Muhammed Ali Jinnah, popularly known as Quaid-e-Azam, remains an enigmatic figure of the Indo-Pak freedom movement. He continues to draw the attention of those still seeking answers to complex pre-Partition questions.

How did he achieve what once looked unachievable? Was it really possible through mere political manoeuvring?

Jinnah is still lauded for creating a separate homeland for Muslims and derided for dividing a land into two. Why he played these contradicting roles, upholding contrasting schools of thought, is a question that has polarised historians. Some define Jinnah as a separatist others as a nationalist.

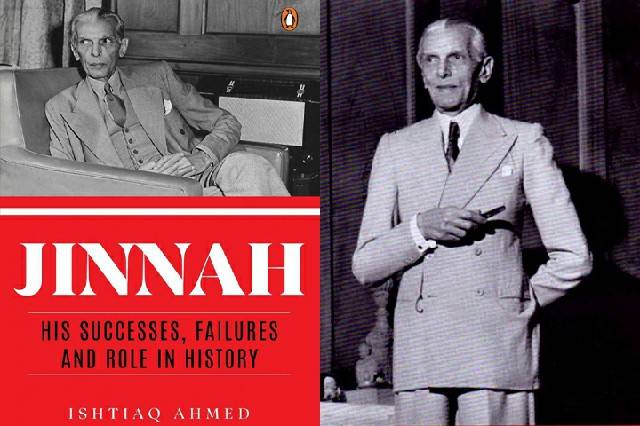

A new book, ‘Jinnah: His Success, Failures and Role in History’, written by prolific writer Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed, attempts to answer these burning questions.

Dr Ishtiaq’s objectivity in research supersedes his ideological beliefs, which eventually benefits the readers with the variety of information that his books offer. The book unveils events and the political environments where Jinnah had to struggle, eventually making a choice between two historical roles: to be an Indian nationalist or a communitarian, a secularist or a fundamentalist. The book chronicles the circumstances that gave rise to Jinnah’s unchallengeable authority and forced him to alter his stances in accordance with the demands of the situation.

Dr Ishtiaq’s narrative questions previous perceptions on Jinnah. The author underlines that it was Jinnah’s own conviction and not the policies of Congress that made him pick separatism over nationalism. With historical references, Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed highlights that with the exception of a few initial stances, Jinnah was always more inclined towards separatism than his adversaries. However, the author doesn’t shy away from delineating the behaviour of Mahatma Gandhi, who quite often carried a subtle touch of indecency towards Jinnah.

The author has meticulously gone through scores of documents to establish how Jinnah used the religious card. The book not only unveils the deep influences of religion in the polity of Indian society, but also identifies it as a source of differences between Hindu and Muslim communities. The author traces it to the pioneer of the Muslim enlightenment, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, and his objection to the recruitment of the Muslim and Hindu soldiers in the same army.

Once Jinnah embarked upon his journey as a communal leader, the use of religion and religious identities became frequent as he argued in favour of the Two-Nation Theory. Whether dealing with economic woes or demanding political rights, religion remained the focus.

The economic considerations that led Muslims of Punjab and Bengal to seek solutions that suited their own provincial interests, and not the broader interests of Indian Muslims, make an interesting read. The Muslims of the two provinces to abandoned their Muslim brethren to the mercy of Hindu majoritarian rule, which they were rallying against. Jinnah had to accept this ground reality and announced that in order to liberate seven crores of Muslims where they were in majority, he was willing to “perform the last ceremony of martyrdom if necessary” and let two crores of Muslims be smashed.

Jinnah’s brilliance in turning his rivals’ mistakes into opportunities has lessons for political science students. The book reveals how this helped Jinnah build on the Two Nation Theory, even going as far as denouncing democracy, the edifice of the British political system. What led Jinnah to take this position is vividly covered in the book. Referring to a letter of Lala Lajpat Rai of Hindu Mahasabha, Jinnah is quoted as saying, “….although we (Hindu-Muslim communities) can unite against the British we cannot do so to rule Hindustan on British lines. We cannot do so to rule Hindustan on democratic lines.”

Despite being a minority leader, Jinnah, with his political insight and nous, often put the majority party into a situation where no solution was easily adoptable for them. During the Simla Conference in 1945, Jinnah demanded that no Muslim be nominated by the Congress for the Executive Council responsible for making India’s Constitution. With Abul Kalam Azad in the presidential seat, compliance would’ve reduced Congress to a communal party, while noncompliance was bound to impact the power transfer process. Jinnah’s inflexibility eventually pushed Congress into including all Hindu members for interim government formation.

Winning the 1946 election from the Muslim dominated provinces was the tipping point for Jinnah’s demand for Partition. August 16, 1946 was the first time the Muslim League observed a peaceful strike as a part of their Direct Action Day plan, while later turned into a four-day spree of communal violence in Calcutta.

On Jinnah’s ostensible ideological contradictions, especially in light of his famous August 11, 1947 speech upholding secular ideas, Dr Ishtiaq offers an unconventional explanation: it was Jinnah’s attempt to convince the international community that Pakistan would adopt inclusive policies and to dissuade India from forcing mass migration of Indian Muslims, which could’ve created an existential crisis. As Jinnah didn’t pursue his August 11 ideals afterward, Dr Ishtiaq believes it wasn’t anything more than a political strategy.

I believe the August 11 speech was Jinnah’s second failed attempt — the first coming during his time as a Congress leader — to find buyers of his secular ideas, which were refuted by both the Congress and the Muslim League. And after flaring up religious sentiments, it was no longer possible for Jinnah to revert to his old ideals.

Whether Jinnah was a fundamentalist or a secularist is not as important as the results he achieved from his political policies. And Dr Ishtiaq’s book provides ample details to provide readers, analysts, and activists, new orientations to look at Jinnah from.

How did he achieve what once looked unachievable? Was it really possible through mere political manoeuvring?

Jinnah is still lauded for creating a separate homeland for Muslims and derided for dividing a land into two. Why he played these contradicting roles, upholding contrasting schools of thought, is a question that has polarised historians. Some define Jinnah as a separatist others as a nationalist.

A new book, ‘Jinnah: His Success, Failures and Role in History’, written by prolific writer Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed, attempts to answer these burning questions.

Dr Ishtiaq’s objectivity in research supersedes his ideological beliefs, which eventually benefits the readers with the variety of information that his books offer. The book unveils events and the political environments where Jinnah had to struggle, eventually making a choice between two historical roles: to be an Indian nationalist or a communitarian, a secularist or a fundamentalist. The book chronicles the circumstances that gave rise to Jinnah’s unchallengeable authority and forced him to alter his stances in accordance with the demands of the situation.

The use of religion became frequent as Jinnah argued in favour of the Two-Nation Theory. Whether dealing with economic woes or demanding political rights, religion remained the focus

Dr Ishtiaq’s narrative questions previous perceptions on Jinnah. The author underlines that it was Jinnah’s own conviction and not the policies of Congress that made him pick separatism over nationalism. With historical references, Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed highlights that with the exception of a few initial stances, Jinnah was always more inclined towards separatism than his adversaries. However, the author doesn’t shy away from delineating the behaviour of Mahatma Gandhi, who quite often carried a subtle touch of indecency towards Jinnah.

The author has meticulously gone through scores of documents to establish how Jinnah used the religious card. The book not only unveils the deep influences of religion in the polity of Indian society, but also identifies it as a source of differences between Hindu and Muslim communities. The author traces it to the pioneer of the Muslim enlightenment, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, and his objection to the recruitment of the Muslim and Hindu soldiers in the same army.

Once Jinnah embarked upon his journey as a communal leader, the use of religion and religious identities became frequent as he argued in favour of the Two-Nation Theory. Whether dealing with economic woes or demanding political rights, religion remained the focus.

The economic considerations that led Muslims of Punjab and Bengal to seek solutions that suited their own provincial interests, and not the broader interests of Indian Muslims, make an interesting read. The Muslims of the two provinces to abandoned their Muslim brethren to the mercy of Hindu majoritarian rule, which they were rallying against. Jinnah had to accept this ground reality and announced that in order to liberate seven crores of Muslims where they were in majority, he was willing to “perform the last ceremony of martyrdom if necessary” and let two crores of Muslims be smashed.

Jinnah’s brilliance in turning his rivals’ mistakes into opportunities has lessons for political science students. The book reveals how this helped Jinnah build on the Two Nation Theory, even going as far as denouncing democracy, the edifice of the British political system. What led Jinnah to take this position is vividly covered in the book. Referring to a letter of Lala Lajpat Rai of Hindu Mahasabha, Jinnah is quoted as saying, “….although we (Hindu-Muslim communities) can unite against the British we cannot do so to rule Hindustan on British lines. We cannot do so to rule Hindustan on democratic lines.”

Despite being a minority leader, Jinnah, with his political insight and nous, often put the majority party into a situation where no solution was easily adoptable for them. During the Simla Conference in 1945, Jinnah demanded that no Muslim be nominated by the Congress for the Executive Council responsible for making India’s Constitution. With Abul Kalam Azad in the presidential seat, compliance would’ve reduced Congress to a communal party, while noncompliance was bound to impact the power transfer process. Jinnah’s inflexibility eventually pushed Congress into including all Hindu members for interim government formation.

Jinnah’s brilliance in turning his rivals’ mistakes into opportunities has lessons for political science students. Despite being a minority leader, he often put the majority party into a situation where no solution was easily adoptable for them.

Winning the 1946 election from the Muslim dominated provinces was the tipping point for Jinnah’s demand for Partition. August 16, 1946 was the first time the Muslim League observed a peaceful strike as a part of their Direct Action Day plan, while later turned into a four-day spree of communal violence in Calcutta.

On Jinnah’s ostensible ideological contradictions, especially in light of his famous August 11, 1947 speech upholding secular ideas, Dr Ishtiaq offers an unconventional explanation: it was Jinnah’s attempt to convince the international community that Pakistan would adopt inclusive policies and to dissuade India from forcing mass migration of Indian Muslims, which could’ve created an existential crisis. As Jinnah didn’t pursue his August 11 ideals afterward, Dr Ishtiaq believes it wasn’t anything more than a political strategy.

I believe the August 11 speech was Jinnah’s second failed attempt — the first coming during his time as a Congress leader — to find buyers of his secular ideas, which were refuted by both the Congress and the Muslim League. And after flaring up religious sentiments, it was no longer possible for Jinnah to revert to his old ideals.

Whether Jinnah was a fundamentalist or a secularist is not as important as the results he achieved from his political policies. And Dr Ishtiaq’s book provides ample details to provide readers, analysts, and activists, new orientations to look at Jinnah from.