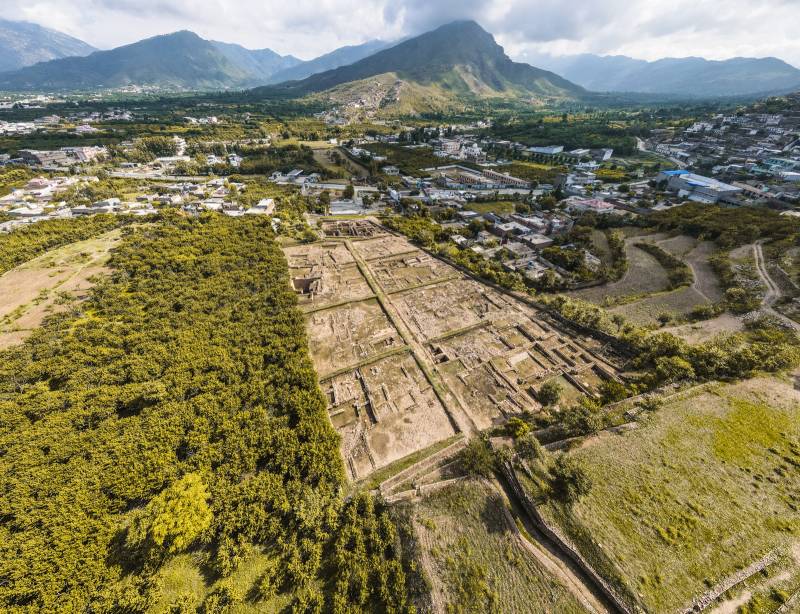

After the fall of the Massaga fortress, Alexander dispatched Koinos to Bazira. Arrian’s Anabasis informs us: “Alexander, on learning this, set out for Bazira, but as he knew that some of the barbarians of the neighbouring country were going to steal unobserved into the city of Ora, having been sent by Abisares for this very purpose, he directed his march first to that city” (Page 69). In the ensuing battle, 500 Indians were slain, and 70 were taken as prisoners. Barikot has been identified as Bazira or Beira. Sir Aurel Stein, a Hungarian and British archaeologist, was the first to visit this site in 1926. He identified this site with a village called Bir Kot (The Castle of Bir), now popularly known as Barikot.

Members of the Italian Archaeological Mission began excavations at Bazira in 1978, with four trenches dug between 1984 and 1990. Ancient relics, including pottery, weapons, vases, coins, and other artefacts, were discovered from the site. According to The International Association for Mediterranean and Oriental Studies (ISMEO), the archaeological site of Bazira/Barikot in Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, was inhabited from the 6th century BC to the 14th century AD. The site is located about 20 km from Mingora and Butkara Stupa in the Swat River Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

The city of Ora

Arrian writes in his book: “He then dispatched Koinos to Bazira, convinced that the inhabitants would capitulate on learning that Massaga had been captured. He moreover sent Attalos, Alketas, and Demetrios, the captain of cavalry, to another city, Ora, instructing them to draw a rampart around it and to invest it until his own arrival” (Page 69). The citizens of Ora, having lost hope, fled for refuge. They abandoned the town at midnight, retreating to the high mountains. This place is now identified as Udegram. Arrian’s further statement about Ora and its topography is as follows: “The siege of Ora did not cost Alexander much labour, for he captured the place at the first assault and got possession of all the elephants which had been left therein” (Page 70). In short, Alexander the Great established posts at Ora, Massaga, and Bazira to guard the region. He also established a junction on the Indus for his army.

Land of the Peukelaots

The Greek name for Pushkalavati was Peukelaotis. According to some accounts: “Alexander rejoined Hephaestion and Perdiccas at Peukelaotis. The local dynast Astis was defeated and killed, and his replacement was Sangaeus, who had the support of Taxiles, the ruler of the land beyond the Indus, who had determined to throw in his lot with Alexander.” This site has been identified with the Bala Hisar Mounds (today’s Charsada), 35 kilometres northeast of Peshawar. This is the region of the Swat and Kabul Rivers, which includes a site called Shaikhan. According to Sir Mortimer Wheeler, it was an Indo-Greek city with streets and grid plans. Many coins of Indo-Greek rulers from the 1st and 2nd centuries BC have been excavated from the site. This was the time when Pushkalavati was relocated from the original site at Bala Hisar to Shaikhan.

Fortified town of Orabatis

Arrian writes about Ora and Orabatis: “Alexander, on learning these particulars, was seized with an ardent desire to capture this mountain also, the story current about Herakles not being the least of the incentives. With this in view, he made Ora and Massaga strongholds for bridling the districts around them, and at the same time strengthened the defences at Bazira. The division under Hephaistion and Perdikkas fortified another city called Orabatis, in which they left a garrison and then marched on the River Indus. On reaching it, they began preparing a bridge to span the Indus in accordance with Alexander’s orders” (Page 78). According to WJ McCrindle, this site now stands with the name Arrabutt, a village on the left bank of the Landai River, where some old ruins once existed.

Identification of Aornos with Iskardo (Skardu)

Discussing the origin of Iskardo (Iskandro) or Skardu, John Biddulph (d.1921) in his book Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh writes: “In Gilgit, Hunza, Nager, and all the valleys to the westward, the name Iskardo is almost unknown, and the place was founded by Alexander, who named it Iskanderia, from which it was converted to its present form. It was probably this tradition that led Vigne to identify Iskardo with Aornos” (Page 145). Biddulph further states that from the earliest times, Iskardo was likely the seat of wealthier and more powerful princes than Gilgit, owing to its natural advantages. The Iskardo princes exerted social, political, and religious influence from Dardistan to the Hindoo Kush and Oxus Valley. The siege of Aornos was the last major operation carried out by Alexander before crossing the Indus River. Some scholars point out that there is no clear indication that they actually founded a settlement there.

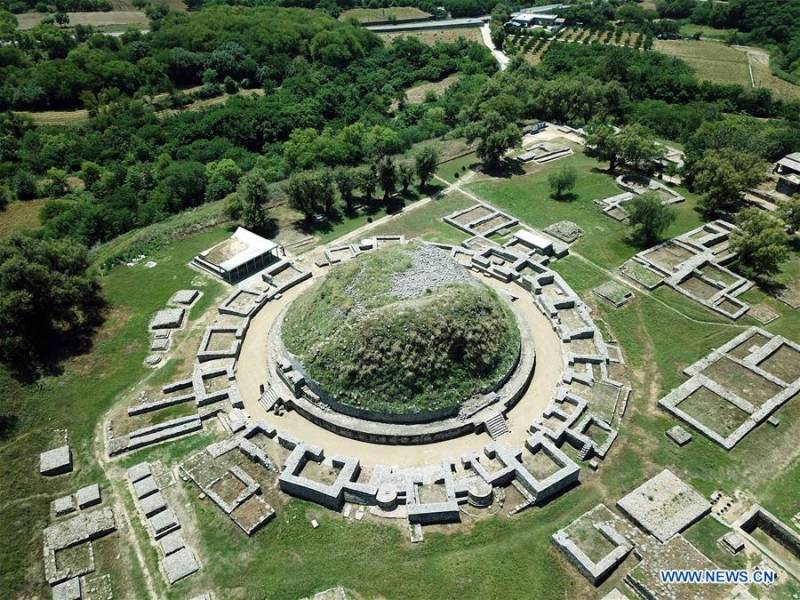

Taxila: A great and flourishing City

After the Aornos campaign, Alexander crossed the Indus River near Ohind, Attock, in the spring of 326 BC. Arrian writes: “When Alexander arrived at the River Indus, he found a bridge already made over it by Hephaistion, and two thirty-oared galleys, besides a great many small boats. He also found a present which had been sent by Taxiles the Indian, consisting of 200 talents of silver, 3000 oxen fattened for the shambles, 10,000 sheep or more, and 30 elephants. The same prince had also sent to his assistance a force of 700 horsemen, and these brought word that Taxiles surrendered into his hands his capital Taxila, the greatest of all the cities between the River Indus and the Hydaspes” (Page 83).

“When Alexander had crossed to the other side of the Indus, he again offered sacrifice according to his custom. Then, marching away from the Indus, he arrived at Taxila, a great and flourishing city, the greatest indeed of all the cities which lay between the River Indus and the Hydaspes. Taxiles, the governor of the city, and the Indians who belonged to it received him in a friendly manner, and he therefore added as much of the adjacent country to their territory as they requested. While he was there, Abisaris, the king of the Indians of the hill country, sent him an embassy which included his own brother and other grandees of his court. Envoys also came from Doxares, the chief of that province; these, like the others, brought presents. Here again, in Taxila, Alexander offered his customary sacrifices and celebrated a gymnastics and equestrian contest. Having appointed Philip, the son of Makhatas, as satrap of the Indians of that district, he left a garrison in Taxila and those soldiers who were invalided, and then moved on towards the River Hydaspes, for he had learned that Poros with the whole of his army lay on the other side of that river, resolved either to prevent him from making the passage or to attack him when crossing” (Page 92).

Alexander took with him 5,000 troops commanded by Taxiles and advanced towards the Hydaspes (Jhelum) to engage Porus in battle. Taxiles’s son, Omphis, had also made a formal submission along with his father. Their powerful neighbours, Abisares to the north and Porus to the east, received envoys from Alexander demanding submission. Abisares, being ill, excused himself, but Porus came out to fight.

The remains of Taxila city are located 35 kilometres west of Rawalpindi, Islamabad. It was originally built on the Bhir Mound. There was an Indo-Greek royal mint at Taxila, which issued coins for kings in the empire. Philostratus (d 247 AD), a Greek sophist, observed: “Taxila, they tell us, is about as big as Nineveh and was fortified fairly well after the manner of Greek cities” (Life of Apollonius 2.20). We can easily see Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman influences on Taxila. Bhir, Sirkap, and Jandial are important locations in Taxila. Sirkap was a local ruler whose summer residence was at Pirsar. Sir John Marshall excavated 12,000 coins belonging to Indo-Greek and Graeco-Bactrian kings of India. Sir Mortimer Wheeler also excavated Taxila. In 400 AD, Taxila was visited by Fa Hian, who calls it Chu sha shi lo, meaning “the several heads of Buddhism in India.” It was also called Takshasila (Chu cha shi lo) by later travellers, geographers, and writers.