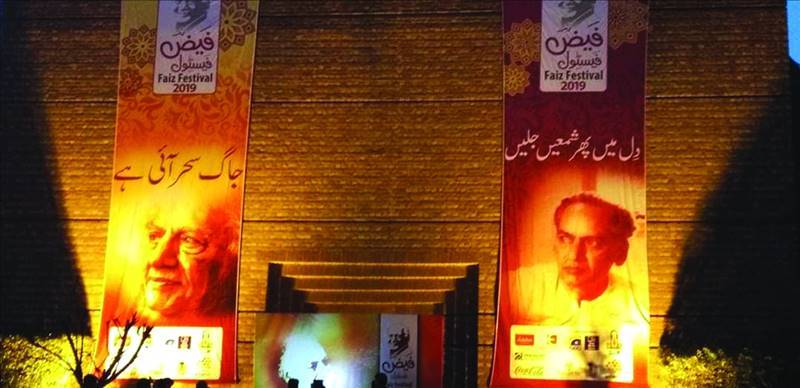

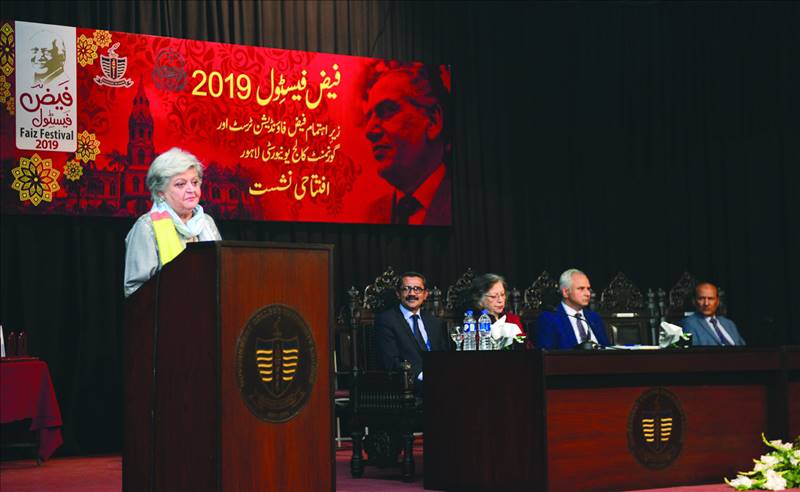

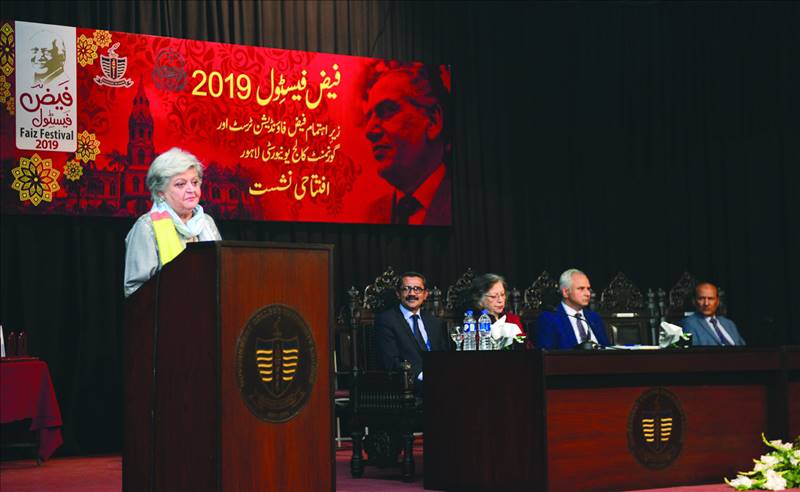

The Faiz International Festival (FIF) has actually become the harbinger of the onset of the chill which marks the transition from summer to winter. This year it also came as a welcome relief from the political theatre in the country surrounding the declining health of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif and the fallout from the eventually-aborted dharna of Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman in Islamabad. Nevertheless, even a cursory look at the Faiz Festival programme this year revealed a lot more of the same and some surprising new content. One was very surprised to have Kaifi Azmi once again as the “keynote” focus of the current year – last year Kaifi Azmi’s birth centenary was celebrated at exactly the same venue by the FIF in the presence of Azmi’s daughter, the actress Shabana Azmi and son-in-law, the poet Javed Akhtar. One felt that perhaps renewed attention on the poet this year was not really needed, especially given the fact that there were four other literary personalities vying for attention with birth centenaries this year just like Kaifi, namely the Progressives Zaheer Kashmiri, Majrooh Sultanpuri and Qateel Shifai; and non-progressive but equally important literary critic Muhammad Hasan Askari. In fact, given that both Majrooh and Qateel became immensely famous in the film world as lyricists and songwriters, a panel could have especially been created for remembering both of them in place of repetitive panels like the two panels titled “Pakistan: The Way Forward” involving politicians from virtually the same political parties, and the panel on “Gulshan-e-Yaad” remembering the three prominent female writers Altaf Fatima, Khalida Hussain and Fahmida Riaz, who all passed away last year (since virtually the same panel was created for this year’s Lahore Literature Festival back in February). In fact, this year marked the 50th death anniversary of the untimely death of Makhdoom Mohiuddin, a towering communist poet from the Deccan who indeed deserves to be better known and in fact acknowledged by many as a superior poet – perhaps even more so than the often programmatic poetry of Kaifi. Perhaps a lack of research or imagination by the FIF team, or both?

However one towering Punjabi writer and poet who was fortunate enough to be remembered on Day 1 of the FIF on her birth was Amrita Pritam. This was done by means of a tastefully-done dramatic rendition titled Men Tenun Fer Milaan Gi of the life and loves of Pritam by Sarmad Khoosat (as the poet Sahir Ludhianvi and then as Pritam’s artist-husband Imroz). Khoosat switched effortlessly between Pritam’s lover Sahir and her husband Imroz, now rendering Amrita’s heart-rending elegy to the ravaged daughters of the Punjab in the wake of the 1947 Partition Aj Aakhan Waris Shah Nun and Sahir’s equally moving poem on the hollow grandeur of the Taj Mahal; and then as the easel-loving Imroz. In fact, Nimra Bucha effortlessly held her own as the Punjabi doyenne with her luminous monologues and renderings of Pritam’s Punjabi poetry. It was noteworthy that the diction of the play was in Punjabi, given the Punjabi milieu and language of the three characters in the play. A minor quibble being that the play did not shed light on why Pritam walked out of an arranged marriage to her first husband; and secondly the play revolved too much around Pritam’s male protagonists Sahir and Imroz and insufficiently focused on the battles she fought against family and society to become the heroine of myth and legend that she became.

It was a dispiriting experience to walk in on a panel commemorating the three aforementioned Pakistani women writers right after such an uplifting drama on Pritam’s struggles and triumphs. Despite the fact that the panel commemorating three of our most distinguished writers - Altaf Fatima, Khalida Husain and Fahmida Riaz who all passed away last year – consisted of a senior critic Asif Farrukhi and distinguished panelists like Masood Ashar, Asghar Nadeem Syed and Dr Arfa Syeda Zehra, the discussion noted that though death brought the three writers closer to each other, each of them had an experience, training, style and ideology different to each other. The absence of two other important female writers, one each from Pakistan and India, Begum Perveen Atif (who also passed away last year) and Begum Masroor Jahan (who passed away earlier this year) on this panel was galling; perhaps their addition could have added something different and fresh to the panel, and saved it from a mere regurgitation of similar observations elsewhere. Also, Enver Sajjad, another towering Progressive writer who also passed away last year and ironically had a major role in creating the venue where the FIF was held, was particularly felt. Perhaps a better way to repeat this panel would have been to pay a dramatic tribute to the three departed writers as was the case with Amrita Pritam or to have a dramatic reading of one of the short-stories or extracts from these writers to give the audience a better idea of their work and worth.

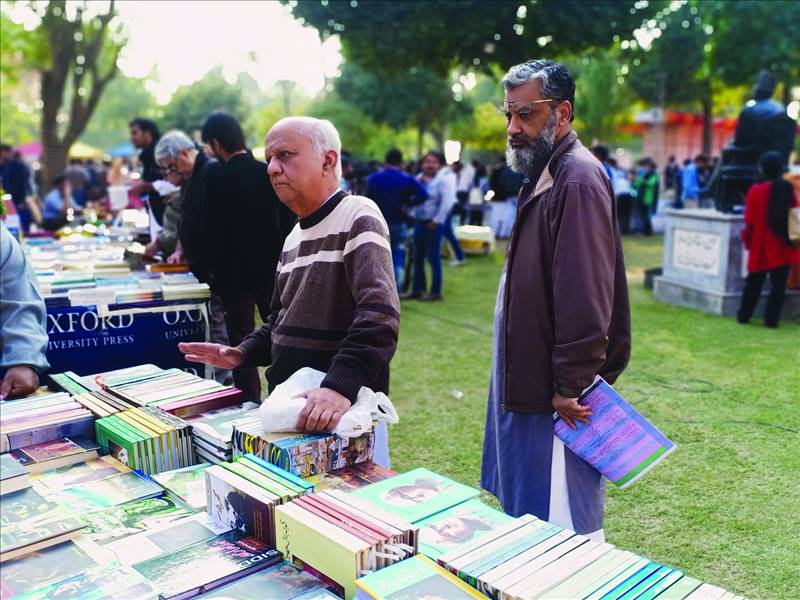

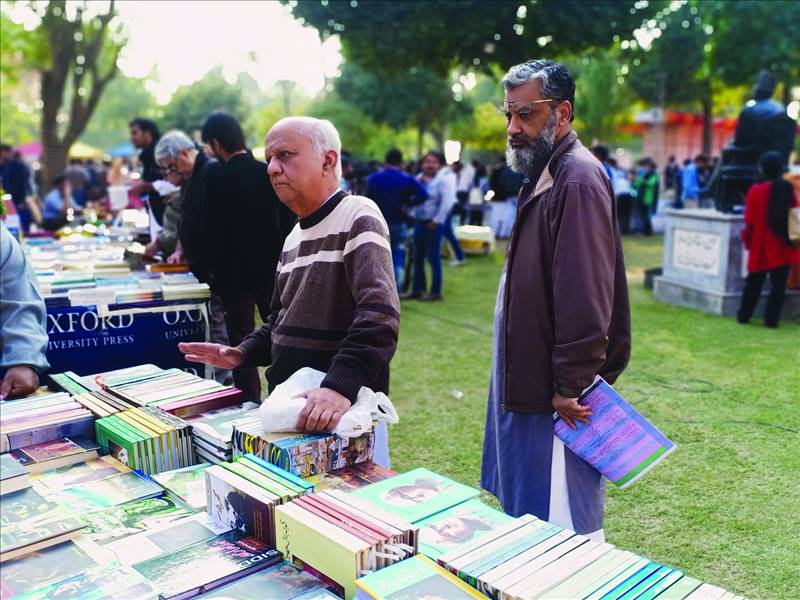

Perhaps one of the best sessions on Day 1 of the FIF was the book launch of Prison Interlude by Zafarullah Poshni, the last living survivor of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case against the Liaquat Ali Khan government in 1951. It was heartening to note the presence of many young people in the session, thereby proving that there is yet life in this cautionary tale from a seemingly bygone era. The most riveting conversation was by noted columnist Babar Sattar who said that the book talks about an event which continues to be on repeat in Naya Pakistan, as governments were still creating military courts and not only did this come under the Official Secrets Act, but ordinary people were not allowed to attend proceedings; and the issue of the “class” of jail was still relevant in the case of the under-trial former prime ministers Nawaz Sharif and Shahid Khaqan Abbasi. He wryly added that the young people not aware of the incident in the age of mass media and marginalization in textbooks should not think that they had missed anything. The book launch marked a welcome emphasis on translations at the FIF, since translated works or a discussion on translation had been notoriously absent in preceding years. A minor miracle being that the author himself managed to translate his book into English at the age of 94, underscoring the value of translating other seminal Urdu reminiscences into English like Rauf Malik’s enlightening autobiography Surkh Siyasat and Major Ishaq’s book on the trial and murder of young communist Hasan Nasir in 1960 (the latter being one of the prominent accused in the 1951 Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case).

Another huge pleasant surprise was the panel on “Lahore: City of Literature”, organized after UNESCO’s recent announcement of that Pakistani city as one of its worldwide Cities of Literature. The panel featured the senior writer and poet Amjad Islam Amjad along with the Commissioner of Lahore and Amina Ali, who had done the homework leading to the aforementioned distinction for Lahore. Amjad charmingly kept the whole panel together by sharing amusing and instructive anecdotes about some of Lahore’s distinguished poets and writers like Ehsan Danish, Sahir Ludhianvi and Chiragh Hasan Hasrat. He lamented the loss of the tradition among Lahore’s writers of giving space to various ideological views, as well as the additional challenged of the expansion of Lahore and the recurrent smog.

Day 2 at the FIF began with a panel on the influence of Faiz on contemporary poetry, meaning the poetry of what are usually deemed “regional” languages. Dr Ishaq Samejo said that the great Sindhi poet Shaikh Ayaz learned from Faiz and some of his best political poetry was written in jail, like the latter; Sadia Kamal arrived late for her panel and spent more time in talking about Seraiki resistance poetry in general than the topic of the panel; Fatima Hasan noted how close Sheikh Ayaz and Fahmida Riaz were to Faiz in their style, she herself started writing under the influence of Faiz; Allah Baksh Bozdar talked about how three generations of Balochis called Faiz a wali, and how Faiz and Jalib were among a handful of Punjabis who the Baloch loved; Ahmad Salim, the noted Punjabi poet talked about he himself had learnt about Heer Waris Sah and Amrita Pritam from Faiz and also lamented that had Faiz written a few more Punjabi poems in addition to the 6-7 poems he had written, his place in Punjabi letters would have been assured; noted human rights activist and left-wing Pakhtun politician Afrasiab Khattak talked about how Faiz was a champion of diversity and did not want to see the Urdu language ensconced in Pakistan by force.

Mohammed Hanif has of late been a fixture at literary festivals both in Pakistan and abroad, and a regular at the FIF. This time he talked with lawyer and novelist Osama Siddique about the recent Urdu translation of his novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes by KJashif Raza. His hilarious description of the whole process of how the novel eventually came to be translated after seven long years, and his travails after being rejected by a major publisher from Lahore were instructive. He also talked about his own fresh take on resistance poetry, “from resistance, you can’t have a lousy poem”, case in point being Barrister Aitzaz Ahsan’s poem Kal, Aaj aur Kal, which became an anthem for the anti-Musharraf Lawyers’ Movement. He was surprisingly less forthcoming when asked to offer by way of advice about writers who had inspired him and what young people should read today, perhaps betraying his lack of knowledge about what is being published even in Urdu (apart from what his friends’ write) and other Pakistani languages. The conversation with Hanif was similar in scope as was his conversation with Harris Khalique last year at FIF; perhaps since Hanif has been a journalist for much longer before than he became a novelist, he should have been utilized for the panels on media and journalism like the ones on “Using Media to Address Social Issues”, “Aaj ke Daur Men Inqalabi Sahafat” and “Digital Media in Pakistan” at this year’s FIF. When the same writers are invited repeatedly every year, even their humour gets stale! On the contrary, there have been several capable, emerging writers who have written debut or new novels in English, like Haroon Khalid and Uzma Aslam Khan who could have provided the audience with some refreshing insights about English fiction writing in Pakistan.

Zehra Nigah missed out on the last FIF due to ill health and her panel was duly conducted by Dr Arfa Zehra. However this year in a panel again featuring the latter and moderated by Qasim Jafri, Nigah talked about the genres of poetry. The moderator and in turn the panelists wisely decided to leave the remaining 31 genres of poetry alone and talk about only 3-4 aspects namely ghazal, nazm, marsiya and qasida. When prompted by Jafri as to the greatest poets among the 1,000 poets who were published, the panelists agreed on Mir, Ghalib and Iqbal. The often-times boring, academic discussion was regaled by recitations from the marsiyas of Josh and Mir Anees.

2019 also marks the centennial of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in Amritsar in April 1919 and as such there was a panel on it at the FIF. It was interesting to note the presence of Punjabi poet and industrial management academic Arvinder Chamak from Amritsar, whose grandfather was survivor of the massacre. The panel began by noting that the massacre represented the fact that violence was central to colonialism; that Punjabi anti-British agitation in the wake of the massacre gave the lie to claims of the Punjabis always being collaborators with outsiders. Chamak very movingly spoke about the gory details of the Massacre as handed down to him by his grandfather and how he survived, having even disbelieved the fact of his own survival. He broke down while commenting how we had forgotten the event in a flash, and were still ensconced in a similar situation a hundred years later.

After attending such a gloomy panel on a horrible chapter from our collective past, this scribe was ready for the riches offered by the panel on the literature of translation. Interestingly, at last 3 of the panelists had no formal experience with the art of translation (including the moderator) save Naveed Shahzad and Ruth Padel. Hanif, the English novelist worried about whether a Sindhi or Pashto writer could even reach him, since they were unlikely to be translated, therefore ways of supporting translators should be considered; Padel viewed translation as a tapestry which had a lot of colours but were all mixed up; Shahzad drew upon the experiences of her team in indigenizing the Shakespearian play The Taming of the Shrew and emphasized the cultural context to be translated. Shaista Sirajuddin enlightened with the more instructive remarks of the evening when she said that the English language itself was in the process of transformation; she highlighted this by citing two swear words from William Dalrymple’s latest work The Anarchy, which he said were very much part of the colonial discourse. The panel was well-served with examples from Nazim Hikmet’s translated poetry, as well as Catalan poetry and Padel’s own work.

This year the FIF offered a mixture of the ordinary and the extraordinary. When it began, the idea was to bind it to the socialist, secular and humanist ideals which were espoused by Pakistan’s resistance poet par excellence, Faiz Ahmad Faiz; the idea was also to distance it from what its more corporate litfest “rivals” in Lahore, Islamabad and Karachi were offering. It was a bit disheartening not to see the names of academics, activists, politicians and journalists who were barred from participating in last year’s FIF for this year’s edition. Many of the panels at this year’s FIF were clearly motivated by considerations of glamour, acceptability and corporate profit, such as the repetitive panels on mainstream politicians and the kowtowing to mainstream cinema. Despite the very welcome inclusion of three panels on translated books and translations at this year’s FIF, the disconnect between English and other Pakistani languages is still palpable at the FIF. Why couldn’t we, for example see a panel on Shaikh Ayaz or Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai at the FIF? Or a standalone panel on Saraiki literature and literature? 2020 marks the birth centenaries of two great stalwarts of Pakistan’s communist movement namely Abdullah Malik and Sobho Gianchandani, who were Punjabi and Sindhi, respectively, as well as the great but marginalized satirist Mohammad Khalid Akhtar; it also marks the 50th anniversary of the untimely death of the great Progressive poet Mustafa Zaidi, who attended university in Lahore.

Let the FIF mark these great anniversaries as a common link among the Punjabi, Sindhi and Urdu languages. Faiz would have wanted nothing less than that!

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

However one towering Punjabi writer and poet who was fortunate enough to be remembered on Day 1 of the FIF on her birth was Amrita Pritam. This was done by means of a tastefully-done dramatic rendition titled Men Tenun Fer Milaan Gi of the life and loves of Pritam by Sarmad Khoosat (as the poet Sahir Ludhianvi and then as Pritam’s artist-husband Imroz). Khoosat switched effortlessly between Pritam’s lover Sahir and her husband Imroz, now rendering Amrita’s heart-rending elegy to the ravaged daughters of the Punjab in the wake of the 1947 Partition Aj Aakhan Waris Shah Nun and Sahir’s equally moving poem on the hollow grandeur of the Taj Mahal; and then as the easel-loving Imroz. In fact, Nimra Bucha effortlessly held her own as the Punjabi doyenne with her luminous monologues and renderings of Pritam’s Punjabi poetry. It was noteworthy that the diction of the play was in Punjabi, given the Punjabi milieu and language of the three characters in the play. A minor quibble being that the play did not shed light on why Pritam walked out of an arranged marriage to her first husband; and secondly the play revolved too much around Pritam’s male protagonists Sahir and Imroz and insufficiently focused on the battles she fought against family and society to become the heroine of myth and legend that she became.

Amrita Pritam was remembered by means of a tastefully done dramatic rendition by Sarmad Khoosat of the life and loves of Pritam, titled “Men Tenun Fer Milaan Gi”

It was a dispiriting experience to walk in on a panel commemorating the three aforementioned Pakistani women writers right after such an uplifting drama on Pritam’s struggles and triumphs. Despite the fact that the panel commemorating three of our most distinguished writers - Altaf Fatima, Khalida Husain and Fahmida Riaz who all passed away last year – consisted of a senior critic Asif Farrukhi and distinguished panelists like Masood Ashar, Asghar Nadeem Syed and Dr Arfa Syeda Zehra, the discussion noted that though death brought the three writers closer to each other, each of them had an experience, training, style and ideology different to each other. The absence of two other important female writers, one each from Pakistan and India, Begum Perveen Atif (who also passed away last year) and Begum Masroor Jahan (who passed away earlier this year) on this panel was galling; perhaps their addition could have added something different and fresh to the panel, and saved it from a mere regurgitation of similar observations elsewhere. Also, Enver Sajjad, another towering Progressive writer who also passed away last year and ironically had a major role in creating the venue where the FIF was held, was particularly felt. Perhaps a better way to repeat this panel would have been to pay a dramatic tribute to the three departed writers as was the case with Amrita Pritam or to have a dramatic reading of one of the short-stories or extracts from these writers to give the audience a better idea of their work and worth.

Perhaps one of the best sessions on Day 1 of the FIF was the book launch of Prison Interlude by Zafarullah Poshni, the last living survivor of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case against the Liaquat Ali Khan government in 1951. It was heartening to note the presence of many young people in the session, thereby proving that there is yet life in this cautionary tale from a seemingly bygone era. The most riveting conversation was by noted columnist Babar Sattar who said that the book talks about an event which continues to be on repeat in Naya Pakistan, as governments were still creating military courts and not only did this come under the Official Secrets Act, but ordinary people were not allowed to attend proceedings; and the issue of the “class” of jail was still relevant in the case of the under-trial former prime ministers Nawaz Sharif and Shahid Khaqan Abbasi. He wryly added that the young people not aware of the incident in the age of mass media and marginalization in textbooks should not think that they had missed anything. The book launch marked a welcome emphasis on translations at the FIF, since translated works or a discussion on translation had been notoriously absent in preceding years. A minor miracle being that the author himself managed to translate his book into English at the age of 94, underscoring the value of translating other seminal Urdu reminiscences into English like Rauf Malik’s enlightening autobiography Surkh Siyasat and Major Ishaq’s book on the trial and murder of young communist Hasan Nasir in 1960 (the latter being one of the prominent accused in the 1951 Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case).

Another huge pleasant surprise was the panel on “Lahore: City of Literature”, organized after UNESCO’s recent announcement of that Pakistani city as one of its worldwide Cities of Literature. The panel featured the senior writer and poet Amjad Islam Amjad along with the Commissioner of Lahore and Amina Ali, who had done the homework leading to the aforementioned distinction for Lahore. Amjad charmingly kept the whole panel together by sharing amusing and instructive anecdotes about some of Lahore’s distinguished poets and writers like Ehsan Danish, Sahir Ludhianvi and Chiragh Hasan Hasrat. He lamented the loss of the tradition among Lahore’s writers of giving space to various ideological views, as well as the additional challenged of the expansion of Lahore and the recurrent smog.

Day 2 at the FIF began with a panel on the influence of Faiz on contemporary poetry, meaning the poetry of what are usually deemed “regional” languages. Dr Ishaq Samejo said that the great Sindhi poet Shaikh Ayaz learned from Faiz and some of his best political poetry was written in jail, like the latter; Sadia Kamal arrived late for her panel and spent more time in talking about Seraiki resistance poetry in general than the topic of the panel; Fatima Hasan noted how close Sheikh Ayaz and Fahmida Riaz were to Faiz in their style, she herself started writing under the influence of Faiz; Allah Baksh Bozdar talked about how three generations of Balochis called Faiz a wali, and how Faiz and Jalib were among a handful of Punjabis who the Baloch loved; Ahmad Salim, the noted Punjabi poet talked about he himself had learnt about Heer Waris Sah and Amrita Pritam from Faiz and also lamented that had Faiz written a few more Punjabi poems in addition to the 6-7 poems he had written, his place in Punjabi letters would have been assured; noted human rights activist and left-wing Pakhtun politician Afrasiab Khattak talked about how Faiz was a champion of diversity and did not want to see the Urdu language ensconced in Pakistan by force.

It was a bit disheartening not to see the names of academics, activists, politicians and journalists who were barred from participating in last year’s FIF for this year’s edition

Mohammed Hanif has of late been a fixture at literary festivals both in Pakistan and abroad, and a regular at the FIF. This time he talked with lawyer and novelist Osama Siddique about the recent Urdu translation of his novel A Case of Exploding Mangoes by KJashif Raza. His hilarious description of the whole process of how the novel eventually came to be translated after seven long years, and his travails after being rejected by a major publisher from Lahore were instructive. He also talked about his own fresh take on resistance poetry, “from resistance, you can’t have a lousy poem”, case in point being Barrister Aitzaz Ahsan’s poem Kal, Aaj aur Kal, which became an anthem for the anti-Musharraf Lawyers’ Movement. He was surprisingly less forthcoming when asked to offer by way of advice about writers who had inspired him and what young people should read today, perhaps betraying his lack of knowledge about what is being published even in Urdu (apart from what his friends’ write) and other Pakistani languages. The conversation with Hanif was similar in scope as was his conversation with Harris Khalique last year at FIF; perhaps since Hanif has been a journalist for much longer before than he became a novelist, he should have been utilized for the panels on media and journalism like the ones on “Using Media to Address Social Issues”, “Aaj ke Daur Men Inqalabi Sahafat” and “Digital Media in Pakistan” at this year’s FIF. When the same writers are invited repeatedly every year, even their humour gets stale! On the contrary, there have been several capable, emerging writers who have written debut or new novels in English, like Haroon Khalid and Uzma Aslam Khan who could have provided the audience with some refreshing insights about English fiction writing in Pakistan.

Zehra Nigah missed out on the last FIF due to ill health and her panel was duly conducted by Dr Arfa Zehra. However this year in a panel again featuring the latter and moderated by Qasim Jafri, Nigah talked about the genres of poetry. The moderator and in turn the panelists wisely decided to leave the remaining 31 genres of poetry alone and talk about only 3-4 aspects namely ghazal, nazm, marsiya and qasida. When prompted by Jafri as to the greatest poets among the 1,000 poets who were published, the panelists agreed on Mir, Ghalib and Iqbal. The often-times boring, academic discussion was regaled by recitations from the marsiyas of Josh and Mir Anees.

2019 also marks the centennial of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in Amritsar in April 1919 and as such there was a panel on it at the FIF. It was interesting to note the presence of Punjabi poet and industrial management academic Arvinder Chamak from Amritsar, whose grandfather was survivor of the massacre. The panel began by noting that the massacre represented the fact that violence was central to colonialism; that Punjabi anti-British agitation in the wake of the massacre gave the lie to claims of the Punjabis always being collaborators with outsiders. Chamak very movingly spoke about the gory details of the Massacre as handed down to him by his grandfather and how he survived, having even disbelieved the fact of his own survival. He broke down while commenting how we had forgotten the event in a flash, and were still ensconced in a similar situation a hundred years later.

After attending such a gloomy panel on a horrible chapter from our collective past, this scribe was ready for the riches offered by the panel on the literature of translation. Interestingly, at last 3 of the panelists had no formal experience with the art of translation (including the moderator) save Naveed Shahzad and Ruth Padel. Hanif, the English novelist worried about whether a Sindhi or Pashto writer could even reach him, since they were unlikely to be translated, therefore ways of supporting translators should be considered; Padel viewed translation as a tapestry which had a lot of colours but were all mixed up; Shahzad drew upon the experiences of her team in indigenizing the Shakespearian play The Taming of the Shrew and emphasized the cultural context to be translated. Shaista Sirajuddin enlightened with the more instructive remarks of the evening when she said that the English language itself was in the process of transformation; she highlighted this by citing two swear words from William Dalrymple’s latest work The Anarchy, which he said were very much part of the colonial discourse. The panel was well-served with examples from Nazim Hikmet’s translated poetry, as well as Catalan poetry and Padel’s own work.

This year the FIF offered a mixture of the ordinary and the extraordinary. When it began, the idea was to bind it to the socialist, secular and humanist ideals which were espoused by Pakistan’s resistance poet par excellence, Faiz Ahmad Faiz; the idea was also to distance it from what its more corporate litfest “rivals” in Lahore, Islamabad and Karachi were offering. It was a bit disheartening not to see the names of academics, activists, politicians and journalists who were barred from participating in last year’s FIF for this year’s edition. Many of the panels at this year’s FIF were clearly motivated by considerations of glamour, acceptability and corporate profit, such as the repetitive panels on mainstream politicians and the kowtowing to mainstream cinema. Despite the very welcome inclusion of three panels on translated books and translations at this year’s FIF, the disconnect between English and other Pakistani languages is still palpable at the FIF. Why couldn’t we, for example see a panel on Shaikh Ayaz or Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai at the FIF? Or a standalone panel on Saraiki literature and literature? 2020 marks the birth centenaries of two great stalwarts of Pakistan’s communist movement namely Abdullah Malik and Sobho Gianchandani, who were Punjabi and Sindhi, respectively, as well as the great but marginalized satirist Mohammad Khalid Akhtar; it also marks the 50th anniversary of the untimely death of the great Progressive poet Mustafa Zaidi, who attended university in Lahore.

Let the FIF mark these great anniversaries as a common link among the Punjabi, Sindhi and Urdu languages. Faiz would have wanted nothing less than that!

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com