Two years ago, in May 2018, the 25th Constitutional Amendment Bill sailed through the National Assembly, the Senate, the provincial assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and finally accent by the president. Between the National Security Committee meeting to decide the merger on May 18 to the president finally signing into law on May 31, the entire exercise was completed in less than two weeks. The exercise included the unprecedented convening of the Pakhtunkhwa provincial assembly session on a Sunday to pass it with two thirds majority on the last day of its five-year term.

All seven tribal agencies were thus merged into the province, the FCR abolished, the jurisdiction of superior courts extended, the president and the governor divested of powers to make laws for the region and the provincial laws extended to the tribal areas. Henceforth, the provincial assembly, instead of the president, were to make laws for the region. The special regulations issued by the president and governor from time to time were to be replaced with laws by the provincial assembly. A year later, in July 2019, elections to 16 provincial assembly seats from the newly merged tribal districts were also held, completing the process of merger.

But the picture two years after the merger is darker than before.

The presidential regulation which permitted setting up of ‘internment centres’ in tribal areas to keep terrorists until their trials was extended to the whole province. Instead of extending provincial laws to it, the draconian ‘Action in Aid of Civil Power Regulation’ for tribal areas was extended to the non-tribal districts as well. The horror chambers and the Guantanamo bay prisons that were confined only to tribal areas in the name of internment centres were thus allowed to be set up anywhere in the province.

A regulation called ‘Interim System of Administration of Justice in FATA 2018’ had also been issued for the administration of merged tribal districts till formalities of merger were completed, and representatives of tribal districts were elected to the provincial assembly. People were assured that the provincial assembly when completed with the election of members from tribal districts would change it.

However, despite the election of 16 members from tribal districts, it has not been done. Why? Clause 52-2 in the Regulation states, “The provisions of this Regulation shall remain in force until complete merger of FATA with the province. Taking the plea that merger is not yet complete, the Regulation has neither been changed nor replaced.

Little is known about the number of internment centres, where set up, how many held in each and for what crimes, how many have died in custody in these horror chambers and whether court trials have begun.

Hundreds of security check posts continue to straddle across tribal areas, particularly in North and South Waziristan and people facing humiliation at these posts. Instead of being manned by police, these are manned by the military, bringing face to face the army with the people in unsavoury confrontations. Why this insistence on the military manning check posts? If militants have been driven out, as is claimed and the areas merged in the province, why is policing still being done by the army and not by the police?

With peace claimed to have returned, why is it that tribal districts are still treated as no-go areas? Even a delegation of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) that wanted to visit victims of Kharqamar incident for condolences was turned back. If there is nothing to hide, why stop people from visiting these areas?

Tribal people displaced from their homes during military operations like Zarb-e-Azb continue to live in temporary camps and are not being allowed to go back. Why? The HRCP delegation was also not permitted to meet the inmates of Dattakhel camp meant for the displaced tribal people.

The tribal districts were promised more funds for development at the time of merger. However, instead the government last month diverted over Rs20 billion earmarked in the current year for the development schemes meant for displaced persons to “security enhancement.” The people of North and South Waziristan have been protesting against their non-rehabilitation but their protests have fallen on deaf ears.

Worse still is the record of impunity of crimes against the people. No judicial probe has been held in the Kharqamar incident that took place on May 26, 2019 in which over a dozen activists of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) were killed. No one has heard about probe in the kidnapping and dumping of the dead body of SP Tahir Dawar in Afghanistan a few meters away from the border.

The recorded video interview of a young boy Hayatullah complaining of harassment of the women of his family at the hands of security personnel remains un-investigated. More recently there has been deafening silence over the killing of PTM activist Arif Wazir, the 18th member of the family killed at the hands of militants. There is no explanation of the mysterious resurgence of militants in the tribal areas, particularly in North and South Waziristan.

Security mines laid in the past have not been removed resulting in the loss of lives and maiming of innocent people every now and then. In the case of any untoward incident, the entire areas are cordoned and people humiliated and tortured in the name of search operations, the latest such incident occurring just last Monday near Mirali in North Waziristan.

The real integration will not even begin to take place until militants are stopped from resurrecting; until the recurring crimes taking place against its people with impunity are probed and punished; until the area is demilitarised and decolonised in the real sense. What is happening in tribal districts is not the result of some intra-tribal dispute. It is a result of state policies. It will not be addressed by tribal jirgas. This calls for a truth commission. If there is any one lesson to be learnt from the last two years of merger it is this.

The writer is a former senator

All seven tribal agencies were thus merged into the province, the FCR abolished, the jurisdiction of superior courts extended, the president and the governor divested of powers to make laws for the region and the provincial laws extended to the tribal areas. Henceforth, the provincial assembly, instead of the president, were to make laws for the region. The special regulations issued by the president and governor from time to time were to be replaced with laws by the provincial assembly. A year later, in July 2019, elections to 16 provincial assembly seats from the newly merged tribal districts were also held, completing the process of merger.

But the picture two years after the merger is darker than before.

The presidential regulation which permitted setting up of ‘internment centres’ in tribal areas to keep terrorists until their trials was extended to the whole province. Instead of extending provincial laws to it, the draconian ‘Action in Aid of Civil Power Regulation’ for tribal areas was extended to the non-tribal districts as well. The horror chambers and the Guantanamo bay prisons that were confined only to tribal areas in the name of internment centres were thus allowed to be set up anywhere in the province.

A regulation called ‘Interim System of Administration of Justice in FATA 2018’ had also been issued for the administration of merged tribal districts till formalities of merger were completed, and representatives of tribal districts were elected to the provincial assembly. People were assured that the provincial assembly when completed with the election of members from tribal districts would change it.

However, despite the election of 16 members from tribal districts, it has not been done. Why? Clause 52-2 in the Regulation states, “The provisions of this Regulation shall remain in force until complete merger of FATA with the province. Taking the plea that merger is not yet complete, the Regulation has neither been changed nor replaced.

Little is known about the number of internment centres, where set up, how many held in each and for what crimes, how many have died in custody in these horror chambers and whether court trials have begun.

Hundreds of security check posts continue to straddle across tribal areas, particularly in North and South Waziristan and people facing humiliation at these posts. Instead of being manned by police, these are manned by the military, bringing face to face the army with the people in unsavoury confrontations. Why this insistence on the military manning check posts? If militants have been driven out, as is claimed and the areas merged in the province, why is policing still being done by the army and not by the police?

With peace claimed to have returned, why is it that tribal districts are still treated as no-go areas? Even a delegation of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) that wanted to visit victims of Kharqamar incident for condolences was turned back. If there is nothing to hide, why stop people from visiting these areas?

Tribal people displaced from their homes during military operations like Zarb-e-Azb continue to live in temporary camps and are not being allowed to go back. Why? The HRCP delegation was also not permitted to meet the inmates of Dattakhel camp meant for the displaced tribal people.

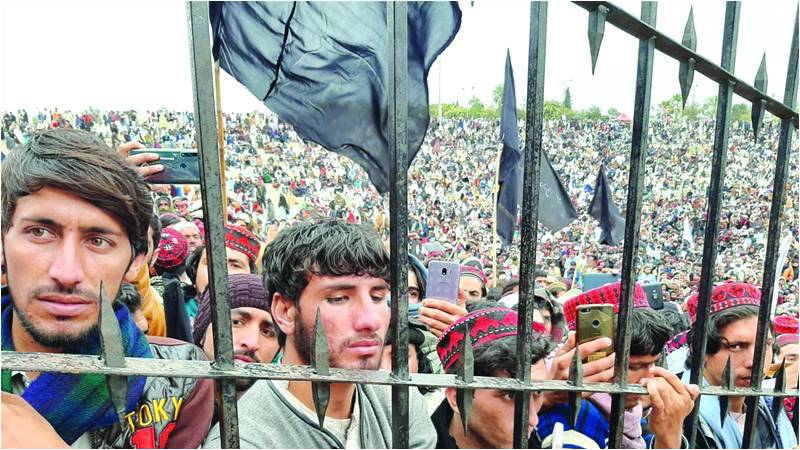

The tribal districts were promised more funds for development at the time of merger. However, instead the government last month diverted over Rs20 billion earmarked in the current year for the development schemes meant for displaced persons to “security enhancement.” The people of North and South Waziristan have been protesting against their non-rehabilitation but their protests have fallen on deaf ears.

Worse still is the record of impunity of crimes against the people. No judicial probe has been held in the Kharqamar incident that took place on May 26, 2019 in which over a dozen activists of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) were killed. No one has heard about probe in the kidnapping and dumping of the dead body of SP Tahir Dawar in Afghanistan a few meters away from the border.

The recorded video interview of a young boy Hayatullah complaining of harassment of the women of his family at the hands of security personnel remains un-investigated. More recently there has been deafening silence over the killing of PTM activist Arif Wazir, the 18th member of the family killed at the hands of militants. There is no explanation of the mysterious resurgence of militants in the tribal areas, particularly in North and South Waziristan.

Security mines laid in the past have not been removed resulting in the loss of lives and maiming of innocent people every now and then. In the case of any untoward incident, the entire areas are cordoned and people humiliated and tortured in the name of search operations, the latest such incident occurring just last Monday near Mirali in North Waziristan.

The real integration will not even begin to take place until militants are stopped from resurrecting; until the recurring crimes taking place against its people with impunity are probed and punished; until the area is demilitarised and decolonised in the real sense. What is happening in tribal districts is not the result of some intra-tribal dispute. It is a result of state policies. It will not be addressed by tribal jirgas. This calls for a truth commission. If there is any one lesson to be learnt from the last two years of merger it is this.

The writer is a former senator