Some political minds, such as Senator Farhatullah Babar, would argue that Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif was the second casualty of the Panama Papers, and that the first one was, in fact, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) merger proposal. Such, it seems, was the view, at least, at a seminar organised recently by the Shaheed Bhutto Foundation around the theme of “Delaying Fata reforms”.

The Shaheed Bhutto Foundation was established with approval from the late Benazir Bhutto in 2005 when she was at Dubai. The Foundation has arranged a process of dialogue on what is seen by many analysts as an extra-constitutional status quo in Fata. The inhabitants of Fata are still living under draconian British colonial regulations, the 1901 Frontier Crimes Regulations. To sum up that status quo, there is effectively no judiciary, police system or constitutional protection – at least as Pakistanis in other parts of the country know it – for Fata. It ought to come as little surprise, then, that the FCR is now seen as a stigma by many people in this area.

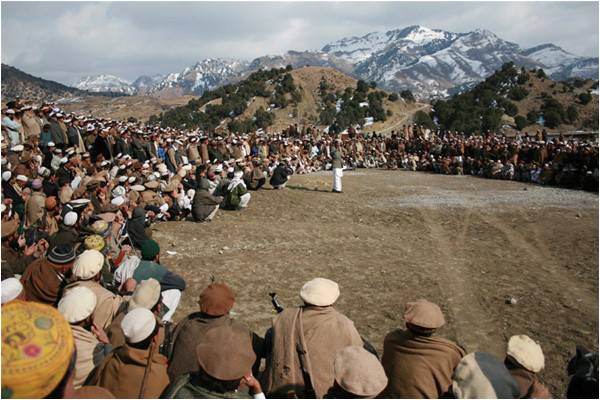

In recent years, there has been an exodus of tribal populations from their hometowns in a part of Pakistan where the constitution does not apply as it does elsewhere to the more ‘constitutional’ parts of Pakistan. This was mostly due militancy in the region – and later the state’s inevitable, fierce response. The deprived and isolated tribal people, during this exodus, witnessed their more prosperous and liberated brethren in Peshawar, Islamabad and other large cities. Quite understandably, disgruntlement about the FCR grew. Meanwhile, in Fata itself, elders and notables (maliks) who were perceived as being pro-Establishment forces were perfecting a peculiar old narrative which owes much of its origins to the British colonialists – one of “Azad Qabail” (Free Tribes). Such a notion was, of course, calculatedly deployed to appeal to the narcissism of at least some parts of the population – so much that they even protested in the past against the Awami National Party (ANP) and its resolution in favour of a merger between Fata and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the provincial assembly.

The cabinet approved the Fata Reforms Committee recommendations and appeared receptive. The security establishment appeared to acquiesce. The KP government, including opposition parties, seemed ready. And yet, the reforms ended up delayed. Why?

Legislator and Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) stalwart Senator Farhatullah Babar asks the same question.

And then, in a packed hall, at the Foundation’s seminar, Babar himself breaks the silence and answers the question.

There were both visible and invisible roadblocks holding up the Fata reforms, Babar believes. Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman and Mehmood Khan Achakzai were the visible hurdles, according to him. And the invisible hurdle, he believes, was the bureaucracy: both the civil and military components of the state. In the beginning, we are told, the civil bureaucracy favoured the changes but eventually they opposed the merger plan.

The sitting government of the PML-N formed a committee, which forwarded its recommendations after consultative meetings with stakeholders of various views. In the end, the PML-N didn’t accept those points. This did, of course, fly in the face of the PML-N’s own previous commitments to the people of Fata.

The Panama Papers became a relevant factor in delaying reforms because at that time the PML-N leadership was under immense pressure and was looking for strong parliamentary backing. Nawaz Sharif was hoping for the same support from mainstream parties as he was able to marshal during the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) sit-in at the capital in 2014.

Meanwhile, in Fata, there had been optimism. People felt the stage was set to approve the merger bill and make Fata a part of KP. Some parliamentarians from Fata even distributed mithai, while celebratory functions were planned across the Agencies of the tribal region.

Then, politicians Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman of the JUI-F and Mehmood Khan Achakzai of the PkMAP appeared on the scene, in full-blown opposition to the merger. Nawaz Sharif was in China, but he informed PML-N stalwarts that for now the Fata merger bill had to be scuttled.

“History was in the making but the PML-N is not lucky enough to be part of it – and doesn’t have the guts to do so!” Babar says as he lambasts his party’s traditional rivals in government.

As leaders of a Pashtun background themselves, both Fazl-ur-Rehman and Achakzai threatened to leave the governing coalition, if the PML-N leadership approved the bill.

Mian Iftikhar Hussain, an ANP stalwart and champion of the merger, is livid at what he considers a betrayal of Pashtun interests:

“One (Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman) is working to bring all the Muslim ummah under one flag but on the other hand he has vowed to counter Fata Muslims’ integration with their KP brothers!” As for the other figure, “‘Da Chitrala tar Bolana, Pukhtana yaw ka Mehmood Khana!’ [From Chitral to Bolan, unite the Pashtuns, Mehmood Khan!] is the slogan of Achakzai’s followers, but at the time of the merger he took a U-turn and sat in the opposite camp!”

Journalist Rasool Dawar agrees. “I couldn’t imagine what reason one could have for supporting the pro-FCR stance, as Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman and the JUI-F have done!” Dawar comes from Waziristan.

He believes that the JUI-F have taken such a stance at the peril of the party’s political future. According to Dawar, the JUI-F have made two blunders. One is their support of what is popularly seen as a punitive British colonial law. The other is that when the people of Waziristan were living in camps in settled areas, the Maulana’s party was not seen to be helpful enough towards the displaced people.

Shahida Shah, an activist, takes issue with the discourse around ‘Azad Qabail’ and the related notions of ‘ghairat’ (honour) that have been invoked by supporters of the FCR. She believes that the opportunity to live with (relatively) modern education, health, policing and judicial systems astonished the tribal refugees who moved to other parts of Pakistan. “The tribal now understood what is real freedom and saw first-hand the respect that is due to a citizen,” she says. The conservative and patriarchal status quo that goes with the ‘Azad Qabail’ rhetoric is not appreciated as widely as pro-FCR leaders would claim. In fact, Shah believes that her fellow women of the tribal areas are the foremost victims of the chaos and violence of the past decade or so. The impetus for change, as represented by the demands for merging Fata with KP, is for her, first and foremost a women’s issue too.

ANP leaders fear that with the strengthening of the Pakistani state’s posture of ‘strategic depth’ in Afghanistan, especially in light of US President Trump’s muscular policy in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the forces preserving the political and constitutional status quo in Fata will only be strengthened.

For JUI-F version, I speak on the phone with party leader Munir Orakzai. He says: “We don’t support FCR nor do we favour an immediate merger. Our party’s stand is clear: we want first mainstreaming and reforms and then a referendum to make the process inclusive for the residents of the area.”

Former KP governor Barrister Masood Kausar speaks at the seminar too, recounting his own experiences of the difficulty in dealing with corruption in Fata. One one occasion, he says: “I asked the officials to brief me on the ongoing developmental projects of Orakzai Agency – on the ground and not in Governor House. On that very day as my helicopter landed, a huge blast occurred and even a rocket was fired near the spot where I supposed to meet the officers.”

He says the war-torn region urgently needs to be included in the Pakistani political and legal process that is applied in the rest of the country.

Raheem Shah Afridi, president of the Fata Lawyers Forum, informs the people at the seminar that the country’s ruling establishment now seeks to promulgate the Rewaj Act, which in his opinion is in many ways a duplicate of the FCR.

Inevitably, the security policy of the state comes under criticism as frustration mounts over the scuttling of the merger. Senator Farhatullah Babar minces few words in dishing out such criticism.

He emphasises that until a few months ago, many power-centres of the country seemed willing to countenance the merger of Fata in KP province. At the eleventh hour, the merger was halted and the idea of ‘mainstreaming’ Fata was brought in. “What is mainstreaming? Are we not in the mainstream of Pakistan?” some student leaders from Fata ask. They take exception to the idea that there is still some more proof required of the people of Fata that they are worthy of inclusion.

Outrage over what is seen as a paternalistic attitude towards them is further increased by the fact that the popular self-image of Fata’s people is that they are intensely patriotic Pakistanis.

Rasool Dawar, at least, is of the opinion that in future elections, assuming them to be free and fair, those who have opposed the merger would pay a heavy political and electoral price in terms of votes lost.

Farhatullah Babar and the PPP would be eager to step into any political space thus created. He believes the PPP government from 2008 to 2013 defied the power centres which support the status quo in Fata. The Fata merger, as far as Babar is concerned, awaits a PPP government.

One imagines that the significant mass of people in Fata who supported a merger will have to find ways to reconcile themselves, for the foreseeable future, to the bitter political, strategic and historical realities of their region.

The writer can be reached at journalist.rauf@gmail.com and tweets at @theraufkhan

The Shaheed Bhutto Foundation was established with approval from the late Benazir Bhutto in 2005 when she was at Dubai. The Foundation has arranged a process of dialogue on what is seen by many analysts as an extra-constitutional status quo in Fata. The inhabitants of Fata are still living under draconian British colonial regulations, the 1901 Frontier Crimes Regulations. To sum up that status quo, there is effectively no judiciary, police system or constitutional protection – at least as Pakistanis in other parts of the country know it – for Fata. It ought to come as little surprise, then, that the FCR is now seen as a stigma by many people in this area.

Shahida Shah, a social activist, takes issue with the discourse around 'Azad Qabail' (Free Tribes) and the related notions of 'ghairat' (honour) that have been invoked by supporters of the FCR

In recent years, there has been an exodus of tribal populations from their hometowns in a part of Pakistan where the constitution does not apply as it does elsewhere to the more ‘constitutional’ parts of Pakistan. This was mostly due militancy in the region – and later the state’s inevitable, fierce response. The deprived and isolated tribal people, during this exodus, witnessed their more prosperous and liberated brethren in Peshawar, Islamabad and other large cities. Quite understandably, disgruntlement about the FCR grew. Meanwhile, in Fata itself, elders and notables (maliks) who were perceived as being pro-Establishment forces were perfecting a peculiar old narrative which owes much of its origins to the British colonialists – one of “Azad Qabail” (Free Tribes). Such a notion was, of course, calculatedly deployed to appeal to the narcissism of at least some parts of the population – so much that they even protested in the past against the Awami National Party (ANP) and its resolution in favour of a merger between Fata and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the provincial assembly.

The cabinet approved the Fata Reforms Committee recommendations and appeared receptive. The security establishment appeared to acquiesce. The KP government, including opposition parties, seemed ready. And yet, the reforms ended up delayed. Why?

Legislator and Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) stalwart Senator Farhatullah Babar asks the same question.

And then, in a packed hall, at the Foundation’s seminar, Babar himself breaks the silence and answers the question.

There were both visible and invisible roadblocks holding up the Fata reforms, Babar believes. Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman and Mehmood Khan Achakzai were the visible hurdles, according to him. And the invisible hurdle, he believes, was the bureaucracy: both the civil and military components of the state. In the beginning, we are told, the civil bureaucracy favoured the changes but eventually they opposed the merger plan.

Politicians Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman of the JUI-F and Mehmood Khan Achakzai of the PkMAP appeared on the scene, in full-blown opposition to the merger. Nawaz Sharif was in China, but he informed PML-N stalwarts that for now the Fata merger bill had to be scuttled

The sitting government of the PML-N formed a committee, which forwarded its recommendations after consultative meetings with stakeholders of various views. In the end, the PML-N didn’t accept those points. This did, of course, fly in the face of the PML-N’s own previous commitments to the people of Fata.

The Panama Papers became a relevant factor in delaying reforms because at that time the PML-N leadership was under immense pressure and was looking for strong parliamentary backing. Nawaz Sharif was hoping for the same support from mainstream parties as he was able to marshal during the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) sit-in at the capital in 2014.

Meanwhile, in Fata, there had been optimism. People felt the stage was set to approve the merger bill and make Fata a part of KP. Some parliamentarians from Fata even distributed mithai, while celebratory functions were planned across the Agencies of the tribal region.

Then, politicians Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman of the JUI-F and Mehmood Khan Achakzai of the PkMAP appeared on the scene, in full-blown opposition to the merger. Nawaz Sharif was in China, but he informed PML-N stalwarts that for now the Fata merger bill had to be scuttled.

“History was in the making but the PML-N is not lucky enough to be part of it – and doesn’t have the guts to do so!” Babar says as he lambasts his party’s traditional rivals in government.

As leaders of a Pashtun background themselves, both Fazl-ur-Rehman and Achakzai threatened to leave the governing coalition, if the PML-N leadership approved the bill.

Mian Iftikhar Hussain, an ANP stalwart and champion of the merger, is livid at what he considers a betrayal of Pashtun interests:

“One (Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman) is working to bring all the Muslim ummah under one flag but on the other hand he has vowed to counter Fata Muslims’ integration with their KP brothers!” As for the other figure, “‘Da Chitrala tar Bolana, Pukhtana yaw ka Mehmood Khana!’ [From Chitral to Bolan, unite the Pashtuns, Mehmood Khan!] is the slogan of Achakzai’s followers, but at the time of the merger he took a U-turn and sat in the opposite camp!”

Journalist Rasool Dawar agrees. “I couldn’t imagine what reason one could have for supporting the pro-FCR stance, as Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman and the JUI-F have done!” Dawar comes from Waziristan.

He believes that the JUI-F have taken such a stance at the peril of the party’s political future. According to Dawar, the JUI-F have made two blunders. One is their support of what is popularly seen as a punitive British colonial law. The other is that when the people of Waziristan were living in camps in settled areas, the Maulana’s party was not seen to be helpful enough towards the displaced people.

Shahida Shah, an activist, takes issue with the discourse around ‘Azad Qabail’ and the related notions of ‘ghairat’ (honour) that have been invoked by supporters of the FCR. She believes that the opportunity to live with (relatively) modern education, health, policing and judicial systems astonished the tribal refugees who moved to other parts of Pakistan. “The tribal now understood what is real freedom and saw first-hand the respect that is due to a citizen,” she says. The conservative and patriarchal status quo that goes with the ‘Azad Qabail’ rhetoric is not appreciated as widely as pro-FCR leaders would claim. In fact, Shah believes that her fellow women of the tribal areas are the foremost victims of the chaos and violence of the past decade or so. The impetus for change, as represented by the demands for merging Fata with KP, is for her, first and foremost a women’s issue too.

ANP leaders fear that with the strengthening of the Pakistani state’s posture of ‘strategic depth’ in Afghanistan, especially in light of US President Trump’s muscular policy in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the forces preserving the political and constitutional status quo in Fata will only be strengthened.

For JUI-F version, I speak on the phone with party leader Munir Orakzai. He says: “We don’t support FCR nor do we favour an immediate merger. Our party’s stand is clear: we want first mainstreaming and reforms and then a referendum to make the process inclusive for the residents of the area.”

Former KP governor Barrister Masood Kausar speaks at the seminar too, recounting his own experiences of the difficulty in dealing with corruption in Fata. One one occasion, he says: “I asked the officials to brief me on the ongoing developmental projects of Orakzai Agency – on the ground and not in Governor House. On that very day as my helicopter landed, a huge blast occurred and even a rocket was fired near the spot where I supposed to meet the officers.”

He says the war-torn region urgently needs to be included in the Pakistani political and legal process that is applied in the rest of the country.

Raheem Shah Afridi, president of the Fata Lawyers Forum, informs the people at the seminar that the country’s ruling establishment now seeks to promulgate the Rewaj Act, which in his opinion is in many ways a duplicate of the FCR.

Inevitably, the security policy of the state comes under criticism as frustration mounts over the scuttling of the merger. Senator Farhatullah Babar minces few words in dishing out such criticism.

He emphasises that until a few months ago, many power-centres of the country seemed willing to countenance the merger of Fata in KP province. At the eleventh hour, the merger was halted and the idea of ‘mainstreaming’ Fata was brought in. “What is mainstreaming? Are we not in the mainstream of Pakistan?” some student leaders from Fata ask. They take exception to the idea that there is still some more proof required of the people of Fata that they are worthy of inclusion.

Outrage over what is seen as a paternalistic attitude towards them is further increased by the fact that the popular self-image of Fata’s people is that they are intensely patriotic Pakistanis.

Rasool Dawar, at least, is of the opinion that in future elections, assuming them to be free and fair, those who have opposed the merger would pay a heavy political and electoral price in terms of votes lost.

Farhatullah Babar and the PPP would be eager to step into any political space thus created. He believes the PPP government from 2008 to 2013 defied the power centres which support the status quo in Fata. The Fata merger, as far as Babar is concerned, awaits a PPP government.

One imagines that the significant mass of people in Fata who supported a merger will have to find ways to reconcile themselves, for the foreseeable future, to the bitter political, strategic and historical realities of their region.

The writer can be reached at journalist.rauf@gmail.com and tweets at @theraufkhan