Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for part III

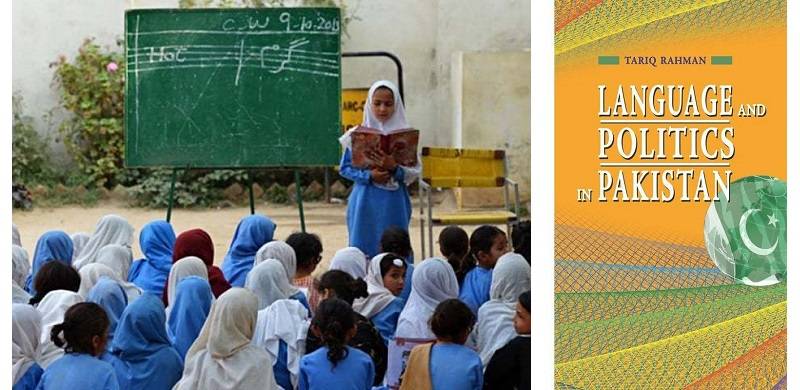

In 1994 I had to go to three new places: Quetta, Chitral and Bangladesh. In Quetta I had to research the Baloch and Brahvi language movements; in Chitral I had to investigate Khowar, the major language of Chitral, with a view to finding out whether there was a movement to promote it or not; and in Bangladesh there was the famous Bengali language movement (Bhasha Ondolan) which I had to research at first hand. In both the latter of these endeavours my former comrades-in-arms helped me again.

In Quetta I stayed with my younger brother, Ahmad, who was a surgeon with the rank of captain in the army. He received me at the airport as I descended from the plane on a June afternoon which was blistering in Islamabad but pleasant in Quetta. They had a small flat which was more than adequate for his wife Saba and little daughter, Mariam, who was now a toddler. In the next three weeks or so they extended such warm hospitality to me that I was touched. Munno would come to sing lullabies to me. Ahmad gave me his car which made it very convenient for me to travel all over the city in quest of interviewees, documents and books. In Islamabad somebody had given me a letter of introduction to a political leader, Jan Jamali. He later became the chief minister of Balochistan but was not so prominent at that time. He was very hospitable and helpful. He introduced me to people who provided me with much of the material I used. I also consulted the legislative assembly debates and saw children’s books in Balochi and Brahvi. In short, it was a very useful visit indeed. It was also my first visit to Quetta.

In Chitral my colleague and friend at PMA, Colonel Javed Mehr, Joji among friends, was the commandant of Chitral Scouts. I spoke to him and he invited me for a visit. The family wanted a holiday in Chitral and my mother also wanted to go because she had read about Kafiristan a long time ago. So, we all drove to Peshawar to Hana’s cousin Samina and her husband Junaid’s house. I had stayed in their house on several of my visits to Peshawar and enjoyed talking to their little son Bilal. This time, however, we only stayed for the night. The next day we caught a flight for Chitral. The plane was so small and flew with such obvious rattling and shaking that I was not sure whether it would ever cross the high mountains in the way. But it did and we landed at Chitral airport which was more than four thousand feet above sea level. The mountains all around were like the walls of a giant fort. Like Quetta’s mountains they were bare and rocky. But the valley itself was intensely green. In the background stood the towering peak of the snow-capped Tirich Mir. One could only marvel at the view.

The Scout’s Officers’ Mess was picturesque. It had a huge Chinar tree in its lawn beneath which we loved to sit breathing the cool, fresh mountains air. Joji came in the afternoon and welcomed me. He had not changed much. He was still bluff and genial and with an air of soldierly straight forwardness the best among the army officers possess. But he was married now, as was I, and had children. The relevance of mentioning marriage is that there was a time when some of us, including myself, Joji and Iftikhar, had thought of living on some sort of a farm with horses and dogs and not having obligations which marriage entails. Later everybody married with the exception of Colonel Iftikhar Hassan (ID) and this bucolic fantasy was forgotten. So, now that Joji was married, my wife and mother wanted to meet his wife. And sure enough they got their chance as she invited us for a dinner in their house which had fruit trees in the lawn. The ladies got along very well indeed. For his part, Joji provided me with a jeep in which I was driven by a highly skilled Scouts driver to Booni where an activist of the Khowar language movement, Inayatullah Faizi, lived. We reached there after a very rough drive of several hours but the place was picturesque and Faizi gave us several kinds of fruit for our meal. We also visited places like Garam Chashma only for sightseeing. Since I wanted to read the material in the archives of another officers’ mess of the Scouts, we drove there one day. Here the officer commanding had been one of my students at PMA. He gave us a very warm welcome and I interviewed some Khowar activists and read the material the British had preserved in the mess.

From there we took a jeep and travelled to the Bunburat valley in the Kalasha area which my mother still called Kafiristan. This was my mother’s dream and we were all fascinated with the scenery. However, the road was so narrow at places that we were frightened. At one place rocks started tumbling downhill and the driver stopped the jeep. I shouted to him to go on and he drove on. This was probably what saved us because if the rocks had become a mud slide, we could have been pushed down into the river thousands of feet below. I do not know, however, whether the rocks stopped falling or not and also whether the driver would have gone on or reversed the jeep if I had not peremptorily commanded him to go on. However, I thought, perhaps vainly, that I had saved the day. The valley was lovely and we posed with some of the Kalasha girls in their colourful headgear and necklaces of beads. We saw their wooden huts clinging precariously to the rocky mountains and their graveyard. But I found the creeping commercialism disturbing. People from the plains were giving them commercial values and also converting them. This meant that one of humanity’s oldest religion and languages – for converts abandoned their language too – were being lost for ever. It saddened me but the world moves on. We too moved back to Chitral.

Now that my research and the family’s sightseeing was over, we decided to go back and got our return flight booked. We said goodbye to Joji’s family and the mess staff and went to the airport. There we waited for the plane. We kept waiting and no plane appeared although there was not a cloud in the air. Then we were told that there was monsoon rain in the valleys below so the plane had turned back from the pass. The next day we heard that the plane could not even take off from Peshawar. This became a great embarrassment and a laughing matter between ourselves. My mother joked that Joji would repent of ever having invited us and we had better tell him we had come to stay for ever. Joji said this was normal and we need not worry. However, I was getting frustrated and one day I decided we would go down the pass by road. This was considered dangerous and it would take the whole day but this was what we decided to do. This time when we took off for the airport again in the morning it was after our final good bye to the grinning and much amused mess staff. I had made the final payment and cancelled lunch for the day. But this time too the plane did not arrive. Accordingly, we went to the wagon stop and booked seats for ourselves. Joji’s driver was incredulous as ladies hardly ever travelled by public transport. We were, however, resolved and Tania and Fahad were chortling with joy at the prospect of the legendary journey through the pass.

The wagon started climbing up the winding road to the top of the pass. The driver, who was a callow youth, adjusted the mirror so that he could see Hana. Then he started showing off: veering towards the ditch; driving fast; turning corners fast – this was his way of showing off to Hana. This amused my mother a lot though Hana herself was annoyed. I too was angry and also concerned at his antics. At last, being unable to control myself any longer at this ogling and risk-taking, I told him to slow down but this had only a temporary effect on him. It was only when we had descended in the plains that he calmed down. We reached Peshawar after sixteen hours journey and next day we drove back home.

The visit to Bangladesh was more problematic. I had hardly any savings left and I applied for none from the QAU, NIPS or the UGC being sure they would only sit on the application and never actually give me any money. Someone advised me to apply to the Hamdard Foundation of Hakeem Saeed (1920-1998) for a travel grant to Dhaka. I did apply but there was not much of a positive response. Then I met Hakeem Saeed personally in a seminar and he encouraged me to apply again. I told him that I would not like anyone to see my manuscript nor would I toe any given line. This is generally anathema to donors but Hakeem Saeed did not insist on doing any of these things. In fact, though I knew him only as a practitioner of traditional medicine, Saeed Sahib was a philanthropist and a patron of education who established a private university. His murder later made me very sad. So, probably because of his personal intervention, much to my surprise, I received a return ticket from Karachi to Dhaka. The stay would be financed by myself, of course.

I then wrote to Dhaka University requesting them for a room in the hostel or the faculty guest room. They agreed and I was now ready to go to Dhaka. But I was still a bit uneasy. I wanted a personal friend, or at least someone who knew me, to receive me at the airport. Hana also warned me that I would find it difficult to survive in Dhaka if I knew nobody at all. I then decided I would approach some former comrades from the army again. I told Hana – we were having a walk then – that I would ring up the military attaché in the Embassy of Bangladesh in Islamabad. She was most sceptical. After all, she reasoned, would not a senior officer of the Bangladesh army be inimical to a Pakistani former army officer? I said this was possible but there could also be some sort of comradeship though not an established old boys’ network. Next day I rang up the embassy and was connected to the military secretary, who was a brigadier. I gave him my name, the year I was in PMA and my company. He said he was there then and that he had held an appointment in a course senior to me. We set up an appointment and I went to see him in the embassy. I could not place him from our PMA days but he was very friendly and I got a visa immediately. What was even better was that he told me that his friend Brigadier Sharif Aziz would receive me at the airport. This made me feel better and I flew off to Karachi where I had a lecture at the American Cultural Center. Then, as always, to Chacha Mian’s house where Riaz and Shakeel took me, again as usual, to one of those roadside cafés which never close in Karachi – not even in those days of violence. I also met Anjum Siddiqui who was now in Karachi. He had dumped his first wife Duriya for an Iranian girl, Naghme, who had dumped him in turn when he told her that he wanted them to separate for some time. Now Anjum was desperately in love with a very attractive Pakistani girl whom he had met in New Zealand. He implored me to see this girl and persuade her to marry him. I told him that I would tell her whatever she asked me about his marriage accurately and truthfully. Anjum agreed and I did meet her but she said, among other things, that he was emotionally immature and unreliable. She also requested me to stop him from sending her flowers as she lived in a middle-class area and this would bring her nothing but disgrace. I agreed and told Anjum it was no good. Anjum was very disillusioned. However, he dropped me at the airport at dawn and I took off for Dhaka.

As soon as I was past immigration, I found the airport crowded. Everybody was talking at the same time and people seemed worried. Then I learned that there was a strike in the city and even the taxis could not move. I rang up Brigadier Sharif but the person who answered the phone did not understand me. So here was I, stuck at the airport. I was beginning to get worried when someone waved to me and said:

‘Dr Tariq Rahman I believe. My name is Brigadier Sharif’.

I could have cried for joy. It was so wonderful to see his welcoming smile. He told me that cars could move but he had got a bit late as we drove across the dead city.

‘Accommodation is expensive’, he told me

My heart sank as I quickly calculated to discover that I would finish up all my money before I could do my work if I stayed in such expensive places.

He took me to his home, a flat in a posh locality of Dhaka. I was so glad to be in a house like my own that I could hardly thank him adequately. His son brought me Archie comics to read and I spent the afternoon reading them. After tea he sent me in his car to the Dhaka University where I was supposed to stay. Here we found crowds of students chanting about something. They were so angry that I suddenly felt afraid. They did not know I had been against the military action in 1971but they knew I was from Pakistan – would I be safe? And then what kind of accommodation would it be?

In any case, nobody knew anything about my arrival and we had to come back. I was most embarrassed at having to spend the night in Brigadier Sharif’s house. The next day I went with him to his office. There I got the idea that I could sleep in the small room, meant as a dressing room, adjacent to the office. There was a small cot there and next to it was the bathroom. Brigadier Sharif said the place was not suitable for me but I insisted and he reluctantly agreed. He did insist, however, that I would have to have my meals in his house. I said I would take breakfast but for the rest of the day I would be away. So, with this arrangement I was much relieved. Now I had enough money to complete my research on the Bengali language movement.

Every morning I would take off for Dhaka city on a rickshaw pulled by a man or by a cyclist. It was most painful and embarrassing to see these emaciated men pulling rickshaws with well-dressed fat cats sitting in them. But there was no alternative so I too became an insensitive fat cat and was driven to places like the Bangla Academy and the Shaheed Minar and, of course, all the people I wanted to interview. Among them I was most struck by Dr. Murshid who took me for a dinner in one of Dhaka’s oldest restaurants. His wife was the gracious hostess and they told me much that I wanted to know. Another visit was to Dr. Kabir Chaudhry’s house in Dhanmondi. It was from this house that Munir Chaudhry, an activist of the language movement and a faculty member of the Dhaka University, had been taken away by mysterious armed men, said to be sent by the military, and never seen again. I was eating an excellent dinner when I was told this and I could hardly face the ladies – probably mother or aunt? or even sister? of Munir Chaudhry. All I could say was that I had come to find out the truth of the Bhasha Ondolan – what else could I say? The eldest lady, definitely the mother, had such vacant eyes that I mentioned them as a symbols of the pain of this unnecessary war in my book entitled Pakistan’s Wars (2022). Then news started coming that plague had broken out in India. I was not much alarmed when I heard it initially. Then came the really worrying news that it had come to Calcutta which, everybody said, was next door to Dhaka. Now I was worried that the flights to Dhaka would stop! But this did not stop me from working even when I was exhausted. But luckily the flights never stopped and I came back to Pakistan.

Click here for part III

In 1994 I had to go to three new places: Quetta, Chitral and Bangladesh. In Quetta I had to research the Baloch and Brahvi language movements; in Chitral I had to investigate Khowar, the major language of Chitral, with a view to finding out whether there was a movement to promote it or not; and in Bangladesh there was the famous Bengali language movement (Bhasha Ondolan) which I had to research at first hand. In both the latter of these endeavours my former comrades-in-arms helped me again.

In Quetta I stayed with my younger brother, Ahmad, who was a surgeon with the rank of captain in the army. He received me at the airport as I descended from the plane on a June afternoon which was blistering in Islamabad but pleasant in Quetta. They had a small flat which was more than adequate for his wife Saba and little daughter, Mariam, who was now a toddler. In the next three weeks or so they extended such warm hospitality to me that I was touched. Munno would come to sing lullabies to me. Ahmad gave me his car which made it very convenient for me to travel all over the city in quest of interviewees, documents and books. In Islamabad somebody had given me a letter of introduction to a political leader, Jan Jamali. He later became the chief minister of Balochistan but was not so prominent at that time. He was very hospitable and helpful. He introduced me to people who provided me with much of the material I used. I also consulted the legislative assembly debates and saw children’s books in Balochi and Brahvi. In short, it was a very useful visit indeed. It was also my first visit to Quetta.

In Chitral my colleague and friend at PMA, Colonel Javed Mehr, Joji among friends, was the commandant of Chitral Scouts. I spoke to him and he invited me for a visit. The family wanted a holiday in Chitral and my mother also wanted to go because she had read about Kafiristan a long time ago. So, we all drove to Peshawar to Hana’s cousin Samina and her husband Junaid’s house. I had stayed in their house on several of my visits to Peshawar and enjoyed talking to their little son Bilal. This time, however, we only stayed for the night. The next day we caught a flight for Chitral. The plane was so small and flew with such obvious rattling and shaking that I was not sure whether it would ever cross the high mountains in the way. But it did and we landed at Chitral airport which was more than four thousand feet above sea level. The mountains all around were like the walls of a giant fort. Like Quetta’s mountains they were bare and rocky. But the valley itself was intensely green. In the background stood the towering peak of the snow-capped Tirich Mir. One could only marvel at the view.

The Scout’s Officers’ Mess was picturesque. It had a huge Chinar tree in its lawn beneath which we loved to sit breathing the cool, fresh mountains air. Joji came in the afternoon and welcomed me. He had not changed much. He was still bluff and genial and with an air of soldierly straight forwardness the best among the army officers possess. But he was married now, as was I, and had children. The relevance of mentioning marriage is that there was a time when some of us, including myself, Joji and Iftikhar, had thought of living on some sort of a farm with horses and dogs and not having obligations which marriage entails. Later everybody married with the exception of Colonel Iftikhar Hassan (ID) and this bucolic fantasy was forgotten. So, now that Joji was married, my wife and mother wanted to meet his wife. And sure enough they got their chance as she invited us for a dinner in their house which had fruit trees in the lawn. The ladies got along very well indeed. For his part, Joji provided me with a jeep in which I was driven by a highly skilled Scouts driver to Booni where an activist of the Khowar language movement, Inayatullah Faizi, lived. We reached there after a very rough drive of several hours but the place was picturesque and Faizi gave us several kinds of fruit for our meal. We also visited places like Garam Chashma only for sightseeing. Since I wanted to read the material in the archives of another officers’ mess of the Scouts, we drove there one day. Here the officer commanding had been one of my students at PMA. He gave us a very warm welcome and I interviewed some Khowar activists and read the material the British had preserved in the mess.

From there we took a jeep and travelled to the Bunburat valley in the Kalasha area which my mother still called Kafiristan. This was my mother’s dream and we were all fascinated with the scenery. However, the road was so narrow at places that we were frightened. At one place rocks started tumbling downhill and the driver stopped the jeep. I shouted to him to go on and he drove on. This was probably what saved us because if the rocks had become a mud slide, we could have been pushed down into the river thousands of feet below. I do not know, however, whether the rocks stopped falling or not and also whether the driver would have gone on or reversed the jeep if I had not peremptorily commanded him to go on. However, I thought, perhaps vainly, that I had saved the day. The valley was lovely and we posed with some of the Kalasha girls in their colourful headgear and necklaces of beads. We saw their wooden huts clinging precariously to the rocky mountains and their graveyard. But I found the creeping commercialism disturbing. People from the plains were giving them commercial values and also converting them. This meant that one of humanity’s oldest religion and languages – for converts abandoned their language too – were being lost for ever. It saddened me but the world moves on. We too moved back to Chitral.

It was most painful and embarrassing to see these emaciated men pulling rickshaws with well-dressed fat cats sitting in them. But there was no alternative so I too became an insensitive fat cat and was driven to places like the Bangla Academy and the Shaheed Minar and, of course, all the people I wanted to interview

Now that my research and the family’s sightseeing was over, we decided to go back and got our return flight booked. We said goodbye to Joji’s family and the mess staff and went to the airport. There we waited for the plane. We kept waiting and no plane appeared although there was not a cloud in the air. Then we were told that there was monsoon rain in the valleys below so the plane had turned back from the pass. The next day we heard that the plane could not even take off from Peshawar. This became a great embarrassment and a laughing matter between ourselves. My mother joked that Joji would repent of ever having invited us and we had better tell him we had come to stay for ever. Joji said this was normal and we need not worry. However, I was getting frustrated and one day I decided we would go down the pass by road. This was considered dangerous and it would take the whole day but this was what we decided to do. This time when we took off for the airport again in the morning it was after our final good bye to the grinning and much amused mess staff. I had made the final payment and cancelled lunch for the day. But this time too the plane did not arrive. Accordingly, we went to the wagon stop and booked seats for ourselves. Joji’s driver was incredulous as ladies hardly ever travelled by public transport. We were, however, resolved and Tania and Fahad were chortling with joy at the prospect of the legendary journey through the pass.

The wagon started climbing up the winding road to the top of the pass. The driver, who was a callow youth, adjusted the mirror so that he could see Hana. Then he started showing off: veering towards the ditch; driving fast; turning corners fast – this was his way of showing off to Hana. This amused my mother a lot though Hana herself was annoyed. I too was angry and also concerned at his antics. At last, being unable to control myself any longer at this ogling and risk-taking, I told him to slow down but this had only a temporary effect on him. It was only when we had descended in the plains that he calmed down. We reached Peshawar after sixteen hours journey and next day we drove back home.

The visit to Bangladesh was more problematic. I had hardly any savings left and I applied for none from the QAU, NIPS or the UGC being sure they would only sit on the application and never actually give me any money. Someone advised me to apply to the Hamdard Foundation of Hakeem Saeed (1920-1998) for a travel grant to Dhaka. I did apply but there was not much of a positive response. Then I met Hakeem Saeed personally in a seminar and he encouraged me to apply again. I told him that I would not like anyone to see my manuscript nor would I toe any given line. This is generally anathema to donors but Hakeem Saeed did not insist on doing any of these things. In fact, though I knew him only as a practitioner of traditional medicine, Saeed Sahib was a philanthropist and a patron of education who established a private university. His murder later made me very sad. So, probably because of his personal intervention, much to my surprise, I received a return ticket from Karachi to Dhaka. The stay would be financed by myself, of course.

I then wrote to Dhaka University requesting them for a room in the hostel or the faculty guest room. They agreed and I was now ready to go to Dhaka. But I was still a bit uneasy. I wanted a personal friend, or at least someone who knew me, to receive me at the airport. Hana also warned me that I would find it difficult to survive in Dhaka if I knew nobody at all. I then decided I would approach some former comrades from the army again. I told Hana – we were having a walk then – that I would ring up the military attaché in the Embassy of Bangladesh in Islamabad. She was most sceptical. After all, she reasoned, would not a senior officer of the Bangladesh army be inimical to a Pakistani former army officer? I said this was possible but there could also be some sort of comradeship though not an established old boys’ network. Next day I rang up the embassy and was connected to the military secretary, who was a brigadier. I gave him my name, the year I was in PMA and my company. He said he was there then and that he had held an appointment in a course senior to me. We set up an appointment and I went to see him in the embassy. I could not place him from our PMA days but he was very friendly and I got a visa immediately. What was even better was that he told me that his friend Brigadier Sharif Aziz would receive me at the airport. This made me feel better and I flew off to Karachi where I had a lecture at the American Cultural Center. Then, as always, to Chacha Mian’s house where Riaz and Shakeel took me, again as usual, to one of those roadside cafés which never close in Karachi – not even in those days of violence. I also met Anjum Siddiqui who was now in Karachi. He had dumped his first wife Duriya for an Iranian girl, Naghme, who had dumped him in turn when he told her that he wanted them to separate for some time. Now Anjum was desperately in love with a very attractive Pakistani girl whom he had met in New Zealand. He implored me to see this girl and persuade her to marry him. I told him that I would tell her whatever she asked me about his marriage accurately and truthfully. Anjum agreed and I did meet her but she said, among other things, that he was emotionally immature and unreliable. She also requested me to stop him from sending her flowers as she lived in a middle-class area and this would bring her nothing but disgrace. I agreed and told Anjum it was no good. Anjum was very disillusioned. However, he dropped me at the airport at dawn and I took off for Dhaka.

As soon as I was past immigration, I found the airport crowded. Everybody was talking at the same time and people seemed worried. Then I learned that there was a strike in the city and even the taxis could not move. I rang up Brigadier Sharif but the person who answered the phone did not understand me. So here was I, stuck at the airport. I was beginning to get worried when someone waved to me and said:

‘Dr Tariq Rahman I believe. My name is Brigadier Sharif’.

I could have cried for joy. It was so wonderful to see his welcoming smile. He told me that cars could move but he had got a bit late as we drove across the dead city.

‘Accommodation is expensive’, he told me

My heart sank as I quickly calculated to discover that I would finish up all my money before I could do my work if I stayed in such expensive places.

He took me to his home, a flat in a posh locality of Dhaka. I was so glad to be in a house like my own that I could hardly thank him adequately. His son brought me Archie comics to read and I spent the afternoon reading them. After tea he sent me in his car to the Dhaka University where I was supposed to stay. Here we found crowds of students chanting about something. They were so angry that I suddenly felt afraid. They did not know I had been against the military action in 1971but they knew I was from Pakistan – would I be safe? And then what kind of accommodation would it be?

In any case, nobody knew anything about my arrival and we had to come back. I was most embarrassed at having to spend the night in Brigadier Sharif’s house. The next day I went with him to his office. There I got the idea that I could sleep in the small room, meant as a dressing room, adjacent to the office. There was a small cot there and next to it was the bathroom. Brigadier Sharif said the place was not suitable for me but I insisted and he reluctantly agreed. He did insist, however, that I would have to have my meals in his house. I said I would take breakfast but for the rest of the day I would be away. So, with this arrangement I was much relieved. Now I had enough money to complete my research on the Bengali language movement.

Every morning I would take off for Dhaka city on a rickshaw pulled by a man or by a cyclist. It was most painful and embarrassing to see these emaciated men pulling rickshaws with well-dressed fat cats sitting in them. But there was no alternative so I too became an insensitive fat cat and was driven to places like the Bangla Academy and the Shaheed Minar and, of course, all the people I wanted to interview. Among them I was most struck by Dr. Murshid who took me for a dinner in one of Dhaka’s oldest restaurants. His wife was the gracious hostess and they told me much that I wanted to know. Another visit was to Dr. Kabir Chaudhry’s house in Dhanmondi. It was from this house that Munir Chaudhry, an activist of the language movement and a faculty member of the Dhaka University, had been taken away by mysterious armed men, said to be sent by the military, and never seen again. I was eating an excellent dinner when I was told this and I could hardly face the ladies – probably mother or aunt? or even sister? of Munir Chaudhry. All I could say was that I had come to find out the truth of the Bhasha Ondolan – what else could I say? The eldest lady, definitely the mother, had such vacant eyes that I mentioned them as a symbols of the pain of this unnecessary war in my book entitled Pakistan’s Wars (2022). Then news started coming that plague had broken out in India. I was not much alarmed when I heard it initially. Then came the really worrying news that it had come to Calcutta which, everybody said, was next door to Dhaka. Now I was worried that the flights to Dhaka would stop! But this did not stop me from working even when I was exhausted. But luckily the flights never stopped and I came back to Pakistan.